Widespread corruption and an inability to tackle grave social and economic problems left Salvadorans deeply disappointed with the post-war governments of both the conservative ARENA party and the left-wing FMLN. Through a combination of necessity and invention, Nayib Bukele was able to channel this discontent into a stunning election victory that ends the two-party alternation in place throughout the postwar period. But following his inauguration on 1 June, Bukele should beware that his own vague plans will face the scrutiny of a vigilant and distrustful electorate, writes Ainhoa Montoya (School of Advanced Study, University of London).

Widespread corruption and an inability to tackle grave social and economic problems left Salvadorans deeply disappointed with the post-war governments of both the conservative ARENA party and the left-wing FMLN. Through a combination of necessity and invention, Nayib Bukele was able to channel this discontent into a stunning election victory that ends the two-party alternation in place throughout the postwar period. But following his inauguration on 1 June, Bukele should beware that his own vague plans will face the scrutiny of a vigilant and distrustful electorate, writes Ainhoa Montoya (School of Advanced Study, University of London).

El Salvador’s 2019 presidential election represented a rupture on many fronts. The clear victors were 37-year-old advertising executive Nayib Bukele and his New Ideas party, formed just a matter of months earlier, but their victory had a wider significance. Not only did it signal a break with the two-party system that has dominated the country’s postwar politics, it also contributed to the ongoing dissolution of the highly polarised left-right divide which emerged from the war and pitted the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front (FMLN) against the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA).

Is Salvadoran political culture losing its wartime roots?

As I argued in my recent book The Violence of Democracy: Political Life in Postwar El Salvador, the electoral discourse and tactics of both ARENA and the FMLN have contributed to the reenactment of latent wartime conflicts by fomenting Cold War-related passions and fears – and even aggressive behaviour – amongst their core supporters. While the 2009 presidential election was itself a significant turning point, handing power for the first time to a left-wing party formed out of a guerrilla movement, the 2019 election has just as clearly shifted El Salvador’s political culture away from its wartime roots.

On 3 February 2019, Nayib Bukele was elected with 53.1 per cent of the vote, which is more than all of the other parties could manage put together. He was also the winning candidate across the entire country, in all fourteen departments.

He ran as a candidate of the conservative Great Alliance for National Unity (GANA) party, but this strategic alliance was really his third choice. His own New Ideas party had been created too late to be registered, whereas his second choice, the centre-left Democratic Change party had been controversially eliminated by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. As predicted by the polls, the results of the 2019 election reaffirmed the trends revealed by the 2018 municipal and legislative elections.

The two main postwar parties, the conservative ARENA and the left-wing FMLN, saw their support significantly reduced. ARENA, which ran in a coalition with other conservative parties, received 31.7 per cent of the vote. Meanwhile, the ruling FMLN plunged to 14.4 percent, the party’s worst electoral performance since its first participation in 1994 and less than a third of its vote share in the first round of the 2009 and 2014 elections. Steep levels of voter abstention were also highly significant, with a figure of 48.1 per cent more comparable to the war and postwar eras up to 2004.

By around 9pm on election day, early returns were already signalling a clear win for GANA, and an exultant Bukele declared victory soon after. In his victory speech and later again from Plaza Morazán in central San Salvador, he proclaimed the start of a new era, where El Salvador had “turned the page of the postwar era, and we can now start to look towards the future.”

Were his words simply a rhetorical means of breaking with the immense disaffection of the recent postwar past and presenting himself as the leader of a new era? Or was he recognising a genuine epochal shift in El Salvador?

The decline of ARENA and the FMLN

In this election, Nayib Bukele managed to shed light on the coalescence of the ARENA and FMLN governments, in terms not only of their electoral behaviour and socioeconomic policy, but also of their corrupt practices.

The imprisonment of former ARENA president Antonio Saca for illicit enrichment and the fleeing to Nicaragua of the nation’s first FMLN president Mauricio Funes to avoid prosecution in El Salvador are only the most visible symbols of the country’s deep-rooted institutional corruption. Bukele wisely capitalised on the entrenched corruption of the two main parties in his electoral campaign, even going so far as to promise to create an international anti-corruption commission for El Salvador along the same lines as the Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG).

Many Salvadorans that I interviewed made clear that they were voting for Bukele because ARENA and FMLN were essentially ruled out by their leaders’ disappointing conduct. Given the salience of party loyalty among FMLN voters in the postwar era, the fact that in 2019 so many formerly core FMLN voters decided to vote (and even campaign) for Bukele – or at least to abstain – speaks to the extent of their disaffection with party politics. Though not to the same extent, the same was true for ARENA loyalists, and this was reflected in the final results.

Unlike in 2009, this was not an election characterised by hope. For many the 2009 victory of the FMLN showed that an alternative political project, and one which had historically embodied the possibility of a socially just future, could gain access to power. The decline of this project left its backers defrauded and deflated.

Like the ARENA government before them, the FMLN’s two consecutive governments resorted to “firm hand” security policies but remained unable to address the sky-high levels of insecurity that push so many out of the country every year. They maintained or even promoted neoliberal policies and regulations, not least through the 2013 Public-Private Partnerships Law and the more recent proposal for low-regulation, low-tax Economic Special Zones that intend to capture foreign direct investment. And they also failed to meet overdue commitments on justice and reparations for wartime human rights violations. Rather, some in the FMLN leadership enriched themselves through the development of their own business ventures.

New channels for political discontent

From 2014 onwards, and partly due to legal limits on political propaganda, traditional territorial strategies like candidate visits to municipalities and door-to-door canvassing began to decline. Electoral campaigns increasingly moved from the streets to social media, allowing a diversification of messages beyond the wartime polarities of ARENA vs FMLN.

With the emergence of Nayib Bukele, the digital domain became even more central, not least because Bukele was unable to exploit mainstream media to his advantage. The dominant print media, owned by conservative media moguls, were highly supportive of ARENA’s candidate. Indeed, given their aggressive editorial postures during previous campaigns, in 2019 they were surprisingly and strikingly benevolent towards the FMLN as well.

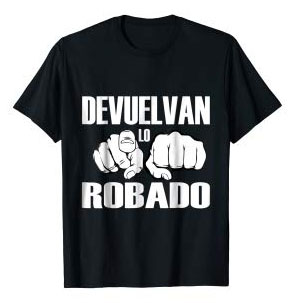

Conversely, they were openly critical of Nayib Bukele, most likely in an attempt to maintain the status quo of two-party alternation. But with internet-capable smartphones now widespread, Bukele’s campaign was able to mobilise many voters through social media, especially the young. Social-media users themselves even generated politically charged content reflecting popular political disaffection, with viral messages like #DevuelvanLoRobado (“Give back what you stole!”) making it out into the streets.

Nayib Bukele’s victory and the 2019 election thus represent an important shift away from an electoral politics that was highly mediated by wartime identities. It remains uncertain, however, what the future holds under his leadership.

Beyond Bukele’s inauguration on 1 June

Details of Bukele’s plans, their financing, and their means of implementation have been scarce, and during the campaign Bukele was also tight-lipped about the possible composition of any future cabinet.

Moreover, Bukele attempted to distance himself and his New Ideas party from GANA during the campaign, but as a new party New Ideas lacks any representation in the national parliament. And given the animosity of traditional parties towards Bukele, it is unclear how he will govern in an ARENA-dominated Legislative Assembly except through executive decree or temporary alliances and trade-offs.

One strategic but risky option would be to try to hold on until the next legislative election in 2021 while blaming other parties for any inability to pass legislation or get annual budgets approved.

Overall, what is most novel about his ascendance is that a majority of Salvadorans are clearly no longer willing to invest their hopes in a single candidate or party simply out of historical loyalty.

If anything, then, it was a pragmatic view that predominated in El Salvador’s 2019 election. Salvadorans have shown, whether through their social-media campaigns or their votes, that they are ever vigilant. Bukele would do well to remember that they could remove him just as easily as they elected him if he fails to deliver on his promises or engages in the same corrupt practices that undermined previous governments.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting