PhD student in LSE Department of Government Meshal Abdulaziz Alkhowaiter examines how equalizing labour market mobility can reduce the wage gap between domestic and migrant labour, focusing on Bahrain as a case study.

Earlier this month, I wrote about the importance of implementing a universal minimum wage for all private sector workers in Saudi Arabia regardless of their nationality as a policy tool to bridge the cost gap between nationals and foreign labour. In this article, I will argue that equalizing labour market mobility for all workers will indirectly reduce the large wage gap between citizens and expat labour. I will further argue that such labour reforms will make citizens more ‘employable’ in the private sector, as workers will compete based on merit rather than their cost and the different labour protections granted to each group. Specifically, I will be using empirical evidence from Bahrain, which introduced several labour market reforms in 2008 and 2009, respectively.1 While all Arab countries share the same job market peculiarity where citizens have greater labour protections compared to foreign employees, I will particularly focus here on Saudi Arabia because it has both the largest labour force in the region and the highest unemployment rate amongst citizens. Lastly, I will discuss Bahrain’s effective experiment with labour reforms and argue that results can generalize to Saudi Arabia’s labour market as well.

To combat unemployment amongst nationals and make its labour market more attractive for skilled foreign employees, Saudi Arabia passed several policies in March 2021 that enable foreign workers more flexibility in the workforce and reduced the power that private employers had in the past. For example, expat labour can now travel and leave the country without the permission of their companies like before. A recent IMF paper praised such reforms and argued that such policies will make Saudi Arabia’s labour market more competitive and easier to attract talented foreign workers into the country. While I strongly believe that these labour reforms are a step in the right direction, I believe that numerous adjustments are necessary to truly equalize labour mobility and reduce unemployment amongst citizens.

More specifically, even with the current reforms, there are two major limitations that still make it more attractive from a private firm’s perspective to hire a foreign worker, rather than a similarly qualified citizen. First, foreign workers must still spend 12 months on the job before they can quit and switch to another private firm. Second, although expat labour can now apply to leave the country before their contract ends but once they leave, it will be difficult or impossible to reenter Saudi Arabia as a foreign worker. This latter provision in particular discourages foreign workers from leaving their employer before their contract ends, thus making them ‘less mobile’ compared to Saudi workers. As a result, even when labour costs and educational attainment are equal between two candidates, a private employer will arguably choose the candidate that can’t quit their job for the next 12 months (i.e., a foreign worker in Saudi Arabia).

The Bahrain case

In the introduction, I argued that Bahrain’s experience with eliminating all labour restrictions on foreign workers between 2009-2011 offers us an empirical example on the economic benefits of such reforms for both citizens and foreigners alike. By 2007, Bahrain’s unemployment rate amongst citizens reached 7%, which was considerably high given the country’s domestic population size. Additionally, around 81% of workers in Bahrain’s private sector were foreign. Therefore, it was puzzling for Bahraini policymakers that the private sector was constantly able to create jobs yet most employers preferred hiring foreign labour, over citizens.

To address this problem, Bahrain passed two major labour policies, which, to my knowledge, remain the strongest attempt across Arab countries to end the labour wage gap between citizens and foreign workers. First, in July of 2008, Bahrain increased the fees paid by private firms to hire a foreign employee from around $22/month to $49 per month. This was meant to disincentivize firms from hiring expat labour primarily for their low cost, compared to citizens. By Q2, 2009 Bahrain introduced a more crucial reform that allowed all workers regardless of nationality, to leave their job at any time or quit and work for another employer. This decision was implemented despite constant opposition from private firms that have been historically dependent on cheap foreign labour.

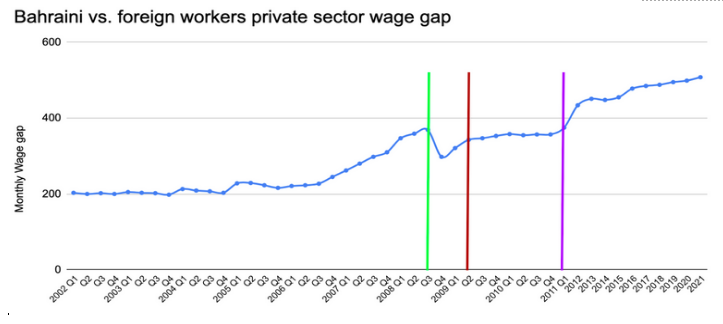

To illustrate the plausible impact of the two labour reforms, I compute the private sector wage gap between national and expat workers’ salaries from Q1, 2002 through Q1, 2021.2 In the graph, I highlight three main labour policies: 1.Increasing monthly fees on firms to hire expat labor (green line); 2. Granting all workers the right to quit their jobs and switch employers (red line); 3. re-introducing labour restrictions on foreign employees due to business pressure (purple line).3

The graph shows us that the labour cost gap declined immediately after the first policy (i.e., taxing firms for hiring foreign labor). The wage gap rose slightly before stabilizing again after introducing the policy to equalize labor mobility (red line). However, after two years, Bahrain introduced labour policies (represented by the purple line) that once again, restricted foreign employees’ mobility in the workforce. For example, foreign labourers were required starting in 2011 to complete 12 months with their current employer before they are allowed to work for another company in Bahrain, thereby making it again more attractive for firms to hire foreign workers. Intuitively, one apparent consequence of this policy adjustment has been the rapid rise in the wage-gap between nationals and foreign labour, from 2011 onwards. Furthermore, this policy change not only negatively impacted foreign employees, but also citizens, as it indirectly exacerbated their labour-cost disadvantage since 2011. Lastly, one might also wonder, what happened to unemployment amongst Bahraini citizens before and after the labour reforms were implemented? The domestic unemployment rate declined significantly from around 7% in 2007, to 3.6% in 2010. As a result, I further argue that once labour mobility became equal across all workers, private firms no longer had an incentive to hire expat labour in occupations where Bahraini workers were available.

In conclusion, despite differences in the private sector size between Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, the composition of the two labour markets is similar. The private sector in both countries is characterized by a large wage-gap between nationals and foreigners and a strong preference to hire foreign labour, with over 75% of workers as expats. Therefore, I believe that Saudi Arabia can gain from Bahrain’s experience in 2008-2011 by equalizing labour mobility, which will benefit all workers regardless of nationality. This in turn will not only boost incomes for foreign workers but will also reduce unemployment amongst citizens, thus providing economic gains for all labour in the private sector.

In conclusion, despite differences in the private sector size between Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, the composition of the two labour markets is similar. The private sector in both countries is characterized by a large wage-gap between nationals and foreigners and a strong preference to hire foreign labour, with over 75% of workers as expats. Therefore, I believe that Saudi Arabia can gain from Bahrain’s experience in 2008-2011 by equalizing labour mobility, which will benefit all workers regardless of nationality. This in turn will not only boost incomes for foreign workers but will also reduce unemployment amongst citizens, thus providing economic gains for all labour in the private sector.

1All data from Bahrain are publicly accessible through the Labour Market Regulatory Authority.

2This is calculated as the difference between average monthly wages for citizens and foreign labour. A large amount signifies a larger wage gap between the two groups.

3Labour market data in Bahrain from 2002-2010 are quarterly, but only annual data are available from 2011 onwards.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photo: Street in Manama, Bahrain. Credit: Francisco Anzola on Wikimedia Commons.