Asia may be thriving, but it still faces real economic constraints and governance challenges. Danny Quah argues that the region needs to be understood as a whole if these issues are to be addressed.

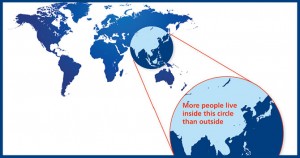

Two-thirds of humanity is Asian. This includes the populations of not just the world’s only two-billion-people economies – China and India – but also tiny nation-states like Singapore, Bhutan and Mongolia.

As Asia is large and diverse, integrated thinking on its economic development is difficult and relatively scarce. At the same time, the continent faces both risks and opportunities that are common across its constituent nation-states. Many of these challenges can be effectively addressed only through joint effort, open discussion and co-ordinated diplomacy – and so require a shared understanding of the forces driving those risks and opportunities.

It is Asia that in the last 30 years has forced the world’s economic centre of gravity to arc 5,000km east across the surface of our planet. It is Asia’s developing economies that, over the course of the global financial crisis, accounted for 42 per cent of the world’s economic growth, six and a half times that contributed by the Transatlantic Axis (the US and the EU).

Despite all this, Asia is underdeveloped. Its economies remain, in the eyes of many, rife with imminent “growth slowdowns” and “middle-income traps”. Natural resources are in short supply. From China to Singapore, an ageing population haunts. Asia’s economies are unbalanced, with excessive reliance on exporting to the developed West. Domestic consumption is too low, savings and accumulation too high.

These economic difficulties are daunting enough. But, in addition, problems of governance figure prominently. Asia’s largest economy eschews the ballot box; others that don’t are nonetheless not the politically freest of societies. Can free-wheeling innovation take place without inviolate rights over private property, widespread public participation in the political process, a free press and indeed liberal democracy?

Lacking good institutions, Asia stuffs itself full of bad ones: entrenched extractive elites, corrupt public procurement, government bureaucracies serving not the public but themselves. These are, by their nature, difficult to document, not least when the behaviours in question are criminal.

But bad news can be overplayed. To understand Asia’s situation properly one needs to contextualise: compare bad news here to developments elsewhere in the world or set them against a more complete background of Asia’s ongoing evolution.

Consider democratisation. A 2012 BBC report asked: for China’s continued success, does it – and by implication the rest of Asia – have to become more like the West? The suggestion was that democratisation was required for success. What matters, though, is delivery, not form. Ballot-box electoral competition is a commendable mechanism, but it is not uniquely successful, either in theory or in practice. Its critics might even debate whether democracy in the real world is the success it claims to be. They can point to the institution of gerrymandering in the US; the growing separation in the EU between political elites and those they represent; and the legitimacy of political mandate when narrow electoral outcomes lead to large divergence in policies – as occurred egregiously but not uniquely in the 2000 US presidential race.

On delivery, the comparison between China and India is a natural one, although it is obviously a comparison that is nuanced and can be overdone. India is the world’s largest democracy; China, the world’s largest non-democracy. China lifted 627 million citizens out of extreme poverty between 1980 and 2005; India increased the number of its citizens in extreme poverty from 420 to 460 million. Obviously, much, much more was going on in China and India than just varied forms of political leadership. Those other differences help explain these disparities in growth and poverty reduction. But that is the point: everything else mattered; everything else will always matter.

The Pew Global Attitudes Project annually asks citizens in different countries if they feel their nation’s political leadership is moving the country in the right direction: since 2008, the fraction of China’s citizens agreeing has never dipped below 85 per cent; in the US, that fraction has never risen above 36 per cent. Even adjusting these numbers for plausible biases, no clear evidence emerges that political legitimacy comes from form rather than from delivery.

Certainly, ordinary citizens in Asia are dissatisfied with the low level of public service provision they get. They are properly irate when they find entrenched elites unaccountably doing much better than themselves. But they also know that leading economists have for years described how in the US real wages for the median worker have been falling steadily since the late 1970s, even as the 20th century saw the US economy lead the world in overall economic performance. And they have read media accounts of how the richest 1 per cent in the US own more than 90 per cent of the rest of the population.

Extractive elites, corporate malfeasance, lower-income classes falling ever further behind? These are problems everywhere – in democracies and non-democracies alike. Many other bad-news conventional wisdoms on Asia’s growth are, in my view, similarly more intricate than they at first seem. The dangers of Asia’s ageing population need to be seen against a background of risks from social instability generally. Populations rise in protest if their economic expectations are higher than reality delivers. Over the next decade the Middle East will have 100 million more young people, from an ongoing demographic boom. The region’s youth unemployment rates are the highest in the world. Which is worse for social stability (and thus growth): 340 million old people practising taiji in the park or 100 million angry young people facing no gainful employment?

Turn finally to international trade. Yes, Asia exports a great deal to the advanced economies. Those exports now exceed 10 per cent of total world exports, up from 6 per cent in the 1990s. But the fact is that Asia simply exports a lot to everyone. As a fraction of its total exports, China’s exports to advanced economies have, since the 1990s, fallen more than 10 percentage points.

In 2011 the German Marshall Foundation asked people what part of the world they considered most important for their national interest. Among Americans aged 18-24, over 75 per cent answered Asia; of Europeans, almost uniformly across all age groups, 40 per cent said Asia. But more interestingly, 63 per cent of Americans said they considered the rise of the East a threat, double the proportion that consider it an opportunity.

Asia has a problem. Many in the advanced economies have as their primary concern the belief that the rise of the East will take away Western jobs and prosperity. The US is extreme on this, but it is not alone. Asia has spent no time explaining to the West its intentions, nor the reality of its patterns of trade.

What has emerged is a cauldron of international tensions, driven by misunderstanding. What goes relatively unnoticed is that Asia’s continued growth implies a profound international power shift, and that the needed adjustments in global governance are not in place. Each country in Asia is obviously different; each needs to adjust to a different set of circumstances as development unfolds. Nonetheless, as a group Asia’s sovereign states share common problems in this global transformation: the challenges on global leadership and legitimacy will require a unified response.

Danny Quah is Professor of Economics and International Development and Kuwait Professor at LSE

This article was re-posted from the LSE alumni magazine. You can view the original here.

Related Posts

|

Wow! After all I got a blog from where I be able to actually take valuable information concerning my study and knowledge.