Mexico has a chequered history when it comes to elections, with its electoral integrity occasionally coming under question. Here, Miguel Angel Lara Otaola assesses Mexico against the Perceptions of Electoral Integrity Index and analyses recent elections as well as the recent problems faced by the country from the disappearance of 43 students last year to the recent escape from prison by the top drug lord in the country.

Historically Mexico has long experienced controversies over problems of electoral integrity, including malpractices of vote-buying and intimidation. The most serious issues, which, amongst other factors, guaranteed the PRI’s predominance, were thought to have been corrected during recent decades, although at the same time problems of narco-crime’s involvement in politics have resurfaced and the 2012 Presidential elections saw some street protests over allegations of voter corruption.

In the light of this history, on January 2014, Mexico’s Congress approved far reaching political and electoral reforms. This involved a number of constitutional changes and a new Electoral Code. Amongst other things, it allowed for the formation of coalition governments, increased checks on the Presidency, expanded voting rights for citizens living abroad, and included special provisions for achieving gender parity in Congress. Moreover, it introduced the participation of independent candidates and allowed for the re-election of law makers.

The electoral reform enacted substantial changes. First, the Federal Electoral Institute (IFE) was transformed into a National Electoral Institute (INE). This new institution is in charge of organising federal elections (for the Presidency and Congress) and local elections (in coordination with 32 existing state election commissions). As a national body, it is now in charge of overseeing political party finance at the national level and of appointing the members of the country’s local election commissions. Furthermore, the reform changed the structure of INE’s Council (by adding two Councillors), strengthened its auditing powers, and increased sanctions for violations to the election code, including more provisions for the annulment of an election. In short, all these represented a significant evolution of Mexico’s electoral system.

The primary stated aim of this change was to improve election integrity, especially confidence in electoral processes. In particular, as argued by its makers, the change from IFE to INE would bring local elections up to the internationally recognised standards of federal elections. Lorenzo Córdova, President of INE said that the reform sought to strengthen elections in all states.

Despite this, it is unclear whether the reform will achieve its goals. In particular, data from expert Perceptions of Electoral Integrity (PEI) shows that in the 2012 Presidential election the country’s integrity score was 62 out of 100 points. By contrast, after the changes were implemented, in the 2015 legislative election, the score was 52. This is a modest but statistically significant drop in expert evaluations (R. .33, N. 34, P=.056). Moreover, this was not simply the difference between the types of contest, since legislative elections are usually evaluated slightly more highly by PEI experts than executive contests.

In terms of relative global position, out of 153 elections evaluated between 2012 and 2015, this meant that Mexico dropped from position 55 to 95. This score is obtained from experts that monitor the quality of an election based on 49 indicators covering 11 components of the electoral cycle (from election laws and voter registration to election results).

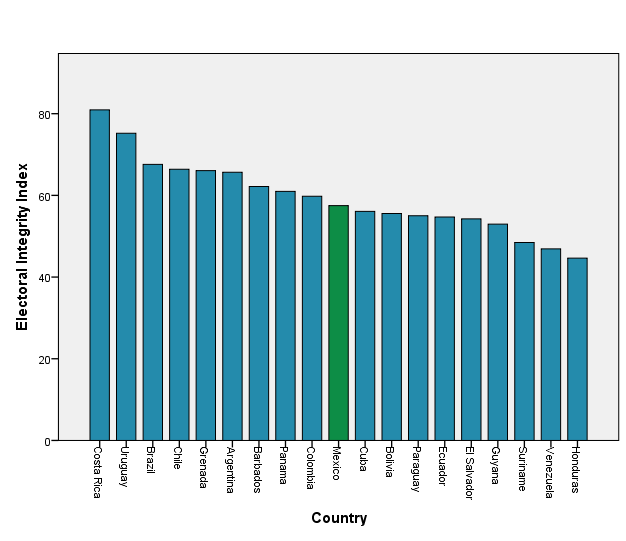

At the country level, Mexico ranks 54th of 125 and obtains a score of 57, which places it in the middle of the Latin American and Caribbean region (See Figure 1). Outside the region, countries with similar scores are India, Serbia, Ghana, Indonesia and Hungary. States such as Tunisia, Mongolia, Lesotho and South Africa – all of which face substantial challenges in terms of their electoral infrastructure – fare better than Mexico.

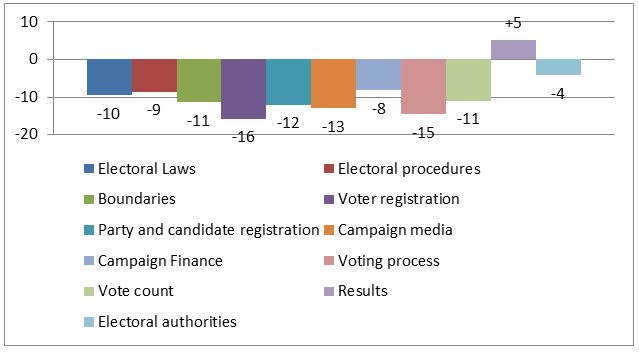

Specifically, if we deal with the eleven components of the index, all but one (election results) have slightly decreased for Mexico. Out of these, however, only the drop in voting processes is statistically significant (P=.000) while the drops in voter registration, campaign media and vote count are significant but only at a 10% threshold. By contrast, evaluations of electoral results improved, largely due to the fact that the 2015 elections were perceived as being less challenged and having generated fewer protests. Figure 2 shows the PEI score changes for all the parts of the electoral cycle.

Figure 1. Electoral Integrity in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Figure 2. Changes in Electoral Integrity. Mexico, 2012-2015.

The overall drop must not be considered a direct effect of the recent political and electoral reform as many other factors may be at play, and the general performance of the government can affect trust in other institutions, such as electoral processes. And these past two years have not been especially rosy for Mexico. To start with, on September 2014 a group of 43 people from the Ayotzinapa Teachers Training School were attacked and disappeared by municipal police, never to be heard from again. Soon after, a scandal erupted surrounding the buying of a multi-million-dollar house by the country’s first lady. Many other similar events have followed. And, if this was not enough, in July 2015 the top drug lord leader in the country Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzmán escaped (for the second time) from a high security prison.

As a result, support for the political system has suffered greatly. According to the PEI experts, in the last three years confidence in the government, the parliament and the courts has dropped. Out of these, the drop in confidence in government is the only statistically significant (P=.054). While in 2012 confidence in the government was the highest amongst the three institutions (5.14 points on a 1 to 10 scale), in 2015 it was the lowest (3.8 points). Moreover, when tested further, confidence in government among Mexican experts were strongly and significantly related to Perceptions of Electoral Integrity, even after controlling for several other factors, such as the expert’s background (age, sex, education, and whether they are based in the country or international).

Elections are about technical accuracy – but also about broader perceptions and beliefs. They do not happen in a vacuum, but they are embedded within a wider political system. A ´below average´ election organised in a country with a stable and legitimate political system has much more chances of being seen as credible than a technically perfect election in a country with a fragile –or momentarily weakened- political system. Let us hope that the storm Mexico is living passes swiftly.

This piece originally appeared at the Democratic Audit of the UK blog before being published on LSE’s USAPP blog.

Featured image credit: OneWorld Nederland (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Note: the views expressed here are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the position of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

_________________________________

Miguel Angel Lara Otaola – University of Sussex

Miguel Angel Lara Otaola is a PhD Research Student at the University of Sussex. His research question is “When, where and under what conditions are electoral results accepted?: A global comparative study”