On Friday 22 October, Clare Short gave an online lecture on ‘What’s wrong with Aid?’ as part of the Cutting Edge Issues in Development Lecture Series for 2021/22. Clare Short was Secretary of State for International Development 1997 – 2003 and responsible for the establishment of the Department for International Development. ID’s Professor James Putzel was an invited discussant for the lecture. Read what MSc students Emily Piper, Sofia Fiolhais, Abdelbari Lahkim Bennani and Diana Liedloff took away from the lecture below.

You can watch the lecture back on YouTube or listen to the podcast.

At a time where it seems the world is facing greater divisions, where nationalism is spreading across the world, where there is disappointment and negativity, Clare Short provides a glimmer of hope and an optimistic view for the future of development.

Clare Short has been described by many, including Andrew Mitchell (a British MP who served in the Cabinet as Secretary of State for International Development from 2010 to 2012) as a brilliant development secretary. In 1997, Short oversaw the transformation of the previous ‘Overseas Development Agency’ into the newly independent Department for International Development (DFID). She has continuously fought to put development at the forefront of government agendas and as a consequence has contributed to the success of development efforts over the past few decades. Personally, I am particularly grateful for her contributions to development as I grew up with a parent who worked for DFID, therefore have seen how important development has been to the lives of many individuals.

In her most recent lecture on ‘What’s wrong with Aid?’, Short started by outlining her argument – development discourse needs to be repositioned to meet the challenges of the current era. She explained that swings in attitudes towards development reflect the values of political eras. Currently, Short argued, the UK and global attitudes are moving towards a hostile attitude to aid which is less committed to development. She briefly outlined past political eras and their influence on development, touching upon four key moments:

- Post-war, when 60+ countries became independent. The UN was created and there was an enthusiasm for development

- The Pearson Commission report argued that whilst the need for aid will not disappear over a few years, it is not a permanent feature of relations between the rich and poor countries, therefore seeing an end to the need for development.

- The debt crisis in the 1980s created a global recession, where the focus was on markets.

- The end of the cold war cut defence spending. Short arguesd that there was confusion amongst international leadership about priorities. She even mentioned conversations she had with ‘C’ in MI6 (referred to as M in James Bond) over whether they should spy on developing countries. To Clare Short, this was not a priority as she was hoping to create partnerships with these countries.

After this very brief history lesson, Short suggested that we are now in an era where division and nationalism are spreading across the world. Now is the time to reposition the discourse in aid and development.

She notes that recently there has been a call from various sources (which are not development focused) for international collaboration to deal with crises such as climate change. For example, the Financial Times is calling for a new agenda, to protect the weak, promote resilience etc. because international systems cannot cope unless the needs of developing countries are taken seriously. People need to recognise that if we want to look after ourselves, we have got to take on a global agenda and be interested in poorer people in developing countries.

There is a recognition for unity and global collaboration, therefore focus in the development discourse should move to the need for international cooperation to prevent the potential damage of global crises such as climate change and environmental collapse.

Short even draws upon something Boris Johnson, who demolished the Department for International Development, said at the United Nations Climate Change Conference 2021. Boris acknowledged it is “time for humanity to grow up. If we don’t our planet will become uninhabitable for humans and other species”. Johnson pointed out that the UK started the Industrial Revolution, and should take responsibility for the developing world seriously.

We cannot afford to be selfish.

So where does this leave us going forward? I managed to ask Short about the future attitudes towards development and whether we will see the return of DFID.

She responded by stating that we are in an era of disappointment, negativity and nationalism. Students and researchers have an important role to play. We need new analysis, research and thinking on ending conflict. Military and development engagement does not work, we need to learn how to work better in fragile states.

She added that the re-establishment of DFID is unlikely to happen anytime soon. But this should not stop us from staying alive, finding arguments, being critical of budget cuts and of what the Foreign Office is up to.

Development discourse needs to grab hold of the opportunity to challenge the current discourse which is on crisis and tragedy to show how solutions can be found and progress can be made.

She ended by challenging future actors in development to change the message to one that values international solidarity. As this is the only way to rescue our planet and our international economy, with peace and security from damage that will endanger the future for everyone.

A message that I think is not only central to development but central to humanity – look after one another.

Emily Piper

_______________

Clare Short, the former Secretary of State for International Development from 1997 to 2003, makes a strong argument on the need to shift the developing and aid narratives towards international cooperation, and away from the emotional image of the poor.

Ms Short began her lecture by briefly outlining the historical changes of these narratives. In the 1960s, the independence of several colonies launched the new era of aid and created this idea that like the Western Countries – who were able to industrialise and develop – so would now the newly independent countries. And while some progress was made throughout the 70s, the Debt Crisis in the 1980s represented a disastrous era for Latin America and Africa, with decreasing GDP and rising external debts. Washington in 1989, established neo-liberalism as the guiding principle for aid and from the end of the Cold War on, aid programs have been improved. With the turn of the century, came the Millennium Development Goals with the reduction of poverty at the centre. More recently and with the Sustainable Development Goals, a new concern for international cooperation has been emerging, under the threat of climate change and now, the pandemic.

Climate change, as stressed by the speaker, came to emphasize the need for multilateralism, in an era of emerging nationalism. Indeed, there is a common understanding – both in the public and private sector – that this crisis cannot be solved on a national level. In fact, 70% of all investment needed to confront this challenge, must be on developing countries, meaning they have to be part of the global agenda. Ms Short eloquently underlined the importance of taking advantage of that in the discourse around aid.

Ms Short concludes by emphasizing that the face of aid and international development, must move away from using the poor and their fragility to attract funds. The new image of development has to be international solidarity and the rescue of our planet and international economy.

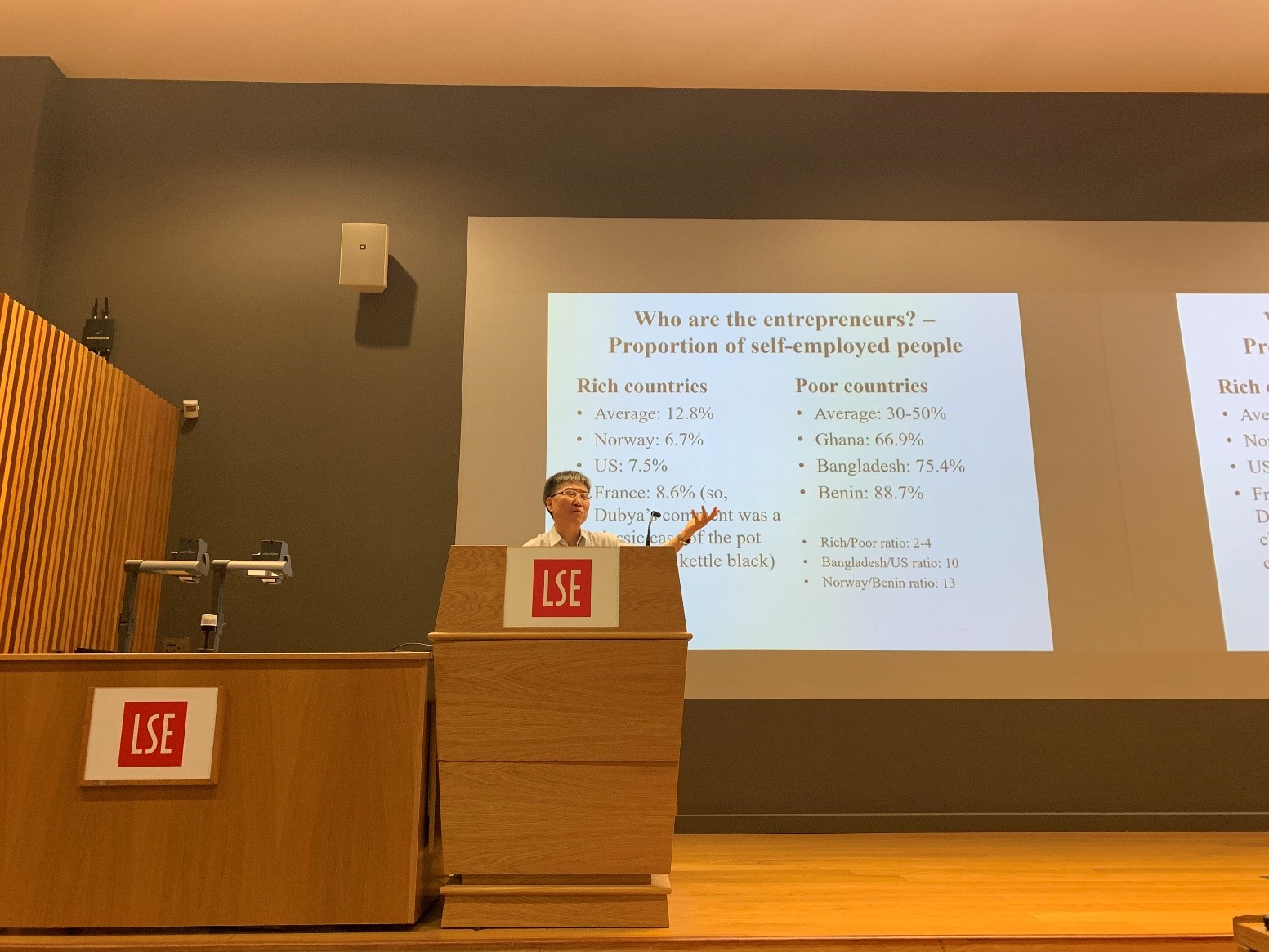

The second speaker was James Putzel, Professor of Development Studies at LSE. Agreeing with Ms Short on how developing countries have to be at the centre of the global agenda for crisis resolution. Professor Putzel makes a strong argument on the self-interested sphere of aid: aid is mostly attractive to developed countries once they do need the developing countries in order to face the threats of the new millennium.

In addition, Professor Putzel points out the central role given to markets and business actors on development, as the private sector constitutes a pillar of neo-liberalism. However, it is outlined the necessity for public sector guidance, by regulating and orienting the action of the private sector.

Personally, my key takeaways from the lecture were the need for further thinking and research on the discourse that should surround aid and development, together with the role the private sector and the profit-maximising values should play on international cooperation and aid. We are facing global threats, which demand global cooperation, yet the rules of the game are still being defined.

Sofia Fiolhais

_______________

The lecture that occurred on 22nd October 2021 addressed the interrelationships between aid and development with guest speaker Clare Short (former Secretary of State for International Development) and James Putzel (Professor of Development Studies).

Clare Short talked about the current global hostility towards aid and the general cuts driven by ideology. She then talked about the evolution of aid historically where it began after World War II, with the initial philosophy of helping the developing countries catch up to the industrialized world. Therefore, the UN members intensified efforts to initiate and sustain economic growth in 1961. This global movement faced a halt because of the political attitude in the 1980s, where both the global recession and Washington Consensus occurred, and the rise of neo-liberalism led to catastrophic results for both Africa and Latin America. This was followed by the end of the cold war, with cuts in military spending and international confusion that arose about the role of the state’s leadership.

World leaders started focusing on Millenium Development Goals as tools to frame efforts on international development, this gave way to progress but still, more effort is required. This effort is also being challenged by a tide of nationalism and cuts in aid as well as the existential crisis of climate change. She then argued this could be an excellent opportunity to engage international commitments on developing further the sustainable development goals and the zero-carbon emission by 2050. With a current tide of increased military spending and cuts in aid, international collaboration is possible if all parties and states are included in the discussion. Including developing countries is important because there is a global demand for energies from the Global South alongside global issues that affect all parties (including migrations crises and geo-political threats), hence incorporating the Global South is paramount.

Clare Short also argued that resolving the root cause of the development issue should be on focusing efforts on building strong sustainable institutions in fragile states rather than just giving aid and quantifying the number of beneficiaries receiving the service. This should also be done by changing the media message from helping people to collaborating in an effort of international solidarity.

James Putzel then discussed how aid is instrumentalised by big companies and is linked with the military, aid is then used to promote western commercial interests. However, he did note that there was progress when it came to accountability as donors had to prove aid was not for commercial or military purposes. He then explains the original conceptualisation of aid as historical; the real barrier was in the middle-income countries stepping up to reach the club of wealthy countries. However, James Putzel also stated the issue was a structural one and that the main challenge was the neo-liberal policies that allocated the central role of the future of development to the market and private sector rather than governments. He believes it can only be done with a strong public sector that is involved to regulate the body. He then concludes that it is more important than ever for the resources to be channelled to states that suffered from structural disadvantages, and that these resources should be used to address global issues, such as fighting the pandemic. Finally, he agrees with Clare Short that one cannot address climate change and health without incorporating the developing world.

Abdelbari Lahkim Bennani

_______________

Reflecting on the swings in attitudes in international development, Clare Short, former Secretary of State for International Development from 1997 to 2003, discussed ideas around the blemishes of development aid, emphasising the necessity to learn from past mishaps and to shift the conversation around development.

She argues that the current cuts in development are induced ideologically by pure hostility to aid and development, which is reflected in the British right-wing press. However, looking back ten years earlier, the change in attitudes towards foreign aid is stark. The Conservative Coalition government under David Cameron, elected in 2010 after a long period of Labour control, showed interest in progressive development discourse and increased support for foreign aid and development to match Labour’s commitment to international development, to promote its reputation and demonstrate its soft power abroad. Rightly so, Short claims that these swings reflect the values and attitudes of different political eras.

Short then proceeds to reflect on the history of international development, from the end of the Second World War with its eagerness towards development up until today’s era of great divisions such as populism and nationalism, to analyse the fluctuating mindsets throughout history. By scanning through the latest newspapers and reports, Short brings to our attention that even organisations that seldom participate in development discourse call out for international collaboration in order to tackle climate change. Arguably, the highlight of this short review is the quotation of Boris Johnson, who has recently implemented foreign aid cuts and abolished the Department for International Development, stating that nations “have to grow up” or else we are going to be faced with the problems of desertification, droughts, crop failure and mass ecological immigration. In his quote, Johnson raises attention to the intergenerational equity issue—e.g. the use of one unit of non-renewable energy today cannot be used by future generations tomorrow—in which the British Industrial Revolution played a major role. Short believes that Johnson’s newfound rhetorical commitment to taking responsibility for the developing countries shows that there is some leeway for development discourse to change.

There are numerous issues related to aid such as the negative impact of tied aid on the recipient countries or the issue of overstaffed organisations which use up precious time and money that could be better invested into empowering the very people whom the mainstream Western media often blames for the tragedy of the commons. Short urges us to learn how to navigate fragile states and to reconsider the military-first approach that is often implemented to no avail. Instead, the locus ought to be on empowering countries to create their sustainable institutions on their terms, and thus moving away from aid measured merely through short-term metrics. The global image of charity is problematic and patronizing, however, she argues that global cooperation and good entrepreneurship are key to tackling climate issues. She ends her argument on a positive note, stating that the understanding of ecological degradation creates a major opportunity for the formation of collaborative solutions to international problems while maintaining international peace and security.

In my opinion, Clare Short’s arguments are highly relevant and useful in terms of what past development programmes could have done better, and how future development thinking should change. However, I believe the linkage of global peace and security to climate change, being the sole independent variable, can be rather dangerous. We must remind ourselves of the underlying asymmetric power relations that often characterise aid, especially in combating climate change. I believe this is exactly what Short is hinting at as developing countries require self-made, strong and democratic institutions which can take care both of human and non-human inhabitants while collaborating with other countries to do the same. In order to achieve this, international solidarity must resurface again to heal our fractured world.

Diana Liedloff

_______________

The next guest lecture will be with Mushtaq Khan on Friday 29 October 2021 on ‘Making Anti-Corruption Effective: A New Approach’. LSE Students, Staff and Alumni can register here. External audiences can join the lecture via YouTube.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.