In the past the preservation of the scholarly record relied on physical print publications being archived in multiple places by different institutions. In principle this holds true for digital preservation, where a number of organisations work to preserve the scholarly record. However, drawing on a study of Crossref DOI data, Martin Eve finds evidence to suggest that the current standard of digital preservation could fall worryingly short of ensuring persistent accurate record of scholarly works.

We have become used to the digital availability of the scholarly record. Almost all academic journals are now electronically accessible and their availability on the web is taken for granted.

We also know that the entire epistemological endeavour of research depends upon the continued availability of scholarship. As Anthony Grafton puts it in his history of the footnote, ‘the culturally contingent and eminently fallible footnote offers the only guarantee we have that statements about the past derive from identifiable sources. And that is the only ground we have to trust them’. Yet, if we can’t persistently access those sources, then we also can’t trust them.

In my role as Principal R&D Developer at Crossref, I undertook an experiment to ascertain the volume of scholarly digital material that is adequately preserved. It is a condition of Crossref membership and the assignment of a Digital Object Identifier (DOI) that publishers make best efforts to ensure that material with such a DOI is deposited in third-party archives.

To ascertain the lie of the land, we looked at 7.5 million DOIs and checked them against public records of major scholarly archives: Cariniana, CLOCKSS, HathiTrust, Internet Archive / FATCAT, LOCKSS, PKP PLN, Portico, and Scholars Portal. Most of these archives only specify that they have preserved a volume or issue, rather than a specific item, so we had to negotiate between the item-level metadata of the work itself and the container-level information provided by the archive.

Most worryingly, 32.9% (n=6,982) of Crossref members seem, using our dataset, not to have any adequate digital preservation in place, against the recommendations of the Digital Preservation Coalition

Of course, these archives are not comprehensive. It is entirely possible that material that we checked appears in other locations, such as Figshare, which is backed by the Chronopolis digital preservation system at the University of California at San Diego. Much material is also stored in “green OA” institutional repositories. However, as a starting point, these archives give relatively good coverage and allowed us to appraise the situation.

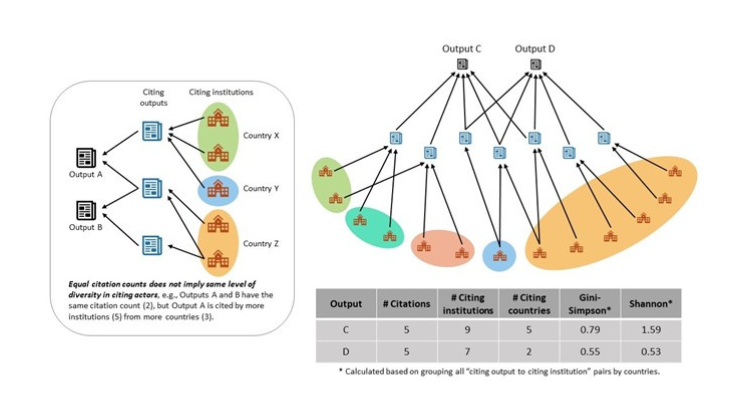

Our findings reveal a scholarly landscape with an imperilled digital future. Only 0.96% of Crossref members (n=204) could be detected to preserve over 75% of their content in 3 or more of the archives that we studied. A slightly larger proportion – 8.5% (n=1,797) – seemed to preserve over 50% of their content in 2 or more archives. Many members – 57.7% (n=12,257) – though, only met the threshold of having 25% of their material in a single archive, that we could detect. Most worryingly, 32.9% (n=6,982) of Crossref members seem, using our dataset, not to have any adequate digital preservation in place, against the recommendations of the Digital Preservation Coalition (see Fig.1).

Fig.1: Crossref members’ preservation statuses

When we looked at the works themselves, rather than members, the situation was not much better. In the 7,438,037 works examined, there were 5,913,102 ‘preservation instances’. This is a term denoting the number of stored copies. Hence, a single work that is preserved in three archives has three ‘preservation instances’. As an example: if I examined three works total, and one of them was stored in three archives, while the other two were stored in no archives, there would be a total of three preservation instances. Further, 4,342,368 of the works that we studied (58.38%) did have at least one preservation instance. However, this left 2,056,492 works in our sample (27.64%) that seem unpreserved. The remaining 13.98% of works in the sample were excluded either for being too recent (published in the current year), not being journal articles, or having insufficient date metadata for us to identify the source.

Another question that we can address from this dataset is: which categories of Crossref members do things well? And which have room for improvement? While we might expect well-resourced publishers in the highest revenue category of Crossref membership to have the best digital preservation practices, only one of the largest members (Elsevier) scored in this category. Meanwhile, ‘smaller’ members (even those with publishing revenues of $50 million USD) fare worse. Finally, publishers with less than $1 million USD of publishing revenue rarely have the highest level of robust digital preservation.

A significant portion, approximately 28%, of academic journal articles with DOIs appear entirely unpreserved

So, what can we conclude from this work? In 2005, almost two decades ago, Don Waters, the Senior Program Officer for Scholarly Communications at the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation edited a consensus statement in the Association of Research Libraries newsletter, titled ‘Urgent Action Needed to Preserve Scholarly Electronic Journals’. Many of the calls in that piece were heeded; we have archives that can provide the minimum level of service described therein and a comprehensive persistent identifier scheme on top of this. Recent efforts such as Project JASPER have also highlighted the importance of preservation in the brave new world of open-access publishing.

However, as our study shows, the state of digital preservation of serials remains fragile in 2024 and these calls have not fully been answered. A significant portion, approximately 28%, of academic journal articles with DOIs appear entirely unpreserved, endangering both persistent identifier systems and the chain of verifiable citation that they are meant to underwrite. This confirms the findings of other studies that have examined the disappearance of OA journals. It is also, of course, a problem not confined merely to academic journals; the digital preservation of all electronic resources poses challenges. Availability of material, the aspect of preservation studied in this article, is also not the be-all and end-all. Other preservation concerns include the very real threat of format obsolescence, as just one example. Indeed, digital preservation is an ongoing activity, not a one-time deposit that requires constant re-investment and reinvention. In the coming years, the importance of considering, also, the environmental impacts of preservation strategies will be of import.

While preservation deficits are not likely to be resolved in the very near future, taking action now will improve the situation and help to safeguard the digital scholarly record.

This post draws on the authors article, Digital Scholarly Journals Are Poorly Preserved: A Study of 7 Million Articles’, published in the Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Maxence Pira via Unsplash.

The problem is, that you have to pay for these services, as our journal does for Crossref as well. Since we have published an independent journal in social sciences hosted by a university library since 1994 with no budget whatsoever, we are reliant on our library host in the US for Portico. Good job the 700 or so articles are also on my cloud and laptop. And Wayback Machine of course.