Guest bloggers Heiner Flassbeck, former German vice-minister of Finance and Dr Patrick Kaczmarczyk, consultant at UNCTAD compare the developments in Argentina and Türkiye and argue that the only way to address the problem is through cooperative behaviour of the government, businesses, and trade unions – supported by reforms of the international monetary and financial architecture.

Since the election of a president who wants to drastically reduce the size of the state to “unleash the powers of the markets”, Argentina’s economy is once again at the forefront of economic debates. Javier Milei insists that there is no alternative to a radical market economy to lead his country out of decades of mismanagement.

In this article, we want to ask the simple question of how Argentina’s central problem, extremely high inflation, is to be tackled by the “markets”. Thereby, we use the contrasting example of Türkiye, which is also much discussed in the media, to show why it is almost impossible to return to moderate inflation anywhere in the world using the orthodox means of policy.

The status quo

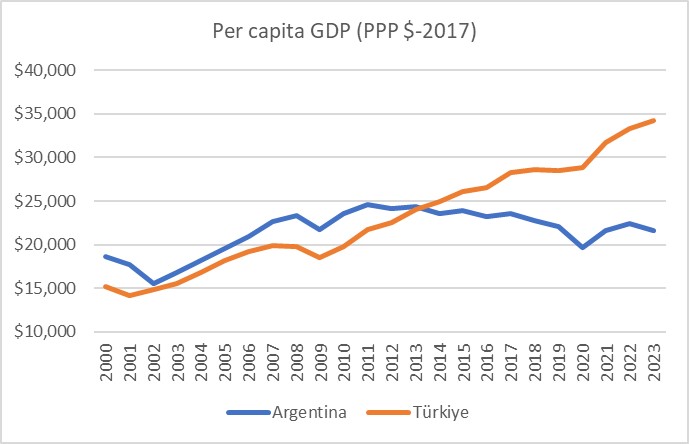

Looking at economic development in Argentina over the past decades, there is little doubt that the story is one of an almost continuous decline. In the first years of the 2000s, Argentina grew strongly because it had ended its major currency crisis in 2002 with a dramatic devaluation and exports exploded. However, after the global financial crisis of 2008/2009, the country was never able to return to a growth trajectory. Figure 1 shows the real GDP per capita in Argentina and, in comparison, Türkiye. Both countries have been struggling with high inflation for several years and seem unable to find a way out. However, the difference in real development is enormous.

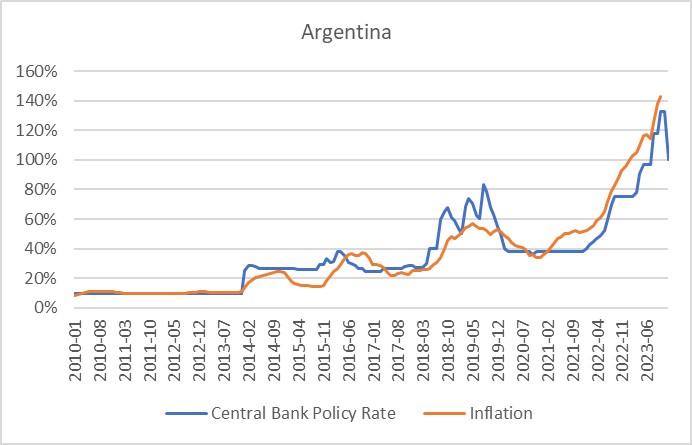

The key difference between Argentina and Türkiye lies in the different macroeconomic conditions and the policy responses to inflation (Figures 2 and 3). In Argentina, the central bank followed every swing in the inflation rate with an interest rate hike. During the 2010s, nominal interest rates remained mostly even above the respective inflation rates. According to the prevailing economic doctrine, enforcing such a positive real interest rate is the only way to successfully combat inflation – an approach that evidently failed in Argentina.

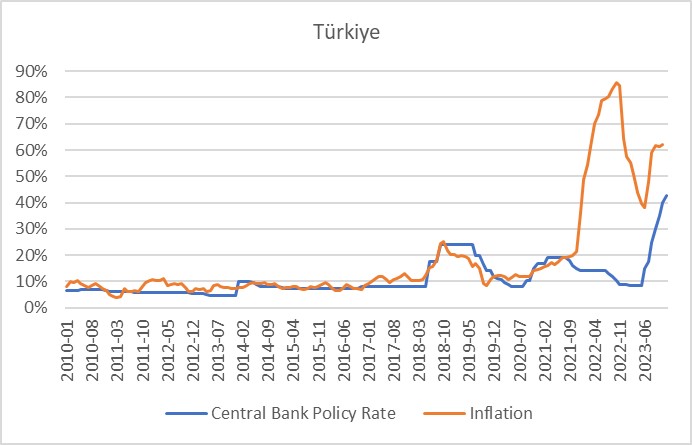

The case of Türkiye is quite different. Here, too, the initial roadmap was that interest rate policy should at least follow the inflation rate. However, at the end of 2021, the president decided that this policy was not appropriate due to its impact on growth and ensured that the central bank’s interest rate remained well below the inflation rate until the beginning of 2023. After two years, however, this experiment was abandoned because it was of course unable to prevent further inflation. Since mid-2023, Türkiye has returned to an orthodox interest rate policy and the interest rate is now above 40 per cent.

What triggered inflation?

The attempt in both countries to combat very high inflation with restrictive monetary policy and ever-increasing interest rates has failed. Even a deep recession, as in Argentina, and a significant slowdown in growth, as in Türkiye, have not led to a slowdown in the pace of inflation.

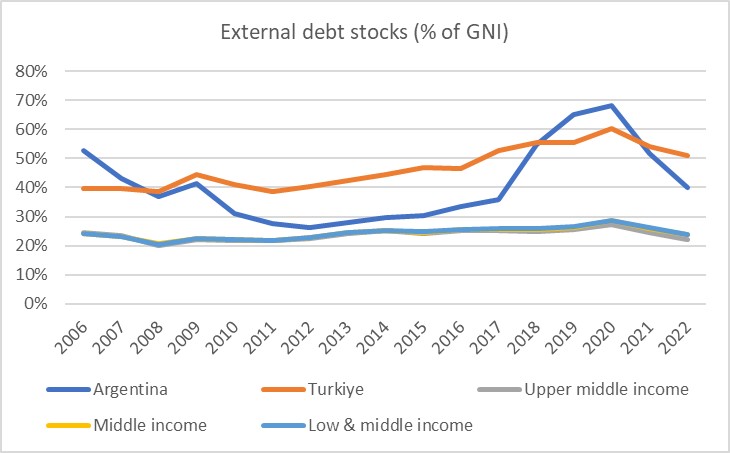

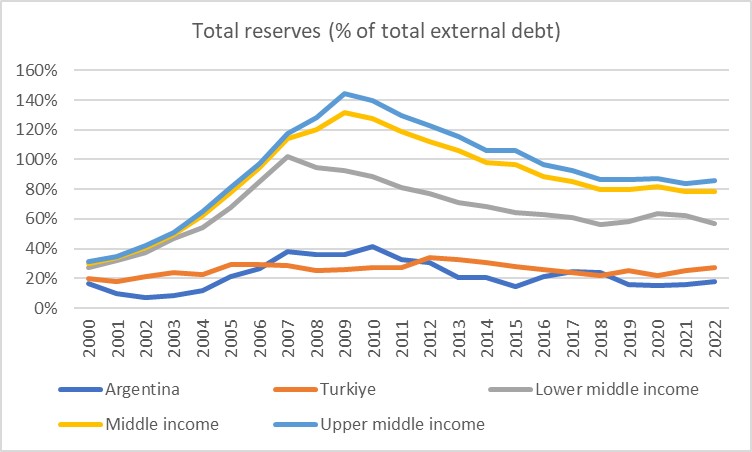

This is due to a wrong diagnosis of what causes inflation. It was not a lax monetary or fiscal policy that triggered inflation, but usually devaluation surges that impacted the domestic economy via imports. The three significant increases in interest rates since 2010 (2014, 2018 and 2022 in Argentina and 2023 in Türkiye) did not occur by chance almost simultaneously. The first significant interest rate hike at the beginning of 2014 followed the change in US monetary policy (taper tantrum) in the summer of 2013. The second increase in 2018 was also an attempt by the central banks to halt a spiral of devaluation, caused by an interest rate turnaround in the US. The same was the case during the early 2020s. The reason for the peculiar vulnerability and dependence of Argentina and Türkiye on global refinancing conditions is their very high levels of external debt, which is barely covered by reserves (see Figures 4 and 5).

Why does permanent inflation occur after a shock?

A devaluation of the domestic currency usually creates inflationary pressure, as imports become more expensive and confidence in the domestic currency is lost (which, in turn, has an impact on wage development as workers demand higher nominal payments in the domestic currency). Those who receive their salary in pesos or lira exchange what is left after taxes into foreign currency or invest in tangible assets, such as cars or real estate. Bank deposits are also often held in US dollars. In Türkiye, almost half of the deposits in private household accounts are denominated in foreign currency. In Argentina the figure is closer to 20 per cent – although the amount of savings in foreign currency outside the banking system is likely to be significantly higher.

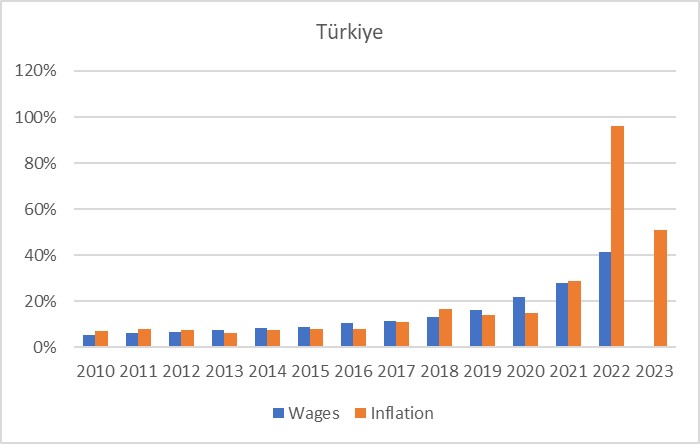

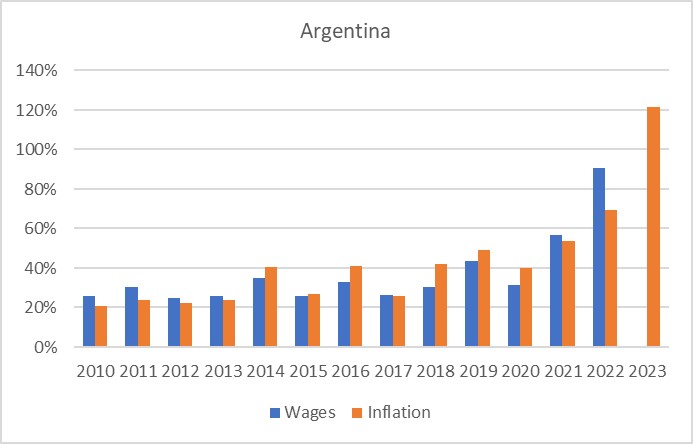

If prices start to rise after a shock, there is a reaction in wages that sets off an inflationary spiral. The minimum wage development in Türkiye is a case in point. In January 2023, the government raised the minimum wage by 55 per cent, in July last year by another 34 per cent and in January 2024 by a further 49 per cent. The dynamic that follows is always the same: Because inflation is high – for whatever reason – wages tend to follow, as otherwise, people will starve, and the economy will collapse due to a lack of demand. At the same time, however, inflation is and remains high if wages are constantly rising. Price increases and wage increases are mutually dependent (see Figures 6 and 7).

What needs to be done

Under such conditions, both labour and capital (as well as the state as the minimum wage setter) block each other because no one can trust that the other side will do the same as they do. The only way out of this prisoner’s dilemma (whoever moves first loses) is if the two sides (companies and trade unions) are persuaded by a third party (the government) to negotiate an exit from the vicious circle of ever new price-wage-price spirals. This would resemble a sort of currency reform without necessarily having to replace the currency. The government must make it clear that it will brutally stop the previous spirals using a wage and price freeze if the collective bargaining partners do not agree to negotiate wage increases based on a new low inflation target.

The activation of wage or income policy by the government is the only way to combat permanently high inflation rates. No “market” can stop a price-wage-price spiral once it has started. Restrictive monetary policy is pointless and even counterproductive when price increase rates have become so entrenched. Stifling the economy further reduces the chances of winning over the companies and trade unions that are needed to find a solution for talks with the government. All attempts to ensure the “recovery” of public finances through restrictive fiscal policy are also pointless, as it does not effectively address the source of the actual problem.

For policymakers, it is important to realise that stubborn inflation is always and everywhere a wage problem. Consequently, it is always a question of politically breaking a vicious circle of price increase shocks and subsequent wage adjustments. With the conventional means of monetary and fiscal policy, this is not possible. Moreover, to keep the external value of currencies as stable as possible, particularly in the countries of the global south, the world’s central banks should intervene in the foreign exchange markets to ensure orderly currency revaluations and devaluations occur. This is essential to curb the herding in financial markets, which often triggers the original inflationary spurts, fuels panic, and leads to an extremely challenging environment for fighting inflation.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and do not reflect those of the International Development LSE blog, the London School of Economics and Political Science, or the European External Action Service. The blog is based on the author’s dissertation.

Image credit: President Javier Milei, Source: Mídia NINJA

Argentina is a case apart. Contrary to Turkey it does not have a functioning currency: The Argentine peso is neither means of exchange nor store of value. Every major transaction is priced in USD. The private sector is dollarized to a large degree; monetary savings are held outside the domestic banking system and/or offshore. In this context the banking system (deprived of savings) cannot act as the intermediary between savings and investment. There is no credit available with medium to long-term maturities. Bread-and-butter credit products, such as mortgages only exist for a tiny segment of the population.

In short, there no trust in domestic monetary and financial policy-making. The ideas mentioned in this article cannot work in such an environment. The state needs to create conditions conducive for trust to return. Milei’s confidence shock measures might be a way to achieve this. A majority of the electorate appears to have accepted that the country needs radical change.

Both Turkey and Argentina are fairly accurate examples of the fact that Keynesian economic regulation is becoming a thing of the past as a post-industrial methodology. The information and digital revolution with the growing vastness of AI will still provide that economic methodology, that new paradigm, which is still in its infancy. I dare to suggest that the blockchain and what we call “digital assets” are the primary manifestations of the AI Economic Paradigm. I must add that the genesis of “cryptocurrencies” gives hope for a new worldwide equivalent of value, but their modern form, full of opacity, and therefore money laundering and other criminalization, must be overcome.