On Friday 29 January Akosua Adomako Ampofo gave an online lecture, “(Still) Decolonizing Academia? Pain, Trauma, Imagining, Healing & Recovery” as part of the Cutting Edge Issues in Development Lecture series. Akosua Adomako Ampofo is a professor of African and Gender Studies at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ghana (UG) and the President of the African Studies Association of Africa. Read what Health and International Development MSc student Roberta Kisubi took away from the lecture below.

You can watch the guest lecture back on YouTube.

In describing the concept of decolonizing, Professor Ampofo stated that “it is the beginning of a process, a prognosis of options to experience liberty, healing and restoration of the colonised.” From her description, decolonizing involves using one’s imagination to define what a post-colony embodies and then harnessing one’s resources whilst leaning on community to make this imagination a reality. Her description of decolonizing is powerful and reaffirming because it reminds us that whilst the process of decolonizing is a battle, in this generation, we have the option of choosing what weapons we can use to realise epistemic freedom. Epistemic freedom can be understood as an imagination and realization of self that is not rooted in colonial oppressive narratives. This is echoed in the musical masterpiece, Redemption Song, by Bob Marley where he sings ‘emancipate yourself from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds.’

Following her description of decolonizing, Professor Ampofo’s overall message emphasized the need to remain steadfast in the challenging fight against systemic racism in academia and daily life. At the start of her talk, she paid tribute to some of the greatest black people in history. Seeing images of the late Kobe and Gianna Bryant, John Lewis and Bill Withers was extremely emotional and powerful because their success is an embodiment of how using one’s talents can be a key tool in the fight against colonial oppression. This definitely served as a stark reminder about the value that lies in imagining what freedom can look like and persevering to achieve it. As Kobe Bryant appropriately put it “everything negative – pressure, challenges – is all an opportunity for me to rise.”

She comically highlighted that some people have continuously referred to her as a ‘decolonizing aunty’ because she continues to engage in a topic that is sometimes framed as ‘all talk and no action.’ In response to that however, she says that certain events lead to a ‘remix’ of how decolonizing is understood through evoking a new energy to the struggle and reminding us that ultimately the process is an act of necessary resistance and therefore, we must continue in the pursuit of our imagined freedom even when it feels futile. She drew on the killing of George Floyd, the Black Lives Matter protests as well as the Fees Must Fall and Rhodes Must Fall student protests in South Africa as a renewed commitment to resisting colonial oppression. To further emphasise the point of persevering in the struggle against decolonizing, she very cleverly stated that just because chronic illnesses like diabetes have been given attention, it doesn’t mean that we stop doing the necessary research to understand how to treat them better. Relating this back to decolonizing, in a space like LSE, this could present itself as a critical reflection of the diversity in the reading lists. Perhaps a challenge to the students reading this is to review the extent to which key academic course texts in economics, colonialism and development include the perspectives of non-white scholars.

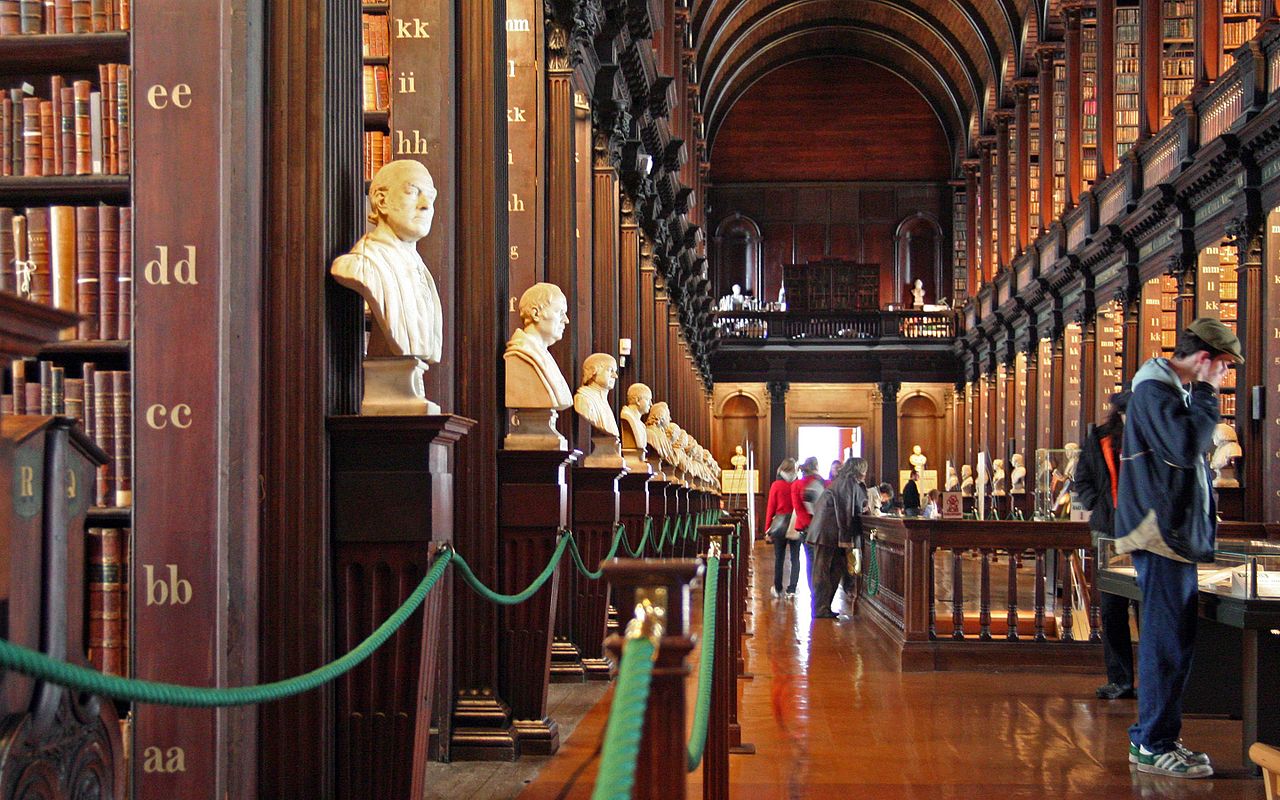

A particularly touching aspect of her lecture was when she invited the audience to share their experiences of racism and colonial oppression. Experiences shared included heart-breaking accounts of colourism and intentional mispronunciations of three syllable African names. This moment was poignant but also a necessary reminder that epistemic violence and racism isn’t solely situated in the libraries of academic institutions but also in the day-to-day lives of black people. She drew on global examples as well such as the Ugandan climate activist, Namugerwa Leah being referred to as the Greta Thunberg of her country which echoes the words of Ngugi wa Thiong’o that epistemic violence is the removal and replacement of black people’s mindsets with that of white people.

In speaking about decolonising academia, she importantly pointed out that white academics and politicians need to actively take on the role of educating themselves without placing this burden on black people, especially because technology and social media provide the ability to access accurate educational information instantly. When it comes to social media, however, it is important to remember that posting a hashtag against racism must be followed with clear anti-colonial efforts. An interesting conversation followed between Professor Ampofo and the discussant Rishita Nandagiri around including more non-white voices in academia. The voices of scholars such as Amartya Sen have heavily dominated academic writing as the non-white voice. Whilst his contribution to economic thought is invaluable, the academy needs to make active efforts to include more non-white voices. Perhaps several institutions can pick a leaf from the University of Ghana that provides a compulsory ‘African Studies’ course to all its undergraduate students with the aim of making space for decolonized knowledge. Similar efforts have been made at Rhodes University (University currently known as Rhodes) where a doctorate was awarded to Madosini Mpahleni, a traditional musician and healer. Of course, one might question the extent to which this is truly a decolonial effort if Dr. Madosini’s work can only be viewed as legitimate if it is recognised in the parameters of colonial education awards. Nevertheless, in reflecting back on my primary school days in Uganda where we were taught that John Speke discovered River Nile, the presentation of a PhD to Dr. Madosini reminds me that decolonising academia must focus on an active inclusion of African knowledge in curriculums. It is not adequate to have more black scholars in the curriculum if they are teaching colonial curriculums. Professor Ampofo recognised that a lot of traditional African knowledge has been lost as it was traditionally expressed orally but that we can revive it through the use of song, photography and re-connecting with the ancestors.

From a policy standpoint, government leaders globally need to critically reflect on the ways in which the history of colonialism continues to manifest and marginalise black communities in education and healthcare and the implications of this for economic growth. A clear example of this highlighted by Professor Ampofo is the scepticism of black people on taking the COVID-19 vaccine which is rooted in black people being used for medical experiments by colonialists e.g. The Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

As I concluded this blog post, I was uncomfortably reminded that all the non-white names in this piece had the red ‘spelling error’ line underneath them. Perhaps the next step for me is to contact whoever is in charge of spell check at Microsoft to begin a conversation to address this. In the rap hit single ‘I can’, Nas reminds us that before we faced colonial oppression, “we were kings and queens, never porch monkeys.” These lyrics affirm our intrinsic value and remind us that we are not puppets engineered to satisfy the white gaze on the colonial stage. We must continuously recognise that we hold value and work towards achieving our imagined reality of epistemic freedom. In the words of Professor Ampofo ‘if we cannot imagine a post colony, we cannot create it.’

This next lecture in the Cutting Edge Issues series will take place from 4-6pm (GMT) this Friday 5 February. Yuen Yuen Ang will be joining us from Michigan to give a lecture on ‘Unbundling Corruption: Why it Matters and How to Do It”. LSE staff and students can sign up for the lecture here and external audiences can join the lecture via YouTube.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.