Paradoxes challenge conventional assumptions and can be profoundly shocking – so Catherine Allerton puts them at the heart of her course on children and youth. She explains why, and how students respond

Childhood can be considered to be a stage of life, before adulthood, that is universal to human experience. However, childhood is also a social and cultural construct. What it entails, the extent to which it might be different from adulthood, and whether it involves distinctive activities or culture, varies dramatically across time and space. Therefore, childhood is inherently paradoxical: both universal and constructed, both timeless and historically specific.

In teaching a course on Children and Youth in Contemporary Ethnography, I choose to embrace this aspect of childhood, and teach with paradoxes. I have found this a useful way to structure teaching and assessments. However, more fundamentally, teaching with paradoxes has also enabled students’ conceptual thinking and writing, as well as helping me demonstrate the theoretical power of taking childhood seriously.

It was this power of paradoxes to enable creative theorising and to question conventional assumptions that led me to make them central ...

Paradoxes and anthropology

A paradox is a situation or statement involving two apparently contradictory elements. Paradoxes contain two features that seem inconsistent. On the face of it, it seems impossible for both elements of a paradox to be true, and yet, somehow, they are. Take the paradox with which I began: that childhood is simultaneously a universal life stage and a social construction. When contemplating a baby, the idea that infancy – as a stage of childhood – is a social construction might seem very strange. And yet, while everyone recognises the distinctiveness of infancy, not everyone would subscribe to the Balinese view of infants as so holy that their feet may not touch the ground, or the Puritan view of babies as inherently sinful.

Paradoxical thinking is central to much anthropological theorising, which often involves the use of cross-cultural comparison to challenge stereotypes and generalisations. The economic anthropologist, Marshall Sahlins, made brilliant use of paradoxes in his essay, The Original Affluent Society. In this essay, Sahlins defines affluence in terms of the amount of time that people have for leisure, and argues that hunter-gatherers had more leisure time than any other type of society, given the relative ease with which they could meet their subsistence needs. The paradox of Sahlins’ essay is that while hunter-gatherers lacked money and many material possessions and thus appeared by conventional Western standards to be poor, their abundant leisure time made them simultaneously rich.

Paradoxes as critical and creative

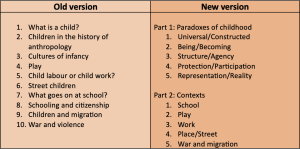

It was this power of paradoxes to enable creative theorising and to question conventional assumptions that led me to make them central to the way I taught my course on children and youth. I had previously taught this course in a more conventional way as a series of topics, for example Adolescence, Schooling and Education or Street Children. However, I found that these topics became somewhat disconnected from each other, and students would often only engage with those topics that felt most interesting to them.

By turning to paradoxes, I wanted to encourage the students to think across the whole course and also think more conceptually about research with children and youth. This seemed important, not only pedagogically, but also because there is a tendency to see studies of children as somehow less theoretically exciting than work with adults (the implicit focus of most academic thinking).

Paradoxical thinking, in which we try to deal with how it is possible for two inconsistent or opposed elements to be simultaneously true, involves embracing contradictions. This helps us approach apparently insolvable issues from a new angle, and be more critical and creative in our thinking. It also encourages a more nuanced approach to complex issues, rather than the search for definitive answers.

How the new version of the course compares to the old version in terms of organisation of topics

How the new version of the course compares to the old version in terms of organisation of topics

However, though paradoxes can encourage nuance and help avoid simplistic thinking, they can also be profoundly shocking. This is best illustrated by one of my favourite books that I teach, Myra Bluebond-Langner’s The Private Worlds of Dying Children. This ethnography draws on fieldwork on a child leukaemia ward in a US hospital. Bluebond-Langner outlines a situation where neither doctors nor parents explicitly reveal to the children on the ward that their cancer is terminal, but where the children nevertheless work out for themselves that they are dying. However, the most powerful part of her account describes how children then conceal their knowledge from the adults around them, in order to maintain mutual pretense regarding their childhood. I use this example in exploring the paradox of structure and agency in children’s lives, since these children agentively gain knowledge of something (the fact that they are dying) that no adult has ever told them. However, it also relates to other paradoxes that are central to childhood, including the paradox of innocence/experience and the related paradox of protection/participation. In this case, paradoxical thinking reveals the terrible toll on children of having to maintain adult fictions about the true nature of childhood: since children are the future, a dying child with no future becomes a category mistake.

Student responses

In general, I have found that students respond well to the structure of the course, in which five weeks on paradoxes are followed by five weeks on contexts within which the paradoxes can be further explored.

The assessment for the course also follows this structure, with students asked to explore one paradox in relation to any context of their choice, whether one discussed in the course (for example, schooling or play) or a context explored in the student’s own independent research.

In the classroom, and in assessments, students have space for different responses to the paradox under discussion. They can respond by accepting both elements as true, or by using the paradox to frame a situation in an unusual way, or by seeking a higher level of analysis. Because students have to focus their assessments on a paradox, they are forced to look for complexity in the examples they choose, and in the arguments they make. For some students this proves a troubling approach, particularly where students seem more drawn to an either/or answer. However, the majority of students respond positively, choosing to reformulate the paradox in a more subtle way, or to emphasise the links between different, interconnected paradoxes. Occasionally, students also introduce a new paradox – for example ignorance/expertise and agent/victim – as a way to think through a specific context of children’s lives.

In my course, I emphasise that conceptions of childhood are particularly paradoxical, since they often involve idealistic visions of childhood that are very different to the realities of many children’s lives. However, ultimately, it is also the case that we all have to live with paradoxes, and with the tensions and conflicts that they involve. Teaching with paradoxes has made the discussions and assessments on my course less predictable. It has encouraged students to question all-encompassing theories, and appreciate the creative potential of friction.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Main image: Annie Spratt on Unsplash