On Friday 5 February Yuen Yuen Ang gave an online lecture, ‘Unbundling Corruption: Why it Matters and How to Do It’ as part of the Cutting Edge Issues in Development Lecture series. Yuen Yuen Ang is a professor of political science and China scholar at the University of Michigan. Her second book, China’s Gilded Age: the Paradox of Economic Boom & Vast Corruption was published in 2020. Read what ID MSc Health and International Development student Nick Williamson took away from the lecture below.

You can watch the guest lecture back on YouTube.

When I think of corruption, my mind wanders back through history to the gangs of Victorian London. I imagine gangsters in flat-caps, greasing the palms of local bobbies. Yuen Yuen Ang, in her insightful and absorbing lecture, made me think again. Corruption remains a sizeable cog, turning behind the scenes of business and politics today.

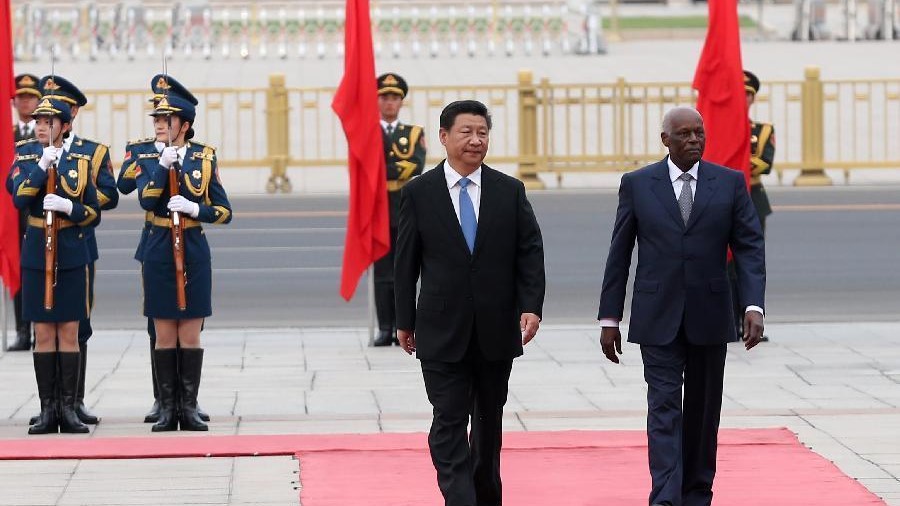

Bringing to light both the similarities and differences between the United States’ Gilded Age and today’s development trends in China, Ang’s lecture shared with us a small but fascinating insight into her theories on corruption, presented together in her new book: China’s Gilded Age (2020).

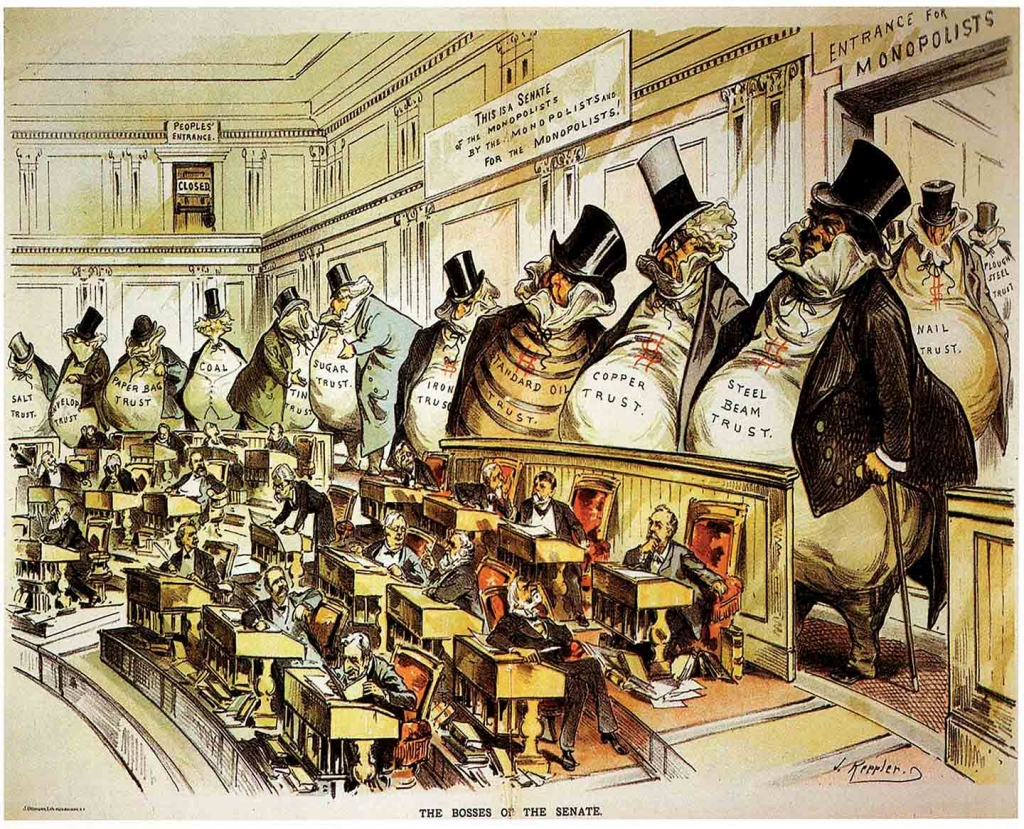

During the Gilded Age in the United States (c. 1870-1900), the nation grew as immigrants arrived looking for work in a nation mutating with industrialisation. The Wild West was being “tamed”. Elites were getting richer while the poor became poorer. Corruption was in the fibres of this Gilded age. Enterprises paid politicians, instead of policemen, for the freedom to extract the wealth of a young nation. Corruption even influenced the New York legislature in the late 19th century, a testament to its omnipresence. Politicians were in the pocket of extractive corporations.

My first takeaway from Ang’s lecture was that corruption may not always be bad for growth. This idea contrasts with widespread beliefs about corruption and its maleffects, just one of the stimulants prompting a lively discussion at the end of the lecture between Ang and the economist Mushtaq Khan. But Ang is not suggesting that corruption is good. The issue she raises for consideration, rather, is what types of corruption are taking place around the world, and what their long-term consequences will be.

Ang shows that although corruption is widespread across the nation, China continues to grow and evolve. This, she argues, can be explained by the type of corruption taking place. Breaking it down, Ang selects four vignettes of corruption for her analysis. Two of these are petty theft and grand theft, both of which are deemed unambiguously harmful to growth. The latter two, however, involve exchanges. Ang describes what she calls speed money, likening this to petty bribes to quicken project approval or gain a necessary licence. Second, there is access money, bribery on the elite stage for lucrative business deals. These are what Ang describes as the steroids of capitalism. Ang explains these concepts here.

Steroids is a metaphor clearly chosen with care. Access money can enable enterprises to gain tax breaks or land-access for large-scale projects, which arguably leads to economic expansion. Like steroids, however, these economic injections pose serious risks.

Ang concluded her talk by presenting her findings from a pilot study into the structures of corruption between countries, proposing a new comparative tool: The Unbundled Corruption Index. Ang is looking to find out what the effects of corruption are on the economy, beyond just looking at GDP. The answers lie in her book.

This is not Ang’s first time speaking at the LSE, and for good reason. With an extensive knowledge of the relationship between corruption, extractive institutions, and political governance, Ang gave an accessible and colourful talk. By likening variants of corruption to toxic drugs, painkillers and even steroids, complex issues were broken down into understandable and entertaining metaphor.

Ang has compelled me to explore more about corruption in a global context. I am left wondering about how corruption in all its forms may impact other aspects of development beyond economics alone. Could it be the top-down structure of China’s economy that encourages corruption? Ang reminds us that even in the U.K., corruption persists and must be questioned. Although the flat-caps are gone, today there is cronyism of a different kind. Of the over £16 billion in UK government contracts made public as of December 2020, almost half of this colossal sum went to companies that were linked, connected, or associated with the Conservative Party.

Holding global leaders accountable for acts of cronyism, favouritism and corruption, especially in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic shake-up, will be critical as we recover and reset in 2021 and beyond. Ang’s development of the unbundled corruption index will help expose this serious, yet all-too-common problem, under a different light.

The next lecture in the Cutting Edge Issues series will take place from 4-6pm (GMT) this Friday 12 February. Kate Raworth will be joining us from Oxford to give a lecture on ‘Doughnut Economics: turning a radical idea into irresistible practice’. LSE staff and students can sign up for the lecture here and external audiences can join the lecture via YouTube.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.