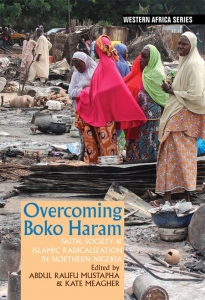

Dr Kate Meagher tells us about Overcoming Boko Haram: Faith, Society and Islamic Radicalization in Northern Nigeria, a book she recently co-edited with the late Abdul Raufu Mustapha, that digs into the underlying causes of violent Islamic radicalisation in Northern Nigeria.

The rise of violent Islamic extremism in West Africa over the past decade took everyone by surprise. Terrorist outbreaks in north-eastern Nigeria from 2009, and in northern Mali from 2012, compounded by worrying extremist attacks in central Niger and northern Burkina Faso in recent years, has alarmed policy makers as well as local populations. It has also called into question pervasive assumptions about the peaceful nature of West African Islam. Scholars as well as officials have long celebrated the tolerance and non-violence of Sufi forms of Islam prevalent in West Africa, and some have even promoted West African Sufism as a secret weapon against extremism. Yet neither tolerant Sufi ideologies nor international initiatives and military missions have been able to contain the surge of Islamic extremism across the region.

After a decade of escalating extremism across the West African Sahel, a recent OECD paper declared that little is known about what is driving the spread of Islamist violence. Some blame the rise of extremism on corruption within West African societies, while others call attention to the rise of Salafism, a more fundamentalist form of Islam emanating from Saudi Arabia that is disrupting the hold of traditional Sufi Islam. The menu of solutions continues to focus heavily on securitization, anti-corruption measures, and promoting ‘safe sects’ in West African Islam. What is most surprising is the remarkable lack of focus on crippling levels of poverty and inequality in what is recognized as one of the poorest parts of the world. Overcoming extremism in West Africa means confronting not only poverty and environmental stress, but the damaging role of market reforms in a region where unfamiliar cultural values and low levels of education have made the bulk of society unattractive to market-based forms of inclusion.

A new book edited by Abdul Raufu Mustapha and Kate Meagher, Overcoming Boko Haram: Faith, Society and Islamic Radicalization in Northern Nigeria digs into the underlying causes of violent Islamic radicalization so as to chart a more effective path through the crisis. It is the third book in a trilogy on religious conflict in northern Nigeria (Sects and Social Disorder, and Creed and Grievance), coordinated by the late Abdul Raufu Mustapha. Overcoming Boko Haram examines the social and political forces surrounding the rise and persistence of the northern Nigerian Islamist sect widely known as Boko Haram, identified by the Global Terrorism Index in 2015 as the world’s most deadly terrorist group. While there has been a profusion of publications exploring the ravages of Boko Haram, this book looks beyond the shock factors to examine the actual drivers of Islamic extremism in northern Nigeria, and to identify counterforces with a potential to reign in the insurgency.

The book starts from the observation that Boko Haram is a homegrown terrorist group in a society where the vast majority of Muslims do not support violent extremism. The group’s occasional connections with Al-Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM) or ISIS were largely to enhance their terrorist credentials rather than fundamental organizational linkages. Yet Boko Haram has little support at home either. A survey by the Pew Research Centre showed that 94% of Nigerian Muslims express a negative view of Boko Haram. In fact, northern Nigerian civil society has been a key source of resistance to Boko Haram, including the Civilian Joint Task Force (CJTF) who drove Boko Haram out of Maiduguri in 2013; the Bring Back Our Girls campaign which has an active northern Nigerian membership; and numerous local civil society groups and NGOs that promote youth education, foster local enterprise, and support widows and orphans to keep the poor and disaffected out of the grasp of Boko Haram. While current stereotypes represent Muslim societies as the problem, citing violent religious ideologies and oppressive attitudes to women, this book shows that northern Nigerian society can be part of the solution.

Overcoming Boko Haram makes three broad arguments. The first is that Islamic extremism in Nigeria is not primarily about religion. It is not a product of global terrorist networks or violent religious ideologies, but of domestic political and economic forces. Secondly, understanding Boko Haram requires that we look beyond the activities of jihadis to the wider social processes and pressures that led the insurgency to emerge where and when it did. It is significant that Boko Haram emerged in the comparatively quiet and remote area of Borno State in the far north-east of the country, rather than in Muslim majority areas in south-western Nigeria, or in the much poorer Muslim society of Niger, just across Nigeria’s northern border. Equally telling, the group emerged in Borno State where Islamic practice is known for a wealth of traditional innovations, rather than in the epicentre of fundamentalist Salafi revivalism in the north-western Nigerian city of Kano.

Thirdly, the book challenges the contention that poverty is not a central factor in the rise of Boko Haram. International scholars, public personalities and even the previous Nigerian president have persistently dismissed the idea that Boko Haram is a response to poverty. Some argue that many Boko Haram members are not poor, while others contend that many who are poor did not join Boko Haram. But poverty is not just about individual deprivation. It involves a sense of group marginalization and economic inequality that is as much about macro-economic disparities as about individual experiences of want. Attention to regional macro-economic indicators puts the realities of poverty and inequality in stark relief. While the Human Development Index (HDI) in southwestern Nigeria is similar to that of India, the HDI in northern Nigeria is lower than that of Afghanistan, and Nigeria’s North East shows particularly high levels of economic and infrastructural deprivation.

Looking beyond Muslim stereotypes, armchair ‘Boko Haramology’, and economic myopia, Overcoming Boko Haram offers an inside analysis of the factors shaping radicalization and counter-radicalization within Nigerian Muslim society. Based on extensive fieldwork by regional specialists, the book traces the complex causes of violent radicalization. The loss of livelihoods created by the drying up of Lake Chad in northern of Borno State is a factor, as are cycles of political and military corruption that have turned the insurgency into a cash machine for politicians and the military, undermining incentives to end the conflict. The role of Salafism is also key, but not quite as assumed. Salafism has introduced a more modernist, pro-education, gender-friendly form of Islam, but it has also stirred up religious frictions and recklessness in competition for followers. Aggressive religious fragmentation has distracted attention from the doctrines of tolerance and moderation that course through West African Islam, and the potentially moderating role of the bulk of clerics, both Sufi and Salafi. The book also examines the radicalizing and counter-radicalizing dynamics of northern Nigerian youth, women and the informal economy, and the sobering endgames of current approaches to the insurgency.

Overcoming Boko Haram calls for ‘whole of society’ solutions to the insurgency, based on a ‘whole of society’ understanding of the conflict. This involves getting Nigerian and international policy makers to face their own demons: corruption, and the broken promises of liberal modernity and market reforms, and counter-terrorism protocols that are inappropriate to the realities of Muslim majority societies. More socially-grounded policy thinking offers a new way forward based on evidence rather than Islamophobia. Policy alternatives include appropriate regulation rather than securitization of religion; job creation programmes centred on the needs of northern Nigerian youth rather than foreign investors, and socially appropriate paths of gender empowerment rather than imposing Western gender norms. While appropriate military measures are required to end the insurgency, the importance of more inclusive statecraft and economic policy cannot be over-emphasized. It is not Islamic ideologies that have produced the tinderbox of extremism, but narrow market ideologies that have pushed the disaffected to desperation. In Nigeria and across the globe, the rising tide of right wing populism and violent social protest is revealing the cost of political and economic systems that leave too many behind. The time has come to address the real issues.

Last edit of article: 12:32, 22/01/2020

Kate Meagher is Associate Professor in Development Studies, London School of Economics. Her books include Identity Economics: Social Networks and the Informal Economy in Nigeria (2010), and, edited with Laura Mann and Maxim Bolt Globalisation, Economic Inclusion and African Workers: Making the Right Connections (2018).

A longer version of this article was originally written for the Proofed.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

No body else will ever over come Islamic extremism in Northern Nigeria, not even the world over except the Islamic faithful themselves, as extremism is a tradition of the religion itself. The Nigeria government knows it and the world over knows it even better. While the extremists see themselves performing their just rituals, their big wings who benefit from this endless tussle of acclaimed faith see it business as usual. So if destruction of innocent lives and property is bad in the eye of Islam, let them make amends for general peaceful co-existence, period.

It is odd that people tend to hold all Muslims responsible for acts of Islamic extremism, but no one would think it reasonable to hold all Christians responsible for the Ku Klux Klan. Extremists do not define or represent a religion, they signal underlying political, economic and social problems. Until people focus on understanding and addressing the underlying issues rather than blaming religious ideologies held by a peaceful majority, Boko Haram will rage on. These are the options — take your pick.

I am trying to contact you re this publication and the previous one, “Creed and Grievance” , I tried emailing you but they bounce back. I tried through Dipa Patel and the lse mail system but still silence. I spent 35 years in Northern Nigeria and was a friend of the late Prof Raufu Mustapha. I look forward to hearing from you. Congratulations on your publications.

I have responded to your message. Please check your Gmail inbox.

Islam condemns all forms of extremism from anybody and is about finding inner peace and spreading outer peace to all humanity

Here’s a great resource to learn more about it

https://www.alislam.org/articles/islam-and-terrorism/