In this special issue, Yaprak Gürsoy and Özge Onsural-Beşgül bring together Turkish academics and scholars to discuss the recent and ongoing crises in Türkiye and their impact on the higher education sector

- This post is part of a special issue, Higher education during times of crisis in Türkiye

Last year, we commemorated the 100-year anniversary of the Turkish republic with a series of events organised by the Chair of Contemporary Turkish Studies at the European Institute, LSE. One of our cornerstone events was a two-day workshop organised in collaboration with the European Institute at Istanbul Bilgi University. During the workshop, we reviewed the accomplishments of the Turkish higher education sector in the past century, with a particular focus on the main challenges it still faced.

In the process, we uncovered a number of diverse crises that confronted Turkish universities in the last decades. It was not just the so-called “refugee crisis” that impacted universities; there have been other disruptions too. Some of these interruptions reflected global dynamics, such as the pandemic, while some seem to be in line with regional trends, such as growing political polarisation and Euroscepticism. However, there were also disruptions unique to Türkiye, such as the February 2023 earthquakes.

The collection of blogposts in this special issue reflects our discussions around these crises and their impact on the Turkish higher education sector. The posts focus on the personal experiences of academics during times of crisis, provide evidence from students’ perspectives, and reflect research findings.

The growth in the number of universities has not been accompanied by a corresponding rise in quality, resulting in inequalities between institutions

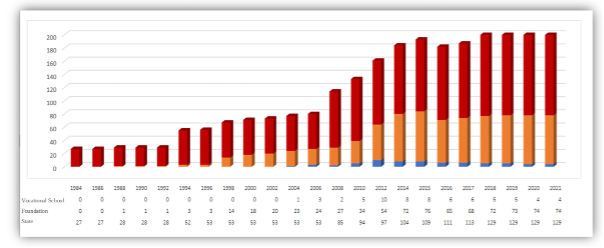

What makes this focus on higher education in Türkiye particularly interesting is the transformation the sector went through in a short period of time. The proliferation of the number of universities is one way to document this transformation. For comparison, in 2000, there were 53 state universities and 18 foundation universities (see the figure below). By 2023, the number increased to 129 state universities and 75 foundation universities, including four foundation vocational schools.

The number of state and foundation universities in Türkiye has increased significantly over the last few decades. (Source: Higher Education System in Türkiye)

The number of state and foundation universities in Türkiye has increased significantly over the last few decades. (Source: Higher Education System in Türkiye)

The proliferation of universities in Türkiye in recent decades has undoubtedly eased access to higher education. However, according to the 2020 Bologna Process Implementation Report, Türkiye still has one of the lowest figures in the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) in terms of the number of institutions per million. This is due, in part, to the rise in the number of university students in Türkiye – an increase of 71.8 % in just five years, from 2010 to 2015. Furthermore, the growth in the number of universities has not been accompanied by a corresponding rise in quality, resulting in inequalities between institutions.

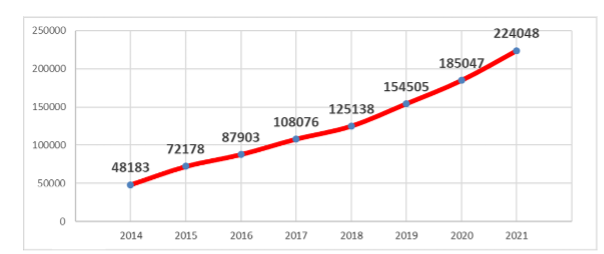

The number of international students in Türkiye has been increasingly steadily since 2014 (Source: Higher Education System in Türkiye)

The number of international students in Türkiye has been increasingly steadily since 2014 (Source: Higher Education System in Türkiye)

Turkish central state authorities initiated reforms to address these and other challenges in the early 2000s. Some of these actions took place during the Bologna Process and could be understood from the perspective of Europeanisation or internationalisation, as summarised in Kaya’s and Onursal-Beşgül’s post. The Bologna Process reforms had a significant impact on universities, academics, and students, but these stakeholders were passive recipients, unable to influence the trajectory of change, leading to a lack of internalisation. As political and social tensions grew in Türkiye and as prospects of EU membership stalled, the Bologna Process lost its momentum, further making it difficult for the reforms to have a positive impact on the ground. In some cases, faculty members and students opposed central government decisions and policies, leading to prolonged protests and resistance movements on a number of university campuses, most notably at Boğaziçi University.

The increasing number of transnational students required a different approach to education

The loss of steam in the reform process and rising tensions also coincided with the start of the civil war in Syria in 2011 and the arrival of more than three million refugees. As Çayır and Dereli address in their respective posts, the increasing number of transnational students required a different approach to education, starting from primary schools and continuing on to universities. The top-down approach adopted by the Turkish Ministry of National Education (MoNE) was to initiate projects on inclusive education, along with easier access to universities for foreign nationals. However, Çayır shows that the MoNE projects have so far failed to change student perspectives on nationalism partly due to an insistence on a centralised approach. Dereli’s study takes a different perspective and focuses on the experiences of refugees themselves and shows how some refugees feel at home on campus. Based on her findings, Dereli calls for more research delving into the experiences of students to complement studies providing a more macro-level approach.

A similar process of top-down policies leading to unexpected or insufficient results on the ground is evident in the posts of Tuğtan and Tunç, who each demonstrate how the Council of Higher Education-mandated online teaching, as a response to the pandemic and earthquakes, led to mixed results. Reflecting on their personal experiences at Istanbul Bilgi University, which is a Turkish foundation university, they demonstrate the challenges administrators face during sudden disruptions. In both, the pandemic and the earthquakes, responses required quick and unusual activities beyond the guidance of national and centralised institutions.

In both, the pandemic and the earthquakes, responses required quick and unusual activities beyond the guidance of national and centralised institutions.

Tuğtan argues that although remote teaching was successfully initiated during the pandemic, the negative experiences led many academics to resist online and blended education later, negating years of progress in this area. Despite the investment in online education before lockdown, the scale of the pandemic and lack of general guidance led to difficult transitions to and from emergency remote teaching. Similarly, Tunç chronicles the myriad initiatives the university introduced in the immediate aftermath of the February 2023 earthquakes. As the Vice-president of Istanbul Bilgi University, she provides an overview of the range of actions the university administration had to consider, from communicating with students and staff to organising rescue and aid teams. She discusses the emotional weight of these decisions, reflecting on the difficulties of being a university administrator at a time of an unprecedented natural disaster.

Together, the posts in the special issue highlight how dedicated work by individual faculty members and administrative teams can mitigate the impact of crises, albeit to an extent. However, these experiences are still valuable as knowledge from the universities and campuses can aid in developing a more comprehensive understanding and better policies, leading to better collective outcomes. In light of the unpredictable nature of the future and the potential for more crises, continued insights from universities and campuses will play a pivotal role in developing adaptive strategies and fostering resilience in the higher education sector.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________ This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions. _____________________________________________________________________________________________

Image credits:

Main image: Centenary workshop organised by LSE and Istanbul Bilgi University. Courtesy LSE Contemporary Turkish Studies

Graphs (Institutions in Türkiye and International students in Türkiye): Higher Education System in Türkiye