By Shalini Unnikrishnan and Juliet Bedford

The adoption of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will likely have the same galvanising effect as the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 15 years ago. They will focus the world’s attention on the great economic, social, and humanitarian needs of our time.

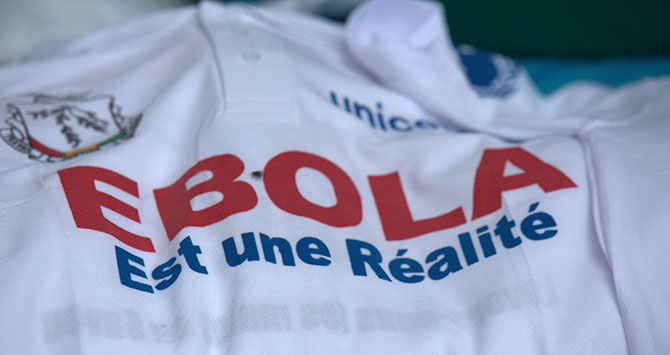

If we face a major health crisis on the scale of the recent Ebola epidemic, however, many of the U.N.’s development priorities could fall by the wayside. The only way to avoid this is to change the way the global health community will respond—and change it now. Another flawed effort is not something we can afford with so many challenges remaining and so many lives at risk.

We’ve seen what happens when things go wrong. Lives are lost. Progress is rolled back.

Make no mistake: the MDGs brought about huge improvements in the health and living conditions of millions of people. As a result of this global effort, U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon was able to report that the number of individuals living in extreme poverty has been reduced by 700 million; millions fewer are dying each year from malaria and tuberculosis; and “the likelihood of a child dying before age five” has been reduced by nearly one half.

These are huge accomplishments.

Still, a global health emergency or pandemic has the potential to set back or derail the new effort. As the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Ebola assessment panel, chaired by Dame Barbara Stocking, noted recently, the response to the outbreak was late and ineffective. WHO and the global health community were unprepared, and there was poor coordination and collaboration.

We saw a systemic misunderstanding of the role local communities play in spreading—and even more importantly, in stopping—disease, particularly Ebola. We were both on the ground in West Africa working as part of the international response, so we can speak personally and directly to this point.

For too long, the response was “virus centric,” focused on getting resources and technical solutions in place. It was only when the response also became “people focused”—understanding and adapting to the influences of culture, beliefs, and practices—that Ebola began to be brought under control and communities became more likely to accept the response. People alerted the authorities when someone fell sick or had died. Where we listened, communities gave us direction. They asked that we use white rather than black body bags to respect their customs; they asked for the ambulance sirens to be turned off to reduce attention and stigma; they asked for burial teams to include local community members who they knew and trusted.

Yes, the international health response was late, despite the efforts of Médecins Sans Frontières to raise the alarm sooner. But its effectiveness was further reduced when we did not fully consider the socio-cultural context of the people affected and when we did not involve them in the response. The results are there for all to see.

For the three most affected countries, the human cost has been devastating. More than 11,000 people have died, including over 800 health staff. More than 16,000 children have been orphaned. Families, communities, and villages were torn apart. Schools shut down for months. Children’s vaccination programmes were curtailed. Money intended for health and development initiatives were diverted

GDP growth in Sierra Leone fell to 4% last year, down from a pre-crisis projection of 11.3% for the year. Guinea and Liberia were similarly hit. Moreover, as the World Bank has noted, “Associated aversion behavior” – meaning fear of another, wider outbreak – has shaken consumer and investor confidence throughout Africa.

The shortcomings of the Ebola response are being analysed by the Secretary-General’s “High Level Panel on the Global Response to Health Crises” and the “Global Health Risk Framework Initiative,” an international undertaking coordinated by the U.S. National Academy of Medicine. Yet, as the U.N. prepares to introduce the SDGs, a new human crisis is sweeping across the Mediterranean, as thousands of displaced persons seek refuge in Europe. The new goals will need to operate and succeed in increasingly challenging contexts like these.

Ebola tested the world’s ability to address health crises, and the world cannot afford to fail in the future. If we want the SDGs to have as great an impact as the MDGs, we need to develop and test new frameworks of global public health that incorporate communities as active participants in both preparedness and response. When the next pandemic occurs, we need to be ready.

About the authors

Shalini Unnikrishnan (left) is a Principal at The Boston Consulting Group. She provided on-the-ground support in the creation of UNMEER.

Dr Juliet Bedford (right) is the Founder and Director of Anthrologica, a research-based organisation specialising in applied anthropology in global health. She served as the lead anthropologist for the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER).

About the MSc International Development & Humanitarian Emergencies

Related Posts

|