MSc student in Development Studies Harkiran Bharij writes on global education inequality, examining its root causes and what measures can be taken to provide children currently being left behind with quality education.

As the lecturers at 68 universities up and down the country continue striking in a plea to address the issues that are so deeply entrenched within the higher education system, it is important to remember what education sets out to do, and why it does not work for some.

Education has been referred to as a ‘fundamental human right’ by developmental agencies and organisations. Goal 4 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is devoted to education; it advocates for inclusive and equitable quality education that promotes lifelong learning opportunities for all. Despite this bid to make education equal and just for all, the reality falls far short of this. There is a clear divide in education between the Global North and Global South, with many in both missing out from the quality education outlined in Goal 4 of the SDGs.

The main problems: poverty

Perhaps, the most important reason why education doesn’t benefit all students equally is poverty. Recent World Bank statistics estimate that four out of five people live below the international poverty line (US $1.90 per person per day), and half of this number are children. This has resulted in adverse effects on their education with 70% of the global poor aged 15 and older having no basic schooling.

Even in the UK, one of the world’s richest economies, 4.3 million children and young people are trapped in poverty. This means that 30% of children, or nine pupils in every classroom of 30 are officially poor. Poverty also disproportionately impacts those from minority backgrounds such as African and Asian, showing how it interacts with race and ethnicity.

Things were going well before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, but 2020 became the first year in over two decades that saw an ‘extreme global poverty’ rise. The effects of the pandemic coupled with the forces of conflict and climate change have pushed over 100 million additional adults and children into poverty.

How does poverty affect educational experiences?

Especially in the Global South, research has shown how poor children are forced to ‘drop out’ of school as their parents cannot afford it. In 2017, the World Bank estimated that 61 million primary school children and 200 million secondary school children were forced to leave school.

Reasons for this include: A lack of finance, meaning that school fees cannot be paid; Parents needing the help of their children at home to support with cooking, cleaning and tending to animals; Bad influences such as drugs and alcohol; Sickness; Lack of school infrastructure; Lack of sanitary pads (for girls); Lack of proper guidance.

Gender inequality

The reasons to invest in girls’ education are manifold, including a transformation of the community and economy, enabling women to earn higher incomes and participate in decisions which affect them. However, unequal access to education is a major factor inhibiting girls from partaking in education and reaping these benefits. Gender inequality is seen throughout all levels of education, from skewed enrolments between boys and girls, to stereotypical course selection and poor career progression.

Gender discrimination is also a major issue worldwide, with girls and women often being left behind. Statistics show that 15 million girls of primary school age will never have the chance to learn to read and write in primary school compared to 10 million boys. In countries where patriarchal and traditional cultural attitudes are predominant, this is even worse. Research from Indian villages shows how parents are often less convinced about the value that education has for their daughters compared to their sons, with marriage and housework being the most important factors stopping them from completing school.

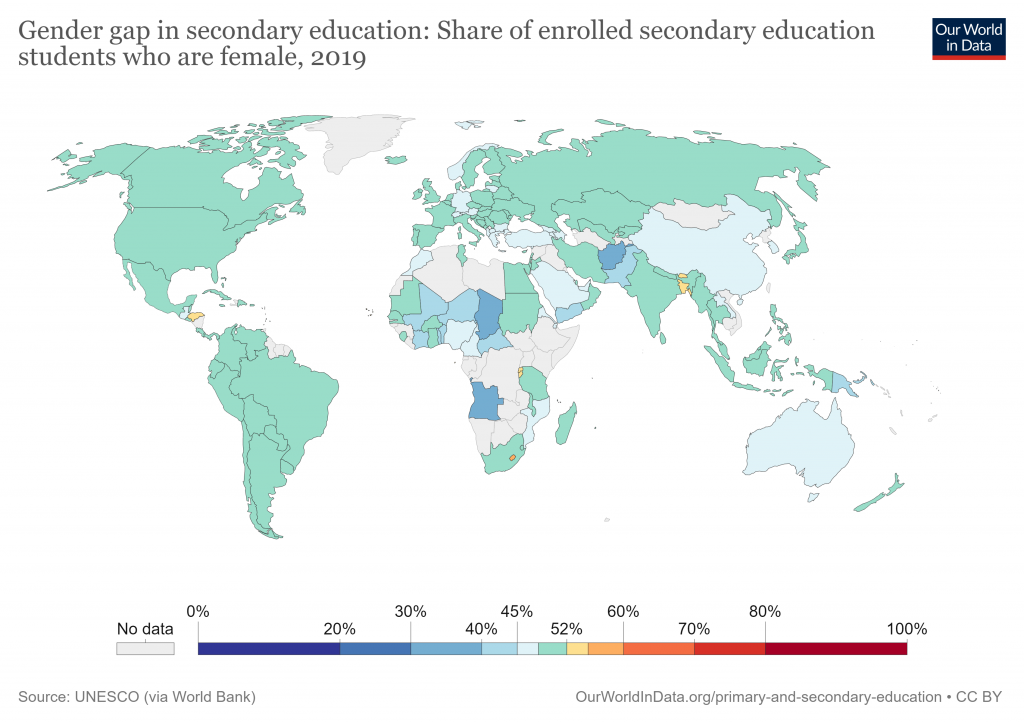

Schools are often not gender responsive either, with the safety, hygiene and sanitation needs of girls being unavailable. In 2019, it was found that 1 in 10 girls in Africa were forced to miss school when menstruating. The lack of access to sanitary products meant that they had to resort to using contraceptive injections to control them. This is not just limited to countries in the Global South; in October 2021, Plan UK found that nearly 2 million girls were forced to miss school because of their period. Overall, the impact of gender inequality on girls worldwide is vast and creates a profound gender gap in education.

This graph shows some promising trends, with 50% of all girls worldwide – both in the Global North and South – enrolled in secondary school education. However, some countries in Africa and Asia are well below this average, such as Angola and Afghanistan, respectively.

Teachers’ Expectations

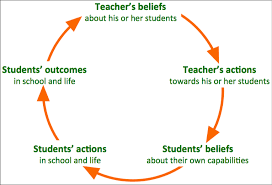

Compared to poverty and gender inequality, which often restrict children from accessing school, teachers’ expectations directly affect student performances. Rosenthal and Jacobsen’s 1968 study was the first of its kind to research this, branding it the ‘Pygmalion Effect’. In this, the expectations that teachers have of their students affects the way teachers interact with them, which ultimately leads to changes in students’ behaviour and attitude. It is a reinforcing cycle of self-fulfilling prophecies: if the teacher believes that a student can succeed, or believes they cannot, more often than not this view will come true.

How do teacher’s expectations effect students from minority backgrounds?

In the Global North, most teachers are from similar backgrounds: they are white, male and middle or upper class. The cultural attitudes that they have, along with the students they teach, are the same ones which are normalised within the system. Hence, by default, students who fit this profile are advantaged.

Research from New Zealand finds how teacher expectations of Māori students were significantly lower because of perceptions that they are low performing and that they come from families where education is not valued. The same study found how teacher expectations were higher than the actual performance of the Pacific Island and New Zealand European students.

Similarly biased expectations have been identified in research on gender and race intersections, with minority girls viewed negatively. Afro-Caribbean British girls are often given inadequate career advice, while the educational potential of Asian British girls is often seen as wasted because of early marriage.

The three reasons mentioned above provide a small and succinct picture of why schooling does not benefit all students. Poverty, gender inequality and teachers’ expectations are the most common factors but unfortunately, the list is extensive, including wars and other conflicts, violence, race-related issues, and many more. For education to truly benefit everyone, it is important that these issues are addressed and education systems adapted to make them accessible for children who are currently being left behind.

There are various ways in which education systems can be improved. Primarily, taking an ‘equity’ influenced approach may be more efficient than an ‘equality’ influenced one, wherein the differences between children are acknowledged and they are treated accordingly. Next, the cost of education can be reduced to ensure that more children can access it. Evidence from some African countries shows how this small action is beneficial in increasing school enrolment. Furthermore, school lunch programmes can also be implemented to support those who are hungry. Not only does this work to alleviate student hunger, but it also encourages regular school attendance. Educating parents also has an important impact on the education system; providing parents, especially those that reside within traditional communities, with information on the value of education could have positive effects on maintaining school enrolment (particularly for girls). Finally, within the system itself, access to adequate resources is key to success. Training and investing in teachers, in both the Global North and Global South is important in ensuring that children’s learning is up to date and that they are able to gain the most from the system.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Main Image credit: A Classroom in Madagascar. Image Source: Globalcitizen.org.