During the COVID-19 pandemic it was regularly highlighted how the pandemic would create an opportunity for virtual/digital innovation and a reset of established ways of working. Reflecting on research carried out at the height of the pandemic, Sonja Marzi and Jen Tarr argue that in an increasingly precarious world, hybrid participatory methods offer new ways of doing engaged and international research taking advantage of both offline and online worlds.

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to feel like a distant memory for many researchers, and face-to-face fieldwork and data collection have re-started, including in transnational research. However, whilst it may be tempting to revert to old ways of doing research, we should learn and reflect on innovations introduced during the pandemic. Particularly for co-production and participatory researchers, the need to shift research online, produced challenges, but it also opened up new opportunities to design and rethink collaborative research projects.

During the pandemic participatory researchers, like us, were able to bridge geographical distance through online engagement with participants. Yet, we also realised that online spaces cannot fully compensate for face-to-face participatory research activities, either in terms of data quality, or building relationships of trust between researcher and participants, especially for research on sensitive topics. However, hybrid qualitative and more specifically co-production and participatory research designs involving online and ‘present in person’ research activities present an opportunity to bridge the advantages of both approaches, while mitigating the challenges.

We therefore argue for developing and embedding more hybrid participatory and co-production research designs that combine remote/online with face-to-face research activities to co-produce knowledge with participants now. In a changing research landscape affected by climate and health emergencies, humanitarian disasters and conflict, social upheaval and multiple crises in many countries, hybrid participatory methodologies have not only become more relevant, but are an essential addition to social science toolkits.

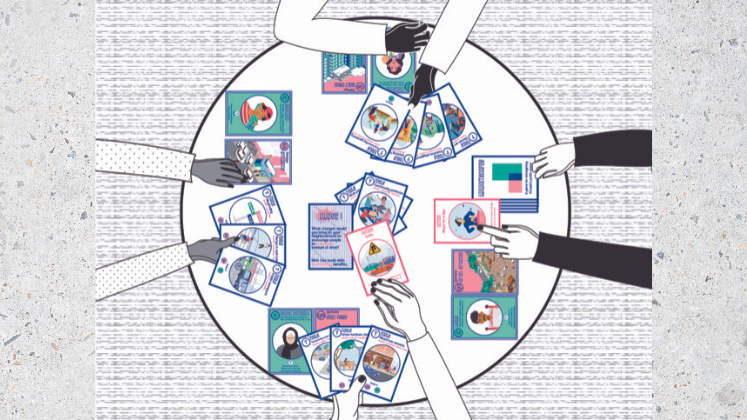

In our research we successfully developed an innovative remote participatory methodology using smartphones, to co-produce knowledge and a documentary with displaced women in Bogotá and Medellin, Colombia. This remote methodology offered insights into women’s past and present lives during emergencies (COVID-19 and the National Strike in Colombia), while at the same time it bridged geographies by curating an inclusive online space with non-hierarchical practice at its core. It also allowed for more equal research relationships between transnational researchers and participants, by including them in the whole research process and thus enabling them to contribute to ideas of how we could decolonise our research. Specifically, in our work we used smartphones for remote participatory filming and online workshops as well as face-to-face workshops to meet in person and discuss the content of filmed material. While the innovative online/remote filming method allowed us to connect online over a period of over 10 months to co-produce knowledge and a documentary, face-to-face workshops overcame limits to participation and technological problems and allowed for the discussion of more sensitive issues women felt difficult to discuss online.

As a result of testing this hybrid co-production research design, we strongly believe there are ethical and practical reasons why these kinds of research designs can become the best long term solution to co-produce knowledge with participants for impact and social change and to reimagine how fieldwork could be different in the future. Here we outline five key reasons why we believe this to be the case:

1. Hybrid co-production methodologies ‘future-proof’ research projects in light of the normalisation of disruption to travel and face-to-face social contact affected by emergencies and the climate crisis, especially (although not exclusively) for transnational Global North-South research collaborations. While much research did shift online during the pandemic, often advice was given with a short timeframe in mind. Crisis, emergencies and disaster, however, are in many places endemic and the climate crisis especially demands serious ethical reflections.

2. This point is also valid for contexts of violence and insecurity where researchers may struggle to enter the field ethically, safely or logistically.

3. In our research we included local researchers in Colombia as equal research team members and increasing arguments for decolonising research practices through valuing local knowledge are one of the drivers of our development of a remote/hybrid participatory methodology. Such methods allow for greater transnational collaboration and thus aim to shift power within the research process in more sustainable ways, as well as allowing for more ethical and long-term research commitments.

4. Funding restrictions limit travel and fieldwork opportunities. Combined with rising inflation and energy costs, especially for early career scholars, it is increasingly challenging to conduct transnational co-production and participatory research, which includes traditionally staying a prolonged time overseas to build trust with communities and do a lot of face-to-face work with participants.

5. Hybrid research offers more inclusive research processes: giving participants more choices over when and how to take part. This is especially important for participants who are time poor and juggle work, caring and community responsibilities. The same goes for the researchers themselves, who may struggle to find the funds, time and support to take over their care responsibilities and to be able to travel for research purposes. It, therefore, allows for bridging space, reducing travel time for participants and connecting groups that could not meet face-to-face otherwise easily; e.g. being located in two cities.

Combining recently acquired methodological innovations with more traditional face-to-face co-production research approaches could potentially open new types of long-term collaborations with participants. Hybrid co-production research processes offer opportunities to connect with participants throughout the process, to get feedback from them during data analysis and include them online in dissemination activities. Our project with women in Medellín and Bogotá demonstrated how connecting online and face-to-face creates these kinds of long-term relationships, where we were able to do exactly that, ask for feedback, organise dissemination events, create impact projects that go beyond the initial research, while in the process bridging neighbourhoods, cities and continents. Thus, hybridity facilitates continued inclusion of participants after face-to-face research is concluded, and potentially leads to more impactful research practices benefiting participants during and beyond the research process with the ability to respond better to participants’ aspirations and needs. As the world continues on an unstable trajectory hybrid co-production processes offer a way to continue to work together across time and space to create research for a better world.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Reproduced with permission of the authors.

Are there any risks or challenges associated with including participants in the data analysis and dissemination activities online?

Excelente reflexión. Muy interesante la mirada sobre lo cualitativo, está de lo híbrido. En una red latinoamericana estuvimos reflexionando sobre las métodos de frontera.

Me gustaría poder conocer más de su trabajo y poder intercambiar ideas