In this article, Boluwatife Ajibola lends support to what he calls techmanitarianism – the prioritisation of ethical standards and humane concerns in big data-gathering undertakings. Insights are drawn from his review of a paper by Linnet Taylor and Dennis Broeders – In the name of Development: Power, profit and the datafication of the global South.

Majestic as his name sounds did Royalty walk into the cozy community auditorium with his friend, Smith, where about four dozen young community volunteers were seated on white linened plastics adorned with wine tapings on the chaise. It was a book launch. As they prepared to welcome the Author, a proprietor at the village’s central college, was an attendance sheet passed round. “Please, let’s have your name, contact details and other essentials”, the compere announced. Royalty buzzed his friend, “Pass to the next, what for?”. Smith muttered, “Your name at least, brov”. Royalty, fixated on the screen of his cell phone yelled, “No! I’m cool”. Few seconds after was Royalty greeted on his phone by an Ad, ‘The next intervention visits your community, register your details’, the Ad reads. It was a busy atmosphere, time was a luxury to check for further details, Royalty had just engaged the keyboard and had clicked ‘submit’.

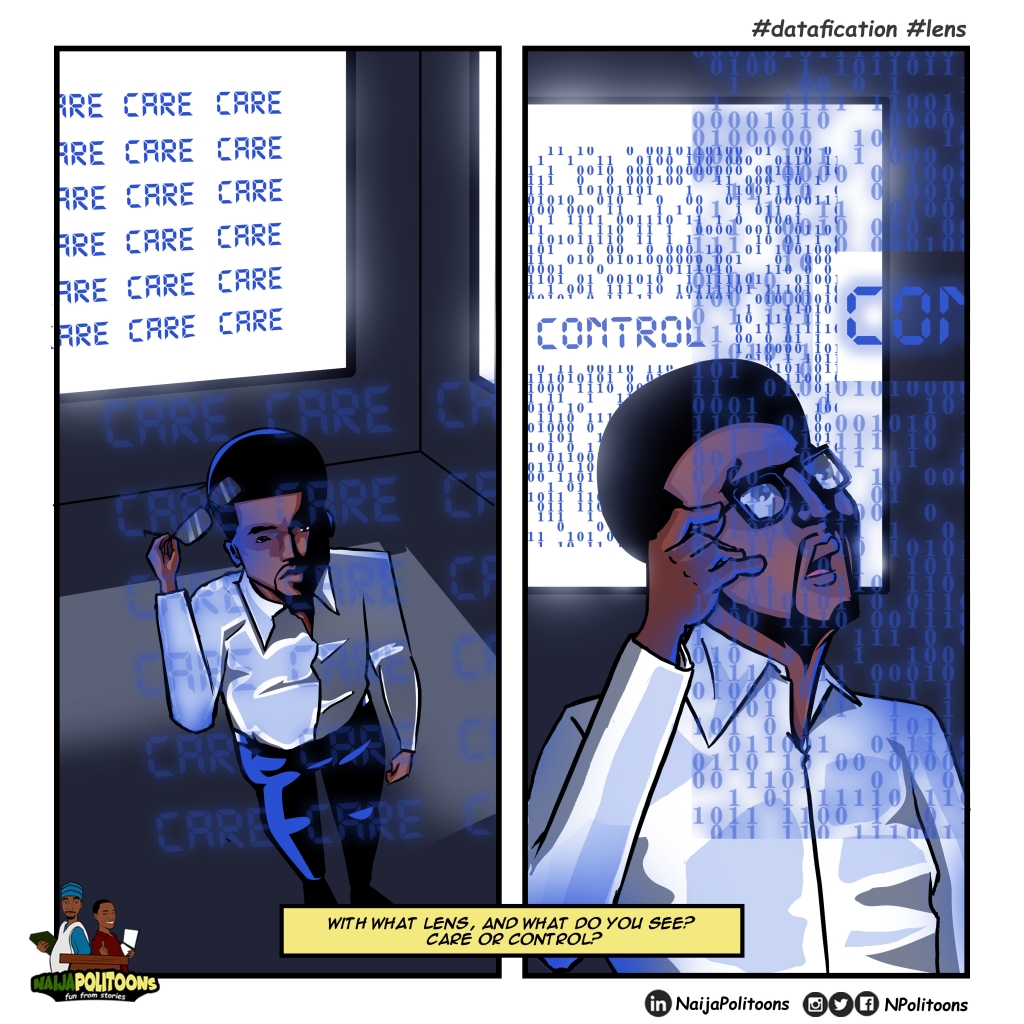

This scenario, in part, mirrors notions about the regime of big data as a currency with which vulnerable people pay for development services. They, being oblivious to subterranean intentions and models, trust corporate institutions with a range of information that would be ordinarily withheld from ‘strangers’ with unveiled faces. While some development interventions are wrapped in motives of care and compassion, some are, in extant times, found to be by-products of larger-scale processes of informational capitalism. In the name of development, what do we see? Power contest or care, profit or values, datafication for development planning or dataism for behavior control. Taylor and Broeders, in their article, investigate this process of datafication in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs), where new ICTs through the uptake of mobile phones and the internet, generate big data. This raw material underscores a perceived switch and shift. A shift in power structures within the field of development to private sector corporations and a switch in-terms of primary access to consumer data, whereby corporations access data first before governments under which such data are collected. The paper contributes to a scarce debate on political (power) implications of datafication, from the developing world.

Why would Royalty (un)consciously prefer to respond to an Ad and not the sheet? Perhaps the former was poised to deliver some gains to him, and his community (although unaware of the uses of the information provided), rather than a straining demand posed by a piece of paper that he can simply “pass to the next”. This reflects perceptions about development planning whereby the multiple coinciding of ICT4D, the SDGs, technological innovations and a quest for big data are underlined by models that sources of these data are not aware about, following their exclusion from post data-generation processes.

The commercial emprise of datafication wrapped by abstracted representations of people in LMICs through the data they provide are, moreover, projected as intervention-targeting and monitoring, or as put by Taylor and Broeders, data doubles. Informational capitalism itself raises concern about privacy, and it signals the shift from care (wrapped as development motives) to control. Only a shred of evidence would testify much more about a power shift from traditional modes of data collection by states to informational or surveillance capitalists than this, where the accumulation of power in development planning is not only data-construed but also unwittingly volunteered.

Taylor and Broeders acknowledges this to be a shift from legibility to visibility. Traditionally, data collected at population level are legible and provides grounds for governability and accountability, as opposed to visible data gathered by third parties who do not only find these data easy to use but also viable for the expansion of (political) power in driving development agendas. A hunch here is the perception of the world as a laboratory wherein social and data scientists experimentally engage the human behavior, in which the former studies the behavior and the latter accumulates power to control same behavior.

Beyond the individual are risks against state sovereignty as a result of visible data’s capabilities to expose sacred economic and social dynamics, reinforced by diminishing levels of accountability, which further leads to the strengthening of information capitalists as regnant actors in the field of international development. Although, the decentralisation of power underlines development planning, however, an excessive reliance on multinational technology corporations emplaces data as capital and redefines development as market expansion. The regime of data capturing from multiple sources, by all means possible, thence, precures the movement of web models across informational, interactional and transactional stages.

Extending the frontier of knowledge shared by Taylor and Broeders would also be the possibility of new innovation models within LMICs and by the poor communities, as referred by Heeks – per poor, although it is argued that the developing nations have high software piracy rates. Nonetheless, this side of the divide can set the pace for a new techmanitarian agenda, if actions by the giants are not popularly delectable. Also, the call to bridge technology gaps in the developing world is today heralded by an increasing level of technological innovations originating from these regions – a feature of the ICT4D 2.0 and its successors. On the other hand, pragmatically, extant realities suggest the potentiality of informational exploitation of the people by the people, further illustrated by the disparate level of access enjoyed by the LMIC populations to these technologies and the connected levels of inequality. Another is the power shift from states to their citizens, or what I call the ‘re-framing of the poor’. As there is an increasing uptake of these tools and technologies to hold governments to account, demand for good governance, and social and development policies. Nonetheless, the tech giants from the west possess a high latitude to control these on-ground activities from their central ‘cursors’, shaped by their (un)veiled models.

The accumulation of power through a combination of processes that however excludes data sources from post-data generation efforts, reinforces the vulnerability of sources. What does this indicate about the future of development planning? While a divorce of technology corporations from development agendas is not in view, the prioritization of ethical standards and humane concerns should marry big data-gathering aims. Hence, TECHMANITARIANISM. As the world seeks to address development challenges in LMICs, it should not unconsciously lay foundations for a vicious cycle of vulnerability – with a potential to welcome a post SDG United Nations plan that will be framed largely around the tech business and its frailties.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

What a loaded write up

Educative.