Professor in Practice and Senior Strategic Adviser at Oxfam GB, Duncan Green, invites comments on his paper exploring Covid-19 as a critical juncture.

My LSE students are a challenging lot (not as in ‘problem’; as in ‘challenging’) and their questions got me thinking about Covid-19 as a critical juncture. The result is this short-ish (12 page) paper (much improved by the students’ comments on earlier drafts). Please send comments. We will also be discussing it on Zoom next Wednesday (8th April) 2.30-3.30pm UK time, if you’re interested.

The meeting details are the following:

LINK TO JOIN ON ZOOM

(you’ll need to download Zoom if you don’t have it)

Meeting ID: 539 628 797

Password: Juncture

Below are some extracts (only a fraction of the paper, so please don’t say ‘you haven’t discussed X’ without checking the full version!):

‘Critical Junctures’ are the scandals, crises or conflicts that can throw the status quo and power relations into the air, opening the door to previously unthinkable reforms. In Plagues and the Paradox of Progress, Thomas Bollyky argues that such events include health shocks: ‘Encounters with infectious disease have played a key role in the evolution of cities, the expansion of trade routes, the conduct of war and participation in pilgrimages.’

So what might be the longer term impacts of Covid-19?

Politics

Covid-19 shines an unforgiving light on all political leaders and systems, exposing their strengths and weaknesses in preparing, detecting, responding and (eventually) leading the recovery from a crisis.

At a national level, Nic Cheeseman sees three different mechanisms through which Covid undermines democracy:

‘Authoritarian leaders use COVID19 to ban rallies and protests, and in some cases cancel elections, eg by declaring states of emergency.

Less obviously, authoritarian leaders simply do more of what they have always been doing in the knowledge that no one is paying attention.

The third mechanism is more universal and less intentional, at least in the short term. The assumption of emergency powers by governments creates long-term problems because these powers – and the new technologies developed to respond to crises – are rarely fully reversed when the crisis is over. This is the ‘ratchet effect’ and it is far more insidious.’

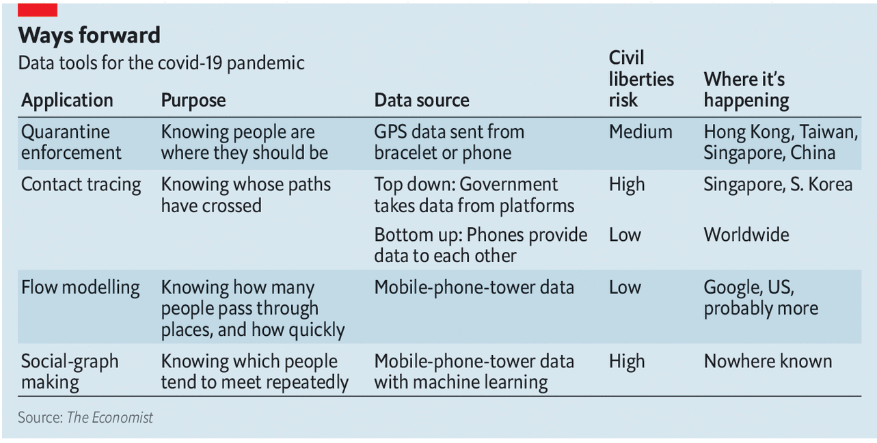

Nowhere has the encroachment on democratic and civic space been more apparent than over the issue of surveillance. Data protection has been swept aside in many countries in the interests of tracking and containing the pandemic (see Economist summary table).

Society

Social norms – the expectations that guide assumptions and behaviour about how we relate and treat our fellows, can change in the aftermath of a CJ.

Gender: The crisis is heavily gendered, both in impact and response. Women comprise the majority of health and social care workers and are on the front lines of the fight against COVID-19. Mass school closures have particularly affected women because they still bear much of the responsibility for childcare. Women already do three-times more unpaid care work than men – and caring for relatives with the virus adds to the burden. In many developing countries, the informal economy (often predominantly female) is receiving much less state attention than waged work. There is a clear risk of increased violence against women as a result of self-isolation.

What is not yet clear is whether this will lead to longer term rethinking of, for example, the importance and policy priority given to the care economy. World War One was followed by an upsurge in women’s emancipation, whereas after World War Two, women were driven out of the workforce and back into the home. Which will it be this time?

Solidarity: The extraordinary mutual aid response and explosion of volunteering in many countries could be a turning point in many people’s relationship with their communities and with politics. Once the virus is defeated, some will probably morph into social movements, perhaps in the way that the civic action in response to Mexico’s 1985 earthquake sowed the seeds for new social movements that ultimately led to the overthrow of Mexico’s one party state.

Space as a Human Right: At a personal level, the sudden limitation/removal of public space through lockdown makes us acutely conscious of space as a public good. Will the crisis lead to new priority and attention being given to the right to space?

The Economy

The Economist believes that ‘the world is in the early stages of a revolution in economic policymaking.’ Austerity has gone out the window; ‘whatever it takes’ is on the lips of the world’s leaders. It even sees a possible knock-on effect: ‘If central banks promised to fund the government during the coronavirus pandemic, they might ask, then why shouldn’t they also fund it to launch an expensive war against a foreign enemy or to invest in a Green New Deal?’

This may of course be wishful thinking – magic money trees abounded during the global financial crisis, but rapidly disappeared in the upsurge of austerity that followed.

The impact on low and middle income countries has received less media attention in the North. By 28th March, foreign investors had pulled $83bn out of emerging markets since the start of the crisis, the largest capital outflow ever recorded. Remittances from migrant workers – often a crucial lifeline that globally comes to four times the volume of aid – are also bound to fall.

What does this mean for Aid?

Aid agencies will be forced to respond to what could become an extraordinary humanitarian situation – imagine the impact of Coronavirus running riot in overcrowded refugee camps with few facilities – and also to maintain work on existing priorities. Where will the money come from? A survey by the New Humanitarian concluded ‘attention and resources could shift away from some of the world’s most vulnerable populations even as COVID-19 presents a new threat to them.’

In the short and medium-term, there will be a desperate need for debt relief that by one estimate could free up $50bn over the next two years. In the longer term, development cooperation will have to play its part in ensuring that the post-Covid recovery ‘leaves no-one behind’, for example by addressing the generational damage caused by the lockdown of most of the world’s schools.

Some Implications for Advocacy and Campaigns

Advocacy around the pandemic is likely to follow a sequence:

- Advocacy bearing witness to the impact of the pandemic, especially on vulnerable/forgotten populations (eg shanty towns, prisons)

- Advocacy for particular policy responses, such as debt relief, or safety nets for those in the informal economy

- Advocacy to address the unintended negative consequences of the responses.

- Advocacy to shape the priorities of subsequent recovery policies.

The tone and content of advocacy and campaigns will need to adapt to where we are in that sequence – business as usual is neither wise, nor feasible.

Tone: At a time when the public is anxious, scared, and in need of comfort, I am startled by how much of the advocacy I see on my timeline retains its pre-crisis angry, finger-wagging tone. All too often, the general message seems to be ‘we were right before; now because of the virus, we are even righter. Why aren’t you listening? You must be stupid and/or evil.’

Content: What will emerge in the medium/long term is unpredictable, and activists will need to ‘dance with the system’ as it changes around them:

- Some existing advocacy priorities will become less salient – a real challenge to organizations where advocates become deeply identified with ‘their’ issue.

- Some advocacy priorities will become more relevant and powerful, provided they can be convincingly linked to the crisis (see the gender-based violence example, or the importance of the care economy).

- But new issues will also emerge, like the earlier discussion on space as a human right.

- New threats will also appear, as what Naomi Klein dubbed ‘disaster capitalists’ seize on the crisis as window of opportunity. Defensive strategies – stopping bad stuff from happening – are likely to be needed.

Final Thoughts

Stepping back from the detail, I am struck by the gulf between the discussion in governments such as the UK and US, and the response from the ground. At the level of national leadership, the moment feels more like World War One – a crisis that bequeaths a legacy of suspicion and non-cooperation for years or decades to come, sowing the seeds of future crises. But in the streets and communities, the upsurge in solidarity and compassion feels much more World War Two, a moment of courage and creativity, of new forms of human organization emerging to make the world a better place.

The question for advocates and campaigners then becomes how do we enable that World War Two spirit and commitment to find rapid and lasting political expression?

If there is one message from this paper it is that advocates and campaigners, fired up by what Martin Luther King called ‘the fierce urgency of now’ must embrace, study and understand that history in order to shape it. Because it is a history that is being written right now, by all of us.

Dr Duncan Green is Senior Strategic Adviser at Oxfam GB, Professor in Practice in International Development at the LSE. His daily development blog can be found on www.oxfamblogs.org/fp2p/.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.