Between 2000 and 2010, several important demographic shifts occurred amongst female migrants in Ghana. Using primary and secondary data, Dr. Samantha Lattof, Professor Ernestina Coast, Professor Tiziana Leone, and Dr. Philomena Nyarko discuss the increase in internal migration among young, unmarried women and how economic opportunity drives contemporary female migration in Ghana.

Historically, migration-related employment amongst girls and women was invisible or under recognised, with girls and women written off as ‘passive’ migrants accompanying spouses or parents or labelled as ‘dependent’ (i.e., migrating as wives). Such labels—absent from the literature on migrant men and boys who are not classified according to their relationship status—overlook the many forms of migrant women’s economic labour.

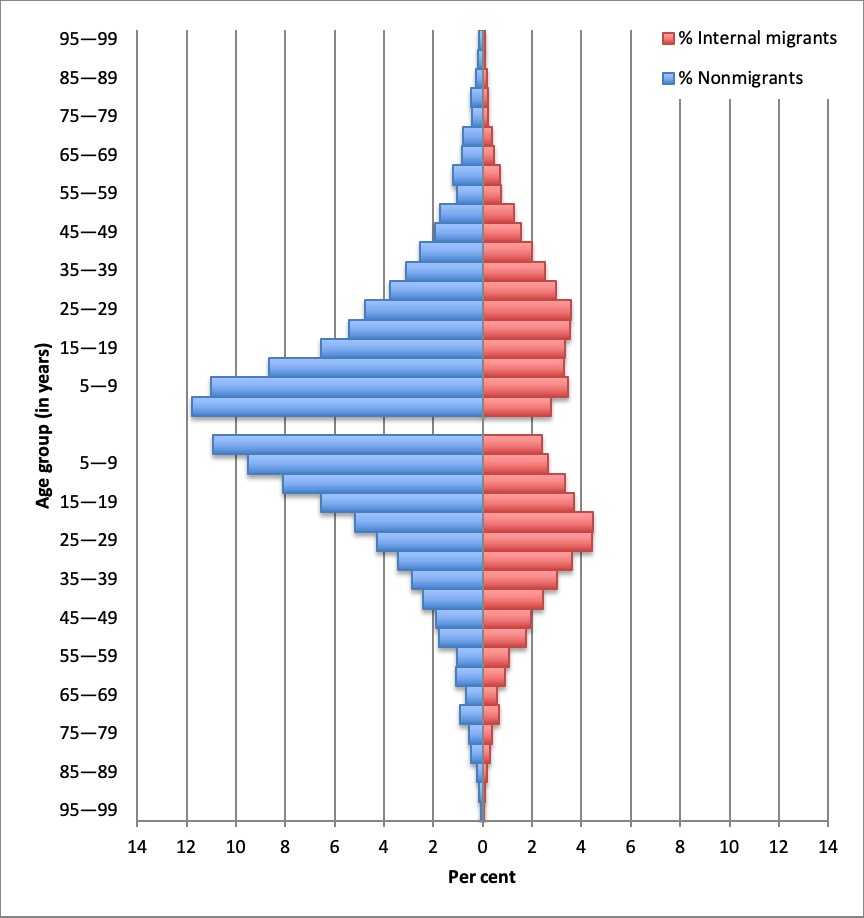

Newer research into gender and migration in Ghana and elsewhere go beyond such labels to explore trends and patterns behind increasing female mobility. In Ghana, our analyses of disaggregated data from the 2000 and 2010 Censuses reveal that working-age migration peaks earlier for females than males and is a key feature of migration for both sexes. As detailed in our paper “Contemporary female migration in Ghana: Analyses of the 2000 and 2010 Censuses,” female internal migrants experienced a number of demographic shifts between 2000 and 2010. The 2010 Census recorded the first time in which the percentage of female migrants overtook female non-migrants. More women aged 25 to 49 years were migrants than non-migrants (Figure 1, bottom).

By 2010, unmarried women in Ghana were likelier to migrate than married women. Female migrants were likelier than female non-migrants to reside in urban areas and to report working for pay, profit, or family gain. Given the prominence of rural–urban migration and the economic opportunities that exist in urban centres, economic opportunity appears to be an important driver of female internal migration.

Economic motivations amongst migrant kayayei

Female migrants working as head porters (kayayei) in Ghana’s urban centres (Figure 2) epitomize the current trends in contemporary female migration in Ghana. To complement the limited depth of information on female migration available in census data, we conducted a mixed-methods study amongst female migrant kayayei to examine links between migration and health. We surveyed 625 migrant kayayei in Accra, Ghana using respondent-driven sampling. Forty-eight survey respondents who reported a recent illness or injury were selected for in-depth interviews to further probe links between migration and health. This physically demanding work requires agility, endurance, and strength. The average kayayei carries 88.3% of her bodyweight on her head over 1.5 km in distance; kayayei carrying both babies and loads carry an average of 114.8% of their bodyweight.

Almost all participants (97.6%) cited employment as a primary reason for migrating to Accra, with 93% of participants intending in advance of their migration to obtain work as kayayei. Interestingly, employment opportunities drive a higher percentage of migrant kayayei than the general internal migrant population residing in Accra’s informal settlements. In a study of 239 internal migrants in two of Accra’s informal settlements (Nima and Old Fadama), 68.2% of respondents reported migrating to Accra for employment, followed by 8.8% for education, and 8.4% for family-related reasons (e.g., accompany spouse or parent). Migrant kayayei come to work and earn money to support themselves or their families. Many earn more than Ghana’s minimum daily wage and send home significant remittances more frequently than male migrants.

In our in-depth interviews, participants frequently discussed how they assumed the role of provider in response to family events (e.g., death, separation/divorce, illness, inability of polygamous husband to support multiple wives and children), debts (e.g., inability to pay for emergency medical expenses, loan repayment), and a need to diversify household income following poor farming harvests. In these situations, migrating to Accra for work as kayayei enabled participants to remit their earnings and provide crucial financial support to their families at difficult times. Remittances also enabled participants to cover school fees and school-related expenses for their younger siblings and children. Thus, investing in the education of siblings and children served as a sort of insurance to secure kayayei’s own futures:

I cannot go back to school because my family are no more there. We’re left with only me and my junior sisters, two. They are going to school. If I go back to school, who will take care of all of us? […] I left Bolga [Bolgatanga] and I came here [to Accra] because in Bolga, there is no work for me to get money to support my junior sisters to go to school. I want to help my junior sisters because I did not get anybody to help me go to school. And I am the senior. So I decided to work and help them so that maybe one day, one day when I grow, they will also take care of me or they will take care of my children.

– Frafra woman aged 21 years, who remitted GHȻ 107 (US$ 19.78) monthly

In addition to providing immediate financial support via remittances, many participants reported long-term savings goals. Entrepreneurial motivations drove participants to migrate for work as kayayei so that they could accumulate income to invest in starting their own businesses back home.

Addressing the impacts of increasing internal migration

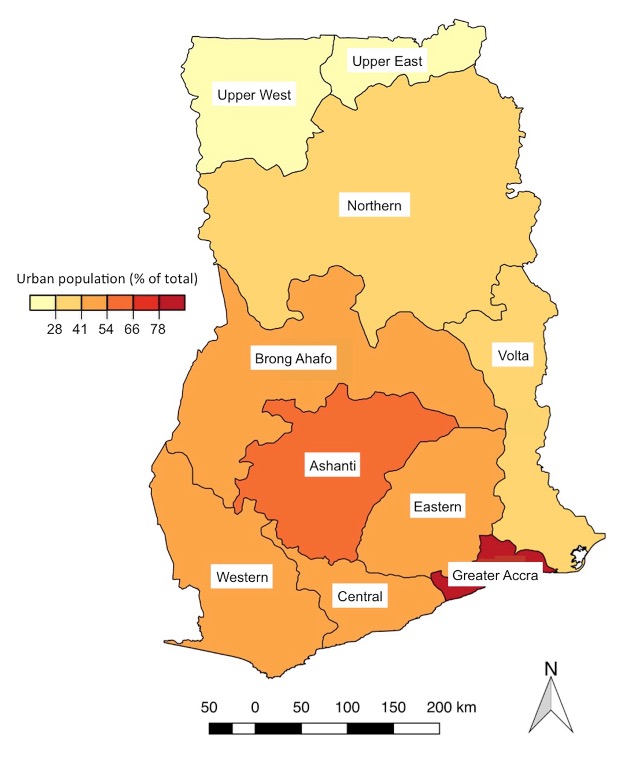

To more effectively address the impacts of growing internal migration, such as urbanization and productive labour losses, census analyses should include greater attention to examining patterns, trends, and differences in the migration patterns of women and men. Our analyses of Ghana’s most recent censuses show that female migrants in Ghana are increasingly mobile, independent, and driven by economic opportunity. The Greater Accra and Ashanti Regions, Ghana’s only regions experiencing positive net overall migration, are particularly attractive destinations for female migrants seeking employment.

This growing urbanization, however, has resulted in the scapegoating of migrant kayayei. Migrant kayayei come to Kumasi and Accra in such great—yet unknown—numbers that the media and politicians have labelled them an “urbanisation crisis” or “menace”. Government offices and nongovernmental organizations in Accra have attempted to address this issue by providing training programmes for kayayei, registering a select few for health insurance, or improving housing conditions for kayayei in Accra. While these efforts may have improved kayayei’s quality of life in Accra, they have not reduced the flow of rural-urban migrants.

Simultaneously, productive female labour losses in eight of Ghana’s ten regions may negatively impact local development efforts and local economies. If policymakers are serious about addressing net out-migration in Ghana’s more rural regions and managing urbanization, then they must actively seek out the migrant kayayei and listen to the reasons driving girls and women to migrate. If a common driver of migration amongst kayayei is to acquire the necessary funds to start a small business venture, for instance, then increasing women’s access to microfinance could help reduce net out-migration.

Many interview participants spoke about missing their children and families, and they would certainly appreciate an opportunity to earn sufficient income and/or start their own businesses without having to leave their families behind. In Ghana’s more rural regions, interventions focused on poverty reduction, increased access to financing for female entrepreneurs, and the development of more economic opportunities specifically for girls and women could help minimize factors currently contributing to net out-migration in rural Ghana.

Samantha Lattof is a Visiting Fellow in the Department of International Development at the LSE and a global health consultant.

Ernestina Coast is Professor of Health and International Development at the LSE.

Tiziana Leone is Associate Professor in Health and International Development at the LSE.

Philomena Nyarko is a Consultant at the University of Ghana, Legon and former Government Statistician for Ghana Statistical Service.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.