Up to 90% of the world’s reefs will be at risk of coral bleaching by 2030, according to ODI research. Thomas Aedy (MSc IDHE, 2014-16), one of the authors of ODI’s recent flagship report Projecting progress: reaching the SDGs by 2030, assesses the causes of this decline and says new approaches are needed to address the issue. (Originally posted at DevelopmentProgress.org.)

That reefs are under threat has become a well-worn fact. Less well-known is the severity of this threat – and its cost. ODI projects that, by 2030, as much as 90% of the world’s reefs will be at risk of coral bleaching. Unless compelling action is undertaken – urgently – we stand a good chance of losing a significant share of today’s reef cover. This blog sets out the multiple stressors faced by reefs, the costs of inaction, and the reasons why our current approach to marine health simply cannot work.

In a new piece of research, ODI has drawn up and compiled projections for each of the 17 SDGs that will be agreed in New York later this month, to examine where the world – on its current trajectory – will stand by 2030 on each goal. This blog looks at the projections for SDG 14: the marine goal. That goal calls on states to conserve and sustainably use our oceans, seas and marine resources. On the basis of the critical value of reefs to sustainably preserving marine life, ODI shines the spotlight on Target 14.2 (which demands that marine and coastal ecosystems be sustainably managed). It uses projections compiled by the World Resources Institute (WRI) for the proportion of reefs that will be ‘at threat’ by 2030 (if current trends continue).

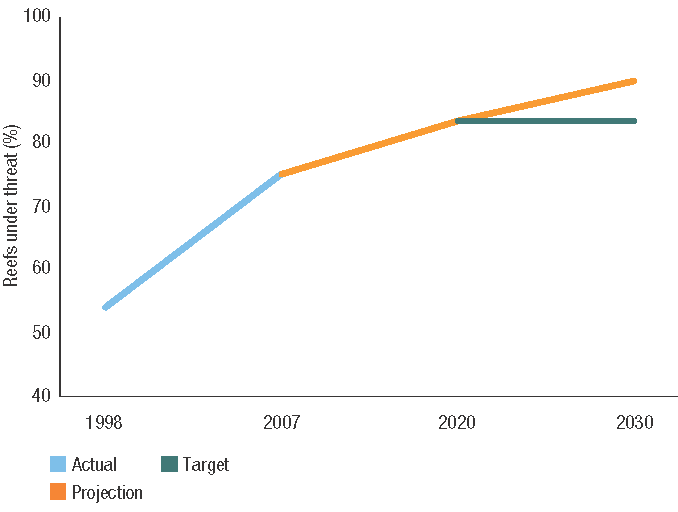

Setting these projections against Target 14.2, ODI awards the world on ‘F’-grade on SDG 14 – the lowest on offer. Why? In order to meet Target 14.2 by 2020, the proportion of reefs at threat globally would have to be falling by then – the target states that coastal ecosystems must be protected from significant adverse impacts by 2020. Since our projections show that the proportion of reefs under threat is actually set to increase past 2020, the trajectory is heading in the wrong direction – earning SDG 14 its disappointing ‘F’-grade.

How reefs become extinct

Pressure on reefs is global and local. One quarter of the carbon emitted into the atmosphere gets absorbed by our oceans, increasing surface-seawater temperatures and ocean acidification. Each of these threatens coral life: elevated temperatures disrupt the symbiosis between corals and the marine plankton they depend on, while acidification reduces the rate at which corals calcify their skeletons. Local pressures also matter. Marine-based pollution, watershed pollution, destructive fishing practices and coastal development all constitute local risk factors.

Alarming Projections

WRI combines all of these pressures to form a ‘threat’ index for the world’s reefs – and projects how this will change in the future. The story is sobering indeed. To get an idea of how WRI comes to a measure of ‘threat’, see the report here.

Take a look at the graph below for a snapshot of the severity of the problem. Two headline lessons stand out.

Firstly, the deplorable state of reef health today: as much as 75% of our reefs are currently ‘at threat’ of bleaching. This is no idle threat. Much of our coral life has already been lost. A startling 80% of the Caribbean’s coral reef cover is estimated to have been lost over the last 50 years – largely as a result coastal development and pollution. It is estimated that between 40 and 50% of corals worldwide have been lost over the same period (data on historical coral degradation is being collected by the Catlin Seaview Survey and can be accessed here). Current early warning signs of an El Niño event next year have led the US National Oceanic & Atmospheric Association (NOAA) to predict a major global bleaching event that will impact approximately 38% of the world’s corals by the end of this year.

Secondly, pressure on reefs is set to climb, with 90% of reefs threatened by 2030. From a poor starting-point, the trend line is going in the wrong direction.

Why should we care?

There are two reasons the international community should pay special attention to the degradation of our reefs.

Firstly, their erosion comes at considerable environmental and economic cost. Despite covering just 0.1% of the ocean floor, reefs carry an estimated 25% of all known marine life and play a significant role in marine food chains. Over 275m people live within 30km of reefs, who rely on them for food, tourism and coastal protection. By one estimate, halving global coral loss by 2030 would provide economic benefits worth £46 billion to the international community, at a cost of just £1.9 billion.

Secondly, this degradation will take considerable time to reverse. Water has a high specific heat capacity, which means it takes a long time for it to dissipate energy. Even if the international community were to make significant – and timely – strides in combatting carbon emissions, the rate of reduction in surface-seawater temperatures would lag those in the upper atmosphere. The longer we wait on climate change, the harder it will be for coastal ecosystems to recover.

Why Our Current Approach Won’t Work

The world has not been blind to the state of our reefs. But its response has been ineffective. In Nagoya in 2010, world leaders made a commitment to legally protect at least 10% of their coastal areas, but we can’t protect our reefs from climate change by marking out this 10% or that 10% out for special protection. Global problems need global solutions.

Leaders paid lip service to this need at the 2010 Nagoya conference by including a woolly commitment to ‘minimise’ anthropogenic pressures on corals, but vague aspirations won’t be enough to tackle the climate change issue. That’s why an ambitious deal in Paris in December with clear, concrete targets is critical to stimulate the urgent action needed on emissions – and save what’s left of our fragile reefs.

About the MSc International Development & Humanitarian Emergencies

Related Posts

|