What happens to a so-called emergency tool when the emergency is over? Mehmet Ali Tuğtan explores how online learning’s greatest opportunity also became its setback

- This post is part of a special issue, Higher education during times of crisis in Türkiye

During the Covid-19 pandemic, higher education institutions worldwide kept education going under complete lockdown conditions. Online education systems, which had been designed to complement traditional face-to-face programmes, were instead used to replace them. In Türkiye, the entire transition had to be completed in a matter of days. In the years before the pandemic we had developed and refined course conversion systems to produce high-quality blended and online courses. We had to throw these out as we rushed to play our part in the largest mass conversion of course delivery methods in the history of higher education. To distinguish this from what we normally do, we called it Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT). However, not only did the pandemic disrupt our earlier work in online/hybrid education, but the negative experience of ERT has led to a post-pandemic backlash against online/hybrid education in general.

The pivot

Since 2017, I have been responsible for the academic and administrative management of the Distance Education Centre (UZEM) at my home institution in Türkiye, Istanbul Bilgi University. To fully digitise our face-to-face courses, our pre-pandemic blended conversion model envisaged a two-stage adaptation to address the needs of two different groups of learners: undergraduates who value the physical campus experience, and others who value degree completion for professional goals. We assumed that undergraduates needed socialisation on campus as much as they needed structured academic education and degree completion. Therefore, our objective was to create more blended courses for undergraduates and a wider range of fully online courses for graduate, professional, and lifelong learning programmes. By the start of 2020, we had converted more than 300 courses to online and blended delivery methods, with student satisfaction levels on par with face-to-face courses.

When the pandemic hit, our seven-member operations team and three part-time pedagogical consultants managed the conversion of 1,815 courses delivered by 850 instructors to 20,000 students in five days! During the first two months of ERT, we conducted 23 webinar sessions on the pedagogical and technical aspects of distance education, covering 11 different technical and pedagogical topics for 2,836 live participants. All sessions were recorded and edited by UZEM’s post-production team to be added to our online training resources. Our IT department increased the university’s internet uplink bandwidth by 50% to maintain connectivity and speed. To coordinate our efforts with the academic programme leads, a faculty member was appointed as an online coordinator in each academic programme, whose responsibilities included weekly reporting of academic activities to the corresponding dean, UZEM, and the rectorate.

This was indeed a novel, but not entirely unfamiliar, experience for the students, especially Generation Z. While isolation from campus was a universal concern, the academic impact was felt more or less negatively depending on access to the internet, hardware, and personal space to follow online courses at home, with poorer students disproportionately affected.

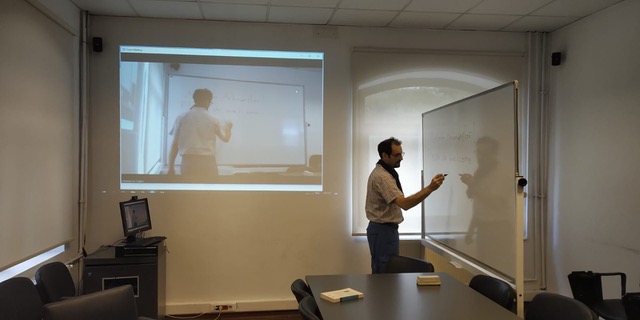

Teaching alone: Bilgi IR lecturer, İnan Rüma, conducting a live classroom broadcast on Zoom.

Teaching alone: Bilgi IR lecturer, İnan Rüma, conducting a live classroom broadcast on Zoom.

Uncharted territory

However, ERT was a blunt trauma for the faculty (who ranged in age from boomers to millennials). For the majority, this was their first exposure to online education as instructors. They had not planned, prepared, or signed up for this work. There was nowhere near enough staff, resources, or time to train them properly. They had to worry about the impact of the pandemic on their own lives, in addition to the stress of venturing into the unfamiliar terrain of online education. Some did not understand the limitations of the online method and how it differed from face-to-face training. As a result, they became frustrated when they could not do things the way they were used to in class.

For most distance education practitioners at the time, that was our measure of success: keeping education going

Most of what we were doing was uncharted territory: no one had ever tested these systems (the hardware, software, or connectivity) on this scale. There was no pedagogy, no virtual classroom tools, no digital support materials that could successfully replace face-to-face education by online means alone. The regulations did not anticipate the need for fully online education under the complete lockdown created by the pandemic. So the public authority, in our case, the Council of Higher Education, which had restricted the number of courses that could be delivered online before the pandemic, gave individual institutions wide latitude to manage the new process. We had to make do with what we had and improvise to keep things going. For most distance education practitioners at the time, that was our measure of success: keeping education going.

A wall of indifference

During the ERT, a comparative study between three universities, Northcap University of India, Universidad Latina de Costa Rica, and Istanbul Bilgi University, found that 39.3% of Bilgi students liked the flexibility offered by digitalisation, and 23.9% liked not having to travel to campus every day. So it was no surprise that 50% of students wanted a hybrid curriculum after the pandemic. As for the Bilgi faculty, while 73% felt that online courses were less engaging, 60% agreed that future education should be more hybrid. These percentages mirrored the preferences of students and faculty in the other two institutions, across cultures, academic programmes, and other variables. So we expected the university administration to take stock and design the new curriculum accordingly.

online education was some kind of emergency tool and that the emergency was over

By the spring semester of 2022, when vaccination programmes allowed a safe return to face-to-face teaching, the Council of Higher Education reinstated (and in some cases tightened) restrictions on the degree of digitisation and hybridity of face-to-face programmes. At Bilgi University, many faculty members returned to full face-to-face teaching rather than hybrid delivery methods after the pandemic. When asked why, the response was usually “because the online thing doesn’t work and we don’t need it anymore”. Counter-arguments about the difference between blended and online methods or between online education in general and ERT hit a wall of conservatism and indifference. This attitude on the part of faculty was tolerated and, in some cases, encouraged, by the academic leadership, who had also come to the conclusion that online education was some kind of emergency tool and that the emergency was over. As in other industries, management wanted their employees back in the office. The result was a decline in investment in online education after the pandemic. Budgets were cut, R&D was abandoned, and staffing levels in distance learning centres shrank.

I expect this attitude to be temporary. The pandemic experience has led to a growing body of literature on how to make online education more engaging at a lower cost and scale. Hybridity and modularity continue to be key student demands. The economic downturn and cost of living crisis, coupled with higher unemployment and student debt, are driving demand for better, higher-quality education that is easily accessible. This cannot be achieved without higher and new forms of hybrid education. Thus, in the long run, the price we, as distance education professionals, are currently paying for the success of ERT will not be in vain.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________ This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions. _____________________________________________________________________________________________

Main image: Mehmet Ali Tuğtan