In Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization: Practical Tools for Improving Teaching, Research, and Scholarship, Abby Day, Lois Lee, Dave S.P. Thomas and James Spickard bring together academics from across the globe to explore tangible actions those within the academy can take to foster diversity, inclusion and decolonisation. If there were a global syllabus for academics, this collaborative work should be required reading, writes Ellen Frank Delgado.

This blogpost originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact the managing editor of LSE Review of Books, Dr Rosemary Deller, at lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization: Practical Tools for Improving Teaching, Research, and Scholarship. Abby Day, Lois Lee, Dave S.P. Thomas and James Spickard (eds). Bristol University Press. 2022.

Over the past few years in academia, I have been invited to countless diversity, inclusion and decolonisation seminars. Panels, talks, fireside chats, film screenings, training, book clubs, paper presentations. When these invites pop up in my inbox, they spark a sense of hope in me that academia is at the precipice of change. It affirms that there are people within the academy who care about these issues and are willing to go above their job requirements to create meaningful transformation. At the same time, once I attend, I can feel discouraged. While coming from a genuine place and driven by intelligent and caring colleagues, these seminars often remain fluffy. They lack any real substantive actions for long-term change. This is why Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization is so needed, and why I personally craved a book like this. The title drew me in, but the actual practical tools provided throughout kept me reading; they kept me hopeful.

Over the past few years in academia, I have been invited to countless diversity, inclusion and decolonisation seminars. Panels, talks, fireside chats, film screenings, training, book clubs, paper presentations. When these invites pop up in my inbox, they spark a sense of hope in me that academia is at the precipice of change. It affirms that there are people within the academy who care about these issues and are willing to go above their job requirements to create meaningful transformation. At the same time, once I attend, I can feel discouraged. While coming from a genuine place and driven by intelligent and caring colleagues, these seminars often remain fluffy. They lack any real substantive actions for long-term change. This is why Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization is so needed, and why I personally craved a book like this. The title drew me in, but the actual practical tools provided throughout kept me reading; they kept me hopeful.

The collection is divided into four main parts, each focusing on a different aspect of transforming the ivory tower: changing universities themselves; diversifying curricula; diversifying research and scholarship; and overcoming intellectual colonialism. The format highlights how universities, if they are going to be transformed, need to be addressed at every intersecting layer of their complex and longstanding structure.

Each section is threaded together by a few underlying themes. First, academia is part of the wider phenomena of neoliberalism and postcolonialism. Second, universities are sites of knowledge (re)production. Lastly, if academics are ever going to truly decolonise the academy themselves, if this is even plausible, the operation will be a gruelling, grief-filled process of mass deconstruction.

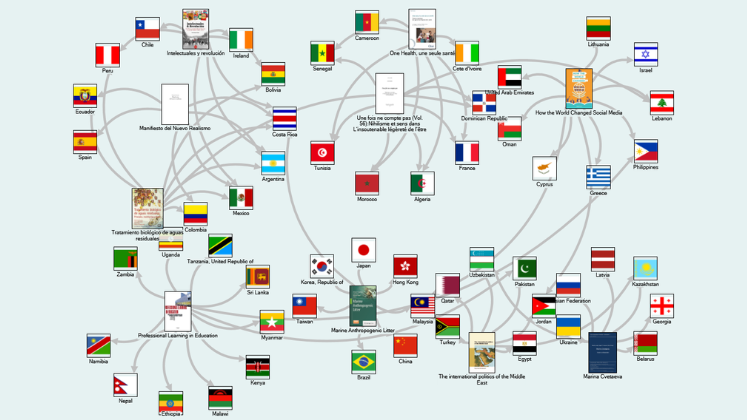

To begin, at the heart of this book’s argument is how education is an American and European product, bought by student-consumers: ‘Eight of the top ten countries sending most international students to UK universities are former colonies’ (Lin Ma, 49). This shows how the Global North has a chokehold on knowledge production, even as consumers increasingly come from the Global South. In our neoliberal capitalist society, universities sell education as an elite product. Most academics at UK universities will be familiar with the idea of ‘cash cow’ students, whereby incomprehensibly high international student fees are seen as the bread and butter of university funding.

This elite educational product is even more limited by the oligopolistic grip of academic publishing. In fact, ‘by 2013, just five publishers were responsible for half of all journals, papers, and citations’ (Paige Mann, 187). As consumers of elite education become more global and diverse, the disconnect from the few who are producing, hoarding and legitimising knowledge only grows. It prompts the question of whether universities can ever be liberated from the neoliberal capitalist and postcolonial systems that keep them alive.

The book’s second theme focuses on the violence of knowledge (re)production: the lack of pluralistic knowledge structures, overreliance on the canon and the perpetuation of oppression. On the one hand, academia, especially in introductory courses in the Global North, must teach the traditional canon of a particular field. Yet, in doing so, academia is engaging in ‘epistemicide’ by declaring who the authorities in a field are. ‘Epistemicide’ was coined by Boaventura de Sousa Santos (2005) and involves the destruction or delegitimising of non-dominant forms of knowledge production (Karen Bennett, 2007).

Thus, set curricula kill knowledge systems by positioning them as outside the normative. They paint them as falling beyond the neutral, trustworthy grounds of the academic literature. The works of those who are not deemed an authority, especially those who engage with ‘image, poetry, sound and symbol’ (Danny Braverman, 77), are often ‘recast as merely superstition, ‘‘magic’’, tradition, or pre-modern’ (Ali Meghji, Seetha Tan and Laura Wain, 39). While this epistemicide does not include acts like genocide or the dramatic burning of literature, it is nonetheless violent. This violence grows in the academy as ‘classrooms are a space of knowledge (re)production’ (Denise Buiten, Ellen Finlay and Rosemary Hancock, 141).

To counteract this, Euro-American academics must ‘value Southern thought regardless of its Northern applicability’ (Meghji, Tan and Wain, 44). We must redefine what the canon is, address the biased limitations of the academic literature and foster plural knowledge structures beyond the traditions of the scientific method through ‘communities of practice’ (Sara Ewing, 136).

If decolonising the university means completely renovating its neoliberal, capitalist and postcolonial foundations while redefining what knowledge is, it is clear why this book does not include an easy ten-step guide for academics. Simply put, there is no straightforward to-do list to follow.

If there was, perhaps one starting point would be clarifying what exactly is meant by diversifying and promoting inclusion in a decolonised academy. The book never defines these terms, but mentions that they may overlap and intertwine. Interestingly, academia as a whole lacks an agreed definition of inclusion, with some defining it as participation and contribution (Quinetta Roberson, 2006), and others as feelings of uniqueness and belongingness (Lynn Shore et al, 2011). At times, it feels as though the collaborators also have varying definitions in this book, posing the question of how can we collaboratively work towards that which we may be understanding differently? This lack of clarity is seen in such statements as ‘diversity and inclusion work needs to be diverse and inclusive’ (Samantha Brennan, Gwen Chapman, Belinda Leach and Alexandra Rodney, 92).

In reading through the collection, it nonetheless emerges that diversity and inclusion, however they are interpreted, are inevitable in striving for long-term, sustainable decolonisation. The book provides ample examples of how universities can lead in diversity and inclusion. For instance, they can recruit students and staff across diverse dimensions (race, gender, sexual orientation, disability status, class, nationality, etc). They can ensure these students and staff are enrolled, supported and succeed at university. Curricula can be revised to be more inclusive too. However, even when universities are promoting diversity and inclusion, they are not achieving complete decolonisation of their colonial structures.

In this way, the plausibility of ever really decolonising the university itself transpires as a question. Some collaborators in the collection feel adamant that decolonisation is possible. Even so, I most align with the few who hint at their distrust of this call for decolonisation. I struggle, even after reading this book, with answering the question of how do we, as academics, devote 40+ hours a week simultaneously to our university’s growth and its deconstruction? We are, hypothetically, aiming to destroy that in which we have found our lifelong passions and careers. There is a glaring dissonance, not to mention a big ask, there.

In decolonising the academy, smaller actions like curricula expansions are feasible. Long-term structural changes to the academy itself require massive collaborative reform. We must keep in mind that not all academics will want to destroy their institution. With that in mind, can academics (the very people who have kept the academy alive and well) even be the ones to drive this reform? This paradox appears when we coerce students into marking systems that call for assimilation into the academy. It also appears when we propose diversity and inclusion policies without changing the very exclusive and bureaucratic foundations on which all universities are built. Although this book advertises practical tools for addressing decolonisation of the academy, perhaps the complete decolonisation of universities by academics is, unfortunately, implausible.

If my pessimistic viewpoint is true, then perhaps academics cannot be the ones to reform universities for this very reason; we are too close to the institution itself to make structural changes that would lead to its destruction. After all, as the editors argue, drawing on the work of Andrew Seal (2018) and David Harvey (2015), ‘this neoliberal university […] favours diversity initiatives to the extent that they train graduates to work with whatever kind of people best serve the neoliberal system’ (252). Real change is going to mean real loss, and grief, for academics. Diversity, Inclusion, and Decolonization successfully shows how we can improve universities. Its limitation, though, is that academics may not be the ones to come together to successfully decolonise and rebuild the institutions to which we belong.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Tim Hüfner via Unsplash