Decolonising global health requires challenging the widely accepted idea of ‘western medicine’. There is an urgent need to deconstruct this notion to level the playing field which would allow for North-South health development partnerships to be truly equal. MSc Health and International Development student Ziyaad Surtee suggests this can be achieved by adopting a historical approach.

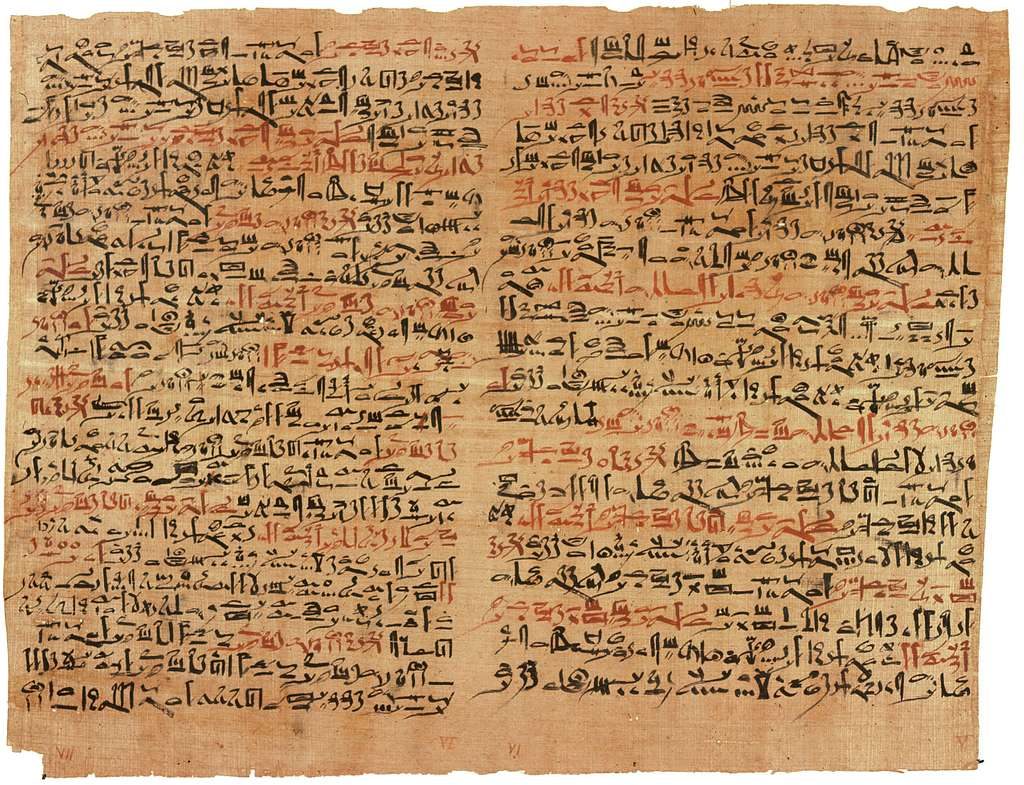

Recently, I came across an interesting document called the ‘Edwin Smith papyrus’ which is recognised as the oldest surviving trauma text in history. It contains accurate details on treating spinal injuries and dates back to the seventeenth century BC. The manuscript was written in ancient Egypt and predates Hippocrates (the ‘father of medicine’ and creator of the Hippocratic oath). As a result, I was led to critically consider the term ‘western medicine’ and the harmful impact it has. Ancient Egyptian scholars composed this important document yet it has been reduced to the name ‘Edwin Smith Papyrus’ after the antiquities collector who acquired it. This perpetuates the myth that medicine is western, when clearly historically it has not been. I do not intend to discredit western advances in medicine at all, rather to highlight where the same has been done.

One example that stands out to me is that of the polymath Ibn Sina who is considered the father of early modern medicine. He wrote the seminal work ‘al-Qanun fi al-Tibb’ or the ‘Canon of Medicine’ which discussed anatomy, physiology and also included a drug formulary. The book was translated into Latin in the 12th century and became a standard medical textbook in Europe. It was consulted in the Muslim world way into the 20th century. Despite such valuable scholarship, in academic literature, Ibn Sina’s name has been Latinised into Avicenna. This name conjures an image of a Roman philosopher in a toga, rather than the truth of a Persian scholar who wore a turban.

The same problem is seen with Al Zahrawi who was born in Al-Andalus at the time of Moorish Spain and worked in Córdoba. He is considered the father of modern surgery and authored the work ‘Kitab al-Tasrif’ which was used as a textbook in European universities. It included areas such as ophthalmology, orthopaedics and gynaecology. Additionally, Al Zahrawi pioneered internal stitching, described haemophilia and produced surgical tools which remain in use to this day. Again, in the academic literature, his name is Latinised to Albucasis.

It is also interesting to explore the history of obsessive-compulsive disorder (or OCD). This was argued to be first reported by Robert Burton in ‘The Anatomy of Melancholy’ in 1621 with further refinement occurring in the 19th century. However, it has recently been found that Abu Zayd al-Balkhi in the ninth century described the symptoms of OCD in his work ‘Sustenance of the Body and Soul’. His descriptions are found to be consistent with modern diagnostic criteria (The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5)). However, this scholarship has only recently been brought to light.

It is debated that the first university or institute for higher learning (Al-Qarawiyyin) was established by Fatima al-Fihri in Morocco in 859 AD with provisions made for female students to learn. Given the time period, this is a remarkable feat. There is also historical debate over the earliest evidenced medical degree (in 1207 AD) given at this university, which again would underline my point that ‘western medicine’ is a misnomer.

All of these above points aim to give an honest portrayal of the history of medicine which cannot rightly be called western. In fact, textbooks written from these scholars have been used in European universities. It serves to illustrate that knowledge has been transferred from east to west and history has been rewritten to give the illusion that this was not the case. This is a fundamentally harmful narrative that has implications till today.

It created the misplaced belief that western academia is superior. A paper found that 35% of 236 articles in the Lancet global health journal had authors associated with LMICs (lower middle income countries) whilst the majority were from high-income countries. As well as this, global health masters degrees are concentrated in the global north (19 in Europe and 17 in North America vs 1 in Africa, 2 in South-East Asia and 2 in the Western Pacific). This perpetuates the idea that the global north has a right to articulate solutions to the global south as there is a subconscious belief that western knowledge is more advanced.

When the possibility of providing anti-retroviral therapy to Africa during the HIV/AIDS crisis arose, the chief of USAID was opposed. In 2001, Andrew Natsios told US congress why he thought this was the wrong move, “If we had [HIV medicines for Africa] today, we could not distribute them. We could not administer the program because we do not have the doctors, we do not have the roads, we do not have the cold chain…[Africans] do not know what watches and clocks are. They do not use western means for telling time. They use the sun. These drugs have to be administered during a certain sequence of time during the day and when you say take it at 10:00, people will say what do you mean by 10:00?”. This prejudiced belief arose from the misguided notion that western medicine and knowledge is superior, which apparently gives one the right to dictate which countries deserve life-saving drugs.

It happened again during the recent Covid-19 pandemic where by April 2021, 80% of vaccines went to high-income countries with 0.3% going to people in low-income countries. This emphasises one undeniable truth – we have not learned.

The aim of this blog is to make steps in decolonising global health by adopting a historical perspective. It is clear that despite good intentions, global health remains colonised which results in harmful effects. Subconscious bias persists in academia and when translated into development projects leads to negative outcomes as the target population isn’t considered to know what is best.

There have been attempts to ameliorate this with North-South collaborative projects, which appear to be objectively good. However, they can never be equitable until the myth of western knowledge being superior is dispelled.

For me, this begins with giving credit where credit is due. It is Ibn Sina and not Avicenna.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Miniature of Ibn Sina, via commons.wikimedia.org.