Having researched the International Relations curriculum at the London School of Economics as part of a student-led project on gender bias in reading lists, Gustav Meibauer and Kiran Phull make the case that course syllabi present an oft-overlooked primary source of research in higher education.

Syllabi are (also) data. Much is to be gained from treating them as such.

Of course, for students they provide instructions as to what to do and how to perform in a specific course. For instructors, they are often the product of considerable labour, scholarly expertise, and administrative effort. For the university, they provide the black-on-white skeleton of the curriculum and a means of standardising administration across courses. As Christy Wampole writes, syllabi are “the interface between the institution, the instructor and the student”. And yet, they are still frequently treated as a by-product of the curriculum and pedagogy, a necessary but theoretically uninteresting inventory of procedures, practices, and recommended readings in higher education (HE). This view, however, fails to account for the full value of syllabi as research tools. Beyond the bounds of their administrative functions, syllabi serve as a form of data—as valuable information that can be used in the qualitative and quantitative analysis of critical pedagogical questions about the curriculum. And crucially, understanding syllabi as data allows us to build a more reflexive agenda around issues of knowledge (re)production, positionality, and the everyday practices of higher education teaching and learning.

The syllabus (de)constructed

A syllabus conventionally distils the core information of a course into a single document. It seeks to represent, for specific subject matter and from the perspective of its creator, the state-of-the-art in terms of scholarship and literature. It focuses on what will be taught and learned – how, when, and measured against which benchmarks. It includes practical details (the instructor’s name, office hours, etc.), a synopsis of the course content, the institutionalised expectations, rules and regulations regarding assessment and grading, a structured rundown of how lectures and seminars will thematically proceed, and a reading list with key texts and other supporting resources meant to accompany the course and reflect its intellectual aims.

The incredible wealth of information embedded in syllabi, assembled by one or more instructors, administrators and seminar tutors, often rewritten and refined over multiple years, and at times even passed down through generations of scholars and departments (what Wampole calls “a kind of composting process, a vegetal reworking of the old into the new”), opens a plethora of possibilities for asking both disciplinary-specific as well as wider pedagogical, historical, and social questions. The Open Syllabus Project, which maps out millions of class syllabi across the globe, is an astounding example of this potential.

A proxy for disciplinary trends

Notably, a syllabus is, in its own way, a scholarly product, and therefore should invite similar analytical scrutiny as any other scholarly work. This means that the syllabus, as a scholarly artefact, leads directly to questions about disciplinarity, curricula, and the “canon” i.e. the institutionalised embodiment of the imaginary mainstream discipline. Syllabi as data allow us to probe which ideas and voices are considered essential to the study of a discipline and trace how these have changed over time. They can tell us which subjects and methods are repeatedly reinforced and which ones fall off the radar. They can be used to help construct histories of our taught disciplines. They can also tell us how disciplinary expectations differ across countries.

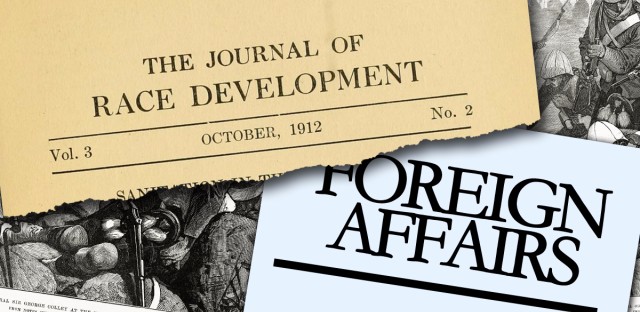

Foreign Affairs was once known as the Journal of Race Development*

Foreign Affairs was once known as the Journal of Race Development*

Studying syllabi may be particularly interesting in disciplines such as our own, International Relations (IR), where research on the politics of global knowledge production is breaking new ground. In recent history, universities like the LSE offered courses on imperial administration, and colonial administration was considered a disciplinary subfield of the study of Politics (recall that Foreign Affairs was once The Journal of Race Development). The curriculum in general, as well as syllabi, are likely to reflect the ebb and flow of history and disciplinary debates and trends, if perhaps with some delay—for example the decline in “Soviet Studies” degrees, the increase in terrorism-related courses, or the gradual advancement of gender studies across the social sciences. Even short-lived but critical historical junctures can shape curricula, as in the case of the spike of courses on the “Occupy” and other social movements in the United States circa 2012. The Occupy movement itself as a symbol of social justice extended into syllabi production when UC Berkeley’s “Occupy the Syllabus” movement challenged the stagnant and unreflective perspectives that students were required to learn in their curricula. Institutions, scholars, and student activists continue to challenge how we think about syllabi production and use. In this way, treating syllabi as data offers pathways to thinking critically about pedagogical improvement, for example towards a decolonised curriculum, if there can be such a thing.

Institutions, scholars, and student activists continue to challenge how we think about syllabi production and use. In this way, treating syllabi as data offers pathways to thinking critically about pedagogical improvement ...

Syllabi as data

Comparing syllabi across time also allows a glimpse into the history and historical practices of higher education more broadly. Consider not only the content of courses offered over time, but also the changing ways through which knowledge is framed and what this framing tells us about the academic landscape i.e. the hierarchical relationship between instructor and student, dominant pedagogical methods and teaching practices, or the changing nature of the classroom (such as the increase in the number of students numbers over time). How have expectations of learning changed? Are students treated as passive or active bodies? Does the traditional lecture format slowly fade to make room for interactive modalities of learning? How have digital technologies influenced how syllabi (and their associated knowledges) are produced and consumed, or how courses are designed, delivered and assessed? Even the language of syllabi can be laden with interesting and ever-changing power dynamics. Here again, syllabi can serve as an invaluable data-driven resource and reflexive directory for scholarship on teaching and learning.

Further, syllabi can be used to bridge disciplinary and pedagogical scholarship. In a recent study, for example, we investigated to what extent IR reading lists showed evidence of gender bias in terms of the inclusion of female-authored texts. With the help of LSE’s research librarians and as part of a larger, students-as-activists initiative, we assessed the entirety of the LSE’s IR curriculum in a given year and compared the inclusion rates of female authors against the presence of female scholars in the field. We also compared against female publication and citation rates in the field, and found that university syllabi introduce an added punishment for female authors (in terms of lower inclusion rates). The reasons for this may be found in the “canon effect” bias on the part of syllabi producers, a delay between institutional policy changes around inclusivity and their trickle-down into course materials, problematic citation practices, and other structural effects and discriminatory practices.

Harnessing the data-driven potential of syllabi is not necessarily a straight-forward process: there are similar challenges to what one might expect with other datasets. These relate to availability and access, representativeness, ownership, comparability, quality of data and methodology. While some syllabi are freely available online, others have only restricted access (e.g. accessible solely to students and instructors). It may therefore not be easy to gather large or even complete datasets of syllabi. In addition, the dual nature of syllabi (as scholarly products and as instruction tools) raises the question of ownership – to whom does a syllabus belong and is there a pedagogical burden of responsibility that they carry? Navigating such sensitive issues requires careful consideration of the legal, administrative, and ethical aspects of syllabi-as-data.

Finally, while most syllabi share common features, there is no universal blueprint. Different higher education systems, universities and instructors have very different policies and ideas regarding syllabus design. For example, reading lists at the LSE often have extensive additional readings sections. Elsewhere, syllabi may rely heavily on textbooks, or on a select few ‘canonical’ texts; other courses will focus on learning skills and practical tasks or rely predominantly on problem sets and software. This inevitably affects syllabus design and content. Increasingly, information that used to be recorded in written, often printed syllabi is being moved to online platforms which can be edited at a minute’s notice. The ever-changing nature of a syllabus lends itself well to temporal comparisons (e.g. a time-series analysis), but also means that comparing across syllabi requires clear methodological choices. The information necessary to investigate a pattern may not yet be present in the syllabus. For instance, to investigate author gender in our study, each assigned item in a course (article, book, etc.) needed to be coded for gender of the author. Yet gender data for authors is not readily available. Author gender therefore had to be imperfectly proxied through binary sex, even though gender need not align with biological sex.

Despite these challenges, the academic study of syllabi benefits our understanding of disciplinary histories and questions, knowledge (re)production, pedagogy and the teaching and learning of higher education. Combining critical perspectives on syllabus production with the methods of data analysis has the potential to shape institutional policies in higher education and transform the public discourse around what content and whose voices count as knowledge of a subject. Importantly, treating syllabi as data also creates more opportunities for collaborative, departmental or student-led research. It allows students to use the theoretical and methodological skills acquired in their studies to think critically about the learning experience and shape pedagogical and disciplinary debate (e.g. on decolonising the curriculum) by using data readily available to them. It might even change the way institutions, instructors, and students view the syllabus. What might alternative syllabi look like? Can the format of the syllabus be reimagined altogether? In this way, researching syllabi may in turn be a valuable tool towards reflexive, research-led teaching and learning.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions.

______________________________________________________________________________________________

*Image information and credits:

Main image: Photo by Ed Robertson on Unsplash