Meshal Alkhowaiter examines measures Saudi Arabia has taken to close the wage gap between its citizens and migrant workers and what lessons can be learned from policies implemented in Singapore.

Introduction

In 2018, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Development (MHRSD) introduced annual fees on all private firms that employed foreign labour. However, the fees varied depending on the number of citizens working in the firm (ie, firms with more foreign workers than citizens paid higher fees, and the sector in which the firms operate. For instance, firms classified as industrial and exporting firms were later fully excluded from expat levy fees. In April 2020, the MHRSD also exempted small and medium-sized enterprises (SME)s defined as having nine workers or less from the tax.

Despite the various labour reforms implemented by the MHRSD, the wage difference between foreign and Saudi workers remains stubbornly high, where foreign labourers earn 70% of the average income of Saudi workers with the same qualifications. In this article, I use Singapore as an example of a country that has successfully addressed the labour cost gap between citizens and foreign employees. Until 2017, Singapore relied heavily on cheap foreign labour who composed about 50% of its private sector. Similar to Saudi Arabia, Singaporean private firms historically preferred employing foreign workers, which has often meant replacing citizens with equally qualified yet cheaper foreign labour. To reduce its dependence on foreign workers, Singapore adopted several policies to bridge the labour cost gap between citizens and foreign labour. Some labour market policies such as nationalization quotas, and fees on foreign workers have been implemented by the MHRSD, but there are other effective policies that Saudi Arabia can adopt based on Singapore’s experience.

Has the labour cost gap changed since 2018?

Currently, Saudi private firms that employ more foreign workers than nationals pay a yearly tax of 9,600 Riyals (around $2556). The policy was originally implemented four years ago to eliminate a long-term hurdle that citizens have experienced in the private sector, competing with foreign workers who have equal qualifications and job experience but at half of the cost (see Hertog 2012, IMF 2018, and Alkhowaiter 2022). To address this ongoing challenge, the MHRSD has passed another major labour reform in 2021 that provides foreign employees with greater, albeit not full job mobility. The rationale behind both policies is that by raising the financial cost and equalizing the labour protections for foreign workers, private firms would gradually switch to merit-based, rather than cost-driven hiring decisions.

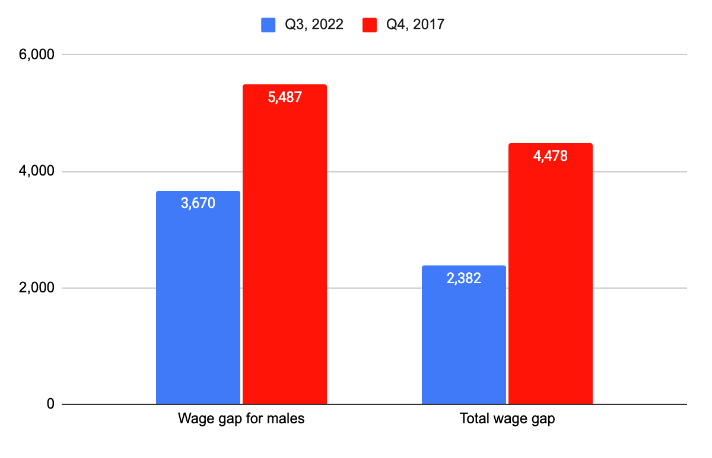

To assess the effectiveness of the ministry’s policies and whether it has lowered the labour cost gap between Saudi and foreign workers, I compare the wage gap based on average earnings between Q4, 2017 and Q3, 2022, respectively. I further control for educational attainment and strictly compare Saudi and foreign workers with a college degree. I choose Q4, 2017 as the baseline as it represents the last quarter pre- expat fees and compare this to the latest labour force data on Q3, 2022.

The good news for the MHRSD is that the wage gap between Saudi and foreign employees with a college degree has narrowed remarkably by around 33% or 1,817 Riyals per month. The outlook appears more positive when compared with the total labour cost differential, which decreased by 46.8% (see graph 1). In other words, aggregate figures suggest that taxing firms per foreign worker was associated with foreign labour becoming more expensive, which is presumably a good outcome for the MHRSD and Saudi workers. However, a closer look at the underlying causes of the shrinking wage gap between Saudi and foreign males tells us a less positive story as there has been a decline in the cost gap due to a stagnation in the average monthly wages for Saudi males between 2017 and 2022 and a 19% increase in wages for foreign male workers. The second reason should be less concerning for the MHRSD as it signifies a healthy job market where wages are growing over time, yet the former requires an in-depth analysis.

Graph 1. Average monthly wage gap between Saudi and foreign college-degree holders in Q4 2017 vs. Q3 2022.

Note: Each bar represents the wage gap amount in a given period.

What can Saudi Arabia learn from Singapore’s experience?

To reduce its reliance on mid-skill foreign labour, Singapore launched several labour policies to prevent firms from hiring workers primarily based on their low cost. Currently, all Singaporean private firms interested in hiring a skilled foreign worker must go through the S Pass programme, and provide sufficient evidence that they are hiring the worker for their specialized skills, and not cost. The programme has three main conditions, which address the roots of the wage gap. First, and most importantly, Singapore introduced an occupation-based minimum wage for all workers. Specifically, private firms are mandated to pay foreign labourers a wage equivalent to what the top-third of citizens are earnings in the same occupation. For instance, if the salary earned by the top-third percentile of citizens working in a Singaporean consulting firm is $2000 per month, then the Ministry of Manpower (MoM) will not allow a firm to hire foreign workers for any wage below this threshold. This condition creates both justice and economic sense because it protects citizens from the labour-cost disadvantage experienced by Saudi men in particular, who are strangled in a competition with both cheap foreign workers, and heavily subsidized Saudi females.

Second, the Singaporean MoM requires private firms to pay foreign labour based on their work experience. This again ensures that private firms are not replacing young citizens with more experienced yet cheaper foreign employees. Finally, to increase the quality of its workforce, Singapore requires all foreign labour to have completed their education from an accredited university. This requirement has benefits that extend beyond creating equitable labour market conditions, and has enabled Singapore to consistently rank as the world’s most competitive economy and third most competitive labour market. The latest administrative data from the MoM suggests that the number of mid-skill foreign workers in Singapore has decreased by around 8.2%, reaching 169K workers compared to 185K workers when the S Pass programme was introduced in 2017. As a result, one may infer that at least some of the departing foreign labourers were employed primarily for their low cost, and that once the MoM required firms to pay them wages equivalent to citizens, some were laid off.

In conclusion, I believe the Saudi MHRSD has introduced effective labour policies since 2017, which have lowered the wage gap between citizens and foreign employees as shown in graph 1. The labour reforms in Saudi Arabia have also coincided with both higher female workforce participation and the lowest unemployment rate in a decade. However, Saudi Arabia can further expedite the pace of its labour market reforms by adopting policies from countries that have faced similar challenges, such as Singapore. These policies may include measures such as:

- An occupation-based minimum wage where foreign workers earn a wage that is at least equivalent to the top-third percentile of Singaporean workers in the same industry,

- Restricting visas to workers from highly ranked and accredited universities, and

- Requiring firms to pay wages based on experience, which gradually increases over time.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photo credit: Construction workers in Singapore via JNZL on Flickr.