Sam LeBas is a comic book editor and journalist from Louisiana. She works with the independent publisher ComixTribe, editing comic books, as well as helping aspiring creators learn about the process of making and publishing comics. In addition to writing comic book reviews and related articles, she is the co-author of a monthly Batgirl column for the Eisner-Nominated site Multiversity Comics. Find her on Twitter as @comicsonice

Will Brooker is Professor of Film and Cultural Studies at Kingston University. He has written extensively on comic books and their audiences, and co-authors a column on Batgirl for the Eisner-Nominated site Multiversity Comics. His next book is the co-edited Many More Lives of the Batman, in 2015. He tweets as @willbrooker

Click here for the introduction to the Comics, Human Rights and Representation Week.

Sexism in the comic book industry exists. As obvious as that might seem, as much of a cliché as it may have become, I still find myself arguing the point. I edit and review comic books, and enjoy the privileges that come with an exhibitor pass at comic conventions. I am part of the industry, and most of the time I have been lucky enough to work with men I respect, who respect me. Despite, or maybe because of, the fact that they take my work and opinions seriously, they often do not recognize that sexism within the industry is a reality, a point I debated for the ten-thousandth time during New York Comic Con 2013. I found myself perched on a barstool, the only woman in a room full of men, who were asking how I could possibly say the industry had any sort of bias against women. To prove a point, I asked them if they ever thought that I would be able to write Batman on an on-going basis, not a fill-in or a special, but if I could be the main writer on the title. It got quiet.

The answer was, and is, “no”. A woman is never going to be the writer of Batman on an ongoing basis: not any time soon, at least. There are two striking things here. Firstly, we all knew the answer, and secondly, it had never occurred to them that this was a problem. In thinking about why a group of men who have been supportive of my career in comics might be able to remain completely unaware of sexism within the industry that we are all a part of, I realized that the framework of the industry itself creates the problem.

The two most well-known comic book publishers today are Marvel and DC, and these well established companies set the standards for the industry. “The Big Two”, as they are called, publish superhero comics almost exclusively. As a medium, superhero comics were created for children – both boys and girls – but the fandom has evolved into a majority male, and mostly-adult, community. When adult men embrace attitudes and behavior intended as juvenile male fantasy, problems are inevitable. The pure ego associated with adolescent male escapism does not lend itself to socially aware, fair stories.

The entire institution of superhero storytelling, then, is founded on ideas which are essentially geared toward perpetuating a sense of male entitlement, and selling that idea as “part of the fantasy”. One key problem with superhero comics today is that sexism is acknowledged, but met with a “so what” attitude that completely negates the experience of anyone outside the target audience of straight, white men.

The industry has constructed a framework that is exclusive by its very nature; an exclusion inherent at every level, from narrative, characterization and visual depiction to the views and opinions regularly expressed by creative teams and industry executives.

Traditionally, men in comics have been physically idealized, aspirational and empowered: a fantasy of what boys could become. Women in superhero comics are the other side of that fantasy. While men occupy the position of the ideal subject, women are not only idealized, but sexualized and objectified. If male characters are representative of what readers would like to be, the female characters are who they would like to be with; or, commonly, what they would like to possess. If the men possess extraordinary agency, women are receptors for that agency, waiting to be acted upon. Every difference between the traditional expressions of gender is heightened and refined. The relationships between superheroes operate within a fantasy space, following rules and conventions that accentuate the privilege of male characters and make their entitlement seem natural and inevitable.

In 1999 comic writer Gail Simone wrote on her blog that a disproportionate number of female superheroines “have been either depowered, raped, or cut up and stuck in the refrigerator.” Simone, with the help of other comic book fans, compiled a list of female characters that were treated this way. This became known as “The Women in Refrigerators Project.” The title refers to a fictional episode that took place in Green Lantern #54 written by Ron Marz, in which Alex DeWitt, love interest of the title character, was killed and hidden inside her boyfriend’s refrigerator. The trope Simone describes is now widely acknowledged, and the practice it describes has come to commonly known as ‘fridging’. The superhero genre typically depicts interactions and relationships between male and female characters that lack consequence, emotional resonance, permanence and accountability. Often, these fictional relationships stagnate, or end tragically. Too often, women in superhero comics become pawns in schemes meant to develop male characters or give them motivation to act. Thus the avoidance of intimacy by male characters can be made to seem altruistic. By making it seem admirable for male characters to keep an emotional distance from their vulnerable counterparts, the significance of relationships with female characters, and the characters themselves, are trivialized.

There is an interesting, overlooked dichotomy in the fact that superhero characters who are meant to be socially conscious representatives of justice are guided by such irresponsible and reactionary attitudes. Through their position – within comics and broader popular culture – as role models, the heroes themselves help legitimize the idea that comic books are “a natural preserve for men,” as Todd McFarlane so eloquently stated during a 2013 interview. Indeed, some creators and executives treat the world of superhero comics explicitly as if it were a boys‘ club, and make active efforts to preserve its exclusivity. They stake out their claim on the space unapologetically, almost as if armed with ‘No Girls Allowed’ signs. The heroes’ pervasive lack of social conscience with regard to women is treated as tradition, and excused by the idea that comics are not intended for female readers. However, since the superhero genre has moved into mainstream media on such a large scale within the last decade, these conventions are changing.

What does it mean that the superhero genre has recently become so ubiquitous, spanning all media from movies to clothing to video games? Sexism is being met with a stronger backlash, as a broader audience breaks into the boys’ club. What was for decades a niche market has now attracted the attention of a far more diverse fanbase, and the expansion of comics communities from letters pages and fanzines to social media means that those fans are more able to speak out, to form communities, and to campaign collectively. Moving across media makes comics more visible, and more accountable.

The impulse to change the way women are depicted in superhero comics is evident in this 2014 character design sketch from Batgirl team Brenden Fletcher, Cameron Stewart and Babs Tarr. The text specifically notes that their rebooted version of the character will not be wearing spandex, and contrasts the silhouette of a more traditional uniform against her practical leather jacket.

Similarly, Spider-Woman’s image has recently undergone a major overhaul. Like her DC counterpart Batgirl, the Marvel superheroine now wears utilitarian clothing as seen in this character design by artist Kris Anka.

Perhaps the most striking makeover in the current lineup of Big Two titles involves Gwen Stacy, Peter Parker/Spider-Man’s love interest. Before her appearance in The Edge of the Spider-Verse #2, written by Jason Latour, Gwen was dead, and had been since The Amazing Spider-Man #121, published in 1973. Today, in Latour’s alternate universe, Gwen has superpowers, and Peter is dead. Her costume design, by Robbi Rodriguez, and her revived, rebooted character have been embraced by readers to the point that she will be given her own book, complete with the affectionate nickname Spider-Gwen, in February 2015.

Latour cites Gwen’s popularity in other media (presumably in the The Amazing Spider-Man film franchise, where she was played by Emma Stone) as one of the reasons they were able to bring new life to this character; just one example of how other media portrayals of superhero characters are influencing their source material, the original comics.

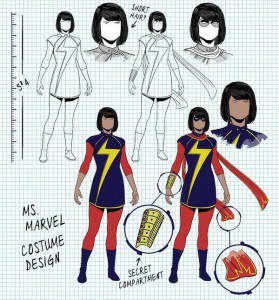

Another notable example of these shifting expectations for superheroines is Ms. Marvel. In 2014 Kamala Kahn, a Pakistani-American girl from Jersey City, took up the mantle. Her costume is more conservative than her predecessor and her storylines are aimed toward a younger female audience.

With the debut of Ms. Marvel #1 by Sana Amanat, G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona, Kamala Kahn became the first Muslim character to be given her own title at either of The Big Two companies. It’s worth mentioning that that the previous Ms. Marvel, Carol Danvers, is now the title character in her own series, Captain Marvel. Before the reboot of that title, written by Kelly Sue DeConnick, Captain Marvel was a moniker used primarily by male characters. And in October 2014, the same month as Batgirl’s DC reboot in a more sensible costume, Marvel released a new version of Thor, written by Jason Aaron, with a female lead.

Perhaps the representations of these characters signify a major shift within the industry itself. Market research conducted in 2014 estimates the percentage of female comic readers may be as high as 46.67%. A growing diversity of art, representation, character and story outside the commercial superhero genre, in books such as Saga by Brian K Vaughn and Fiona Staples and Pretty Deadly by Kelly Sue DeConnick and Emma Rios (both published by Image Comics), is starting to influence and become incorporated into the mainstream, along with more female creators.

Previously, representation and institutional male editorial were part of a closed circuit, a chain, a joined up system where the way gender roles were represented was inherently connected to the people in control of those representations. The changing depiction of women in superhero comics has gone hand-in-hand with a shift, however small, in the male/female ratio within the industry itself.

It’s telling, though, that female creators are having to be tempted from outside the medium, from literature and video games – testament to the fact that women’s historical place inside comics is still overlooked, and that they have never been particularly welcomed – and we could also ask whether this deliberate inclusion and foregrounding of a few high-profile women risks appropriation and tokenism. Are these only superficial changes to the boys’ club, or the start of something more fundamental?

Click here to read the rest of the articles in the Comics, Human Rights and Representation week.

good sharing many thanks

Very knowledgeable mam.