Danny Quah says China can provide a new narrative to lead, without even needing to mention power.

China’s currency recalibrations have jolted global markets, as did America’s 2013 “taper tantrum”, when then US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke said the fed might slow the rate of bond purchases.

China is seeking inclusion of its currency in the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights on the way not only to renminbi internationalisation, but also to challenging the US dollar as world reserve currency. As if this weren’t enough, China has also set up the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and was key in putting together the BRICS development bank.

Taken together, these reflect the largest disruption yet to an international financial architecture in place since the early 1950s. Yet again, China’s rising power is plain.

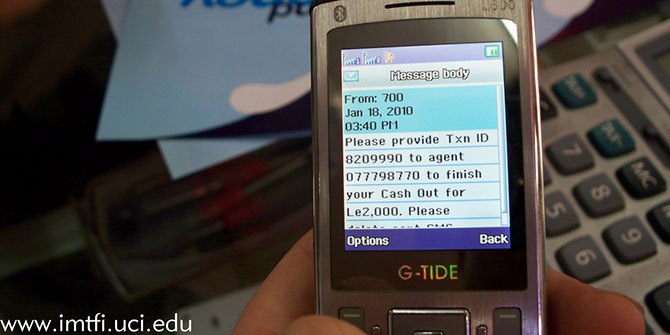

[jwplayer mediaid=”2443″]

LSE’s Danny Quah discusses the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank on the BBC.

For some observers, this sets off alarm bells, and they are puzzled why the rest of the world isn’t more concerned: “China’s rise directly challenges America. Competition between the two is inevitable. Just as America dominates the Western Hemisphere, China will aim to dominate Asia, and America and China will each seek to contain the other. As China continues its ascent, the likelihood of war with America only ever grows.”

Such observers are not unique to one side or the other, but include both Chinese – Yan Xuetong – and American (John Mearsheimer) writers, and I paraphrase them, but only just.

Whatever idealists might suggest, a battle for world leadership is set and has been in train for a while.

In his book Is the American Century Over?, Joseph Nye described how the “American century” emerged in the 1940s partly from its unique capacity to provide the global public goods the world needed. Nye masterfully showed us the devastating reach of his concept of soft power: that influence is more important than military power and that domination doesn’t mean leadership. He reminded us how Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew had once told him that America would always be ahead of China: while China might boast a population of 1.3 billion people, America could draw on the talents and goodwill of more than seven billion.

But, in opposition to Nye’s argument, that capacity to provide the world its global public goods is no longer unique to the US, nor is it obviously America’s to wield. The world’s economic centre of gravity used to sit off the eastern seaboard of the US, but no longer. Many of the world’s problems require global cooperation: no single nation by itself, certainly not the US, can take on the problem of global climate change, cybersecurity or international pandemics. That unique capacity that started the American century is no more. If the century is to remain American, the US will have to be a genuine leader, not just a unilateral doer.

America faces two options. It can lead the world by insisting it wields fearsome power – in its military, in its technology, in the strength of its economy, in its ownership of the world’s reserve currency, in its creativity and in the Nobel prizes it wins.

Or it can lead the world by being a force for good.

Time was, it did both power and legitimacy. But if the US now wields only the first – as Nye describes so convincingly – can it still draw on the goodwill of the seven billion people on earth that Lee Kuan Yew promised? Without conviction and clarity on the global public goods it delivers, is US soft power only ordinary power?

The idea is neither fanciful nor whimsical that leadership comes with doing good for those who are led. It is, after all, a principle of economics that under free-market capitalism the only need a society has for government is when government provides public goods. Democracy has as one of its most cherished principles that a society should select leaders who are accountable, competent and effective, and who work for that society. The phrase “consent of the governed” shines a light in the second paragraph of the American Declaration of Independence. True, the community of nations has no world government, and the people in those nations are certainly not citizens of the United States. But if America does not seek their consent, perhaps neither should it seek to lead them.

Conversely, China can provide a new narrative to lead the world, one available to it without even needing to mention power. With the AIIB helping build infrastructure in energy, telecoms and transport throughout Asia, China can just say: “We are far from perfect. But we understand how hard it is to develop and grow an economy. We don’t always get it right, and we might certainly not get it right for you. But we’re here to help.” China has reached out with AIIB, the BRICS development bank and a host of other initiatives.

The AIIB’s balance sheet, while substantial, pales compared with those of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank; it is even smaller than the Asian Development Bank’s. This is no China machine out to conquer the global economy through sheer power. This is building an inclusive international order, the same thing America had done. This narrative could well end up winning over the world’s people who don’t live along the transatlantic axis, and who never quite got to be part of the American century.

In contrast, many accounts of the American century now sound as if they rely more on America’s power, and less on America’s doing good in the world.

If we continue down this road and apply the Nye-Lee Kuan Yew criterion, China is going to win. What’s at stake? That which Lee Kuan Yew promised: the talents and goodwill of the planet’s seven billion people.

Danny Quah is Professor of Economics and International Development, and Director of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre at the London School of Economics. This article was originally published as ‘How China’s rise is revealing the cracks in US claims to legitimacy as global leader’ in the South China Morning Post.

Related Posts

|