Sources of inequality may have changed since the colonial era, but its scale and impact continue to shape Barbadian society, writes Collin Constantine (Kingston University).

Sources of inequality may have changed since the colonial era, but its scale and impact continue to shape Barbadian society, writes Collin Constantine (Kingston University).

The renowned Barbadian historian Sir Hilary Beckles has recently argued that the white inheritors of The First Black Slave Society remain both dominant and unrepentant in today’s Barbados. For all the de jure political power that black descendants have achieved, de facto economic power has not shifted. His view is supported by my own research, which reveals new evidence of how this old colonial oligarchy in Barbados has transformed itself into a post-colonial oligarchy.

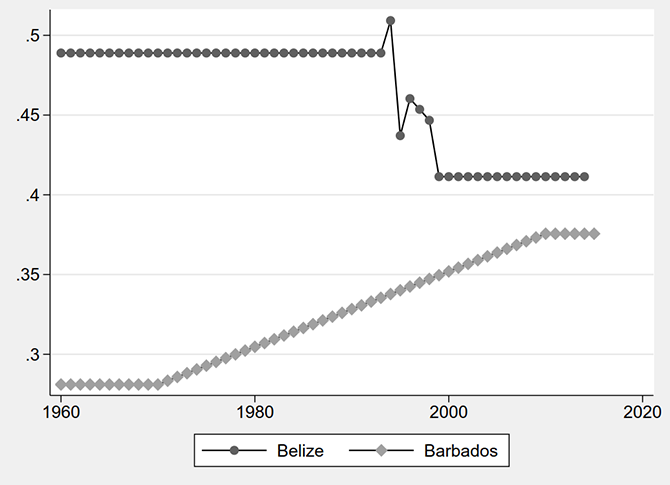

As of 2015, the average household income of the richest 10% in Barbados was 3.7 times that of the general population, while in 1960 this decile received only 2.8 times as much. This trend is even more pronounced for the top 1%, the elite of the elites. In 2015 the average household income of Barbados’ richest 1% was 10 times the average, whereas in 1960 it was just four times. This clear concentration of top incomes shows that growth in Barbados has been especially extractive, but what has changed in how elite power is maintained to enable this shift?

During the colonial era large landholders represented only about 7% of total landholders, but this group owned 54% of all property (slaves) by 1680. During the post-emancipation, pre-independence period (1834-1966) the social structure was maintained principally by the Contract Law, which kept workers in low-paid, landless tenantry until its repeal in 1937. Elites also joined forces to prevent the breakup of plantations and subsequent sale to former slaves, as well as opting – uniquely in the Caribbean – not to abolish its system of elite representation in favour of Crown Rule during the latter half of the 19th Century.

At the outbreak of World War II, Barbados remained essentially the same as it had been three hundred years earlier, only instead planters and slaves, society was now divided into planters and a free but landless population. By 1970 the top 10% of landholders are estimated to have owned 77% of the land.

More recently, Barbados has become one of the most important offshore financial centres in the Caribbean and one of the world’s top 15 according to Oxfam. Just as in the USA, Britain, and other industrialised economies, there is a link between financialisation and the growth of top incomes, with the industry’s particular ability to support “super salaries” a clear driver.

Of course, Barbados’ status as an offshore financial centre also contributes to rising inequality in Western Europe and the USA by allowing wealthy foreigners to shift income and wealth into a low-tax jurisdiction. While OECD countries are attempting to reclaim their “hidden wealth”, Bajans face growing inequality alongside austerity measures and weak tourism.

How does the idea of Barbados as a beacon of democracy in the Caribbean persist in spite of these facts?

In part, this is the same issue studied in other contexts by Thomas Piketty:

“When you have large wealth, you cannot just consume like other people. You start to consume influence, consume politicians, consume academics, you consume power; this is what high wealth is here for.”

The enormous concentration of income in Barbados historically meant that the most powerful and prestigious positions were reserved for colonial elites. In present-day Barbados, economic elites use grants, media ownership, campaign contributions, and so on to influence public policy, public opinion, and key actors to forge societal buy-in on policies that protect and reinforce elites’ economic interests.

Even more than in OECD countries, part of the problem is a lack of transparency about top incomes in Barbados, with a severe lack of studies on wealth and income distribution. But this is compounded by deliberate attempts to shift the blame onto the most visible participants in the local economy, namely migrants.

Like Mexicans in the US and eastern Europeans in the EU, the Guyanese have been scapegoated in Barbados, with raids and deportations increasing despite a commitment to the free movement of peoples within the Caribbean Community. This discrimination is so well known amongst the Guyanese community that it has spawned the term “Guyanese bench”, which describes especially slow and often unsuccessful entry process for Guyanese nationals at Barbados’ Grantley Adams International Airport. As with Trump’s Mexico border wall or anti-immigration discourse during the Brexit campaign, this distracts from the underlying issue of wide and widening inequalities of income, wealth, and power.

Overall, despite an appearance of calm stability in Barbados, which has produced the nickname “Little England”, there is discontent welling beneath the surface. But a lack of clear data about wealth and income distribution, combined with the associated political inequalities, undermines attempts to channel social anger. Until this spiral of growing inequality is arrested, the poor will continue to shoulder the greater burden of economic adjustment via austerity, whereas massive capital and wage gains will continue to go those who need them least.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This article draws on the author’s paper “A Community Divided: Top Incomes in CARICOM Member States” (2017)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

Collin Constantine – Kingston University

Collin Constantine – Kingston University

Collin Constantine is a PhD student in Economics at Kingston University and a Member of the Political Economy Research Group (PERG). His dissertation investigates the determinants of the Eurozone current account imbalances but his interests include institutions, inequality, development economics, and new political economy. Follow him on Twitter at @collin8818.

The author is on point. Great job and writing. It’s what most people are afraid to admit aloud and always comes under major fire from the representatives of the elite.

Logic vs fact etc etc mumbo-jumbo ‘I’m smarter than you’ nonsense is irrelevant when ppl are suffering.

Barbados is a joke. Blatant lies to the public, unpunishable fraudulent activity by government officials and their social partners, a downright erosion of political integrity; impossible inhumane food prices, tax sodomization, gas rape and the continuation of an insulting salespitch that the Government cares about the citizens.

It’s amazing to me that people can ‘intellectualise’ and ‘pick down’ the authors’ mechanisms but didn’t have an outlook on the actual point which is way more dire than a misrepresented timeline.

But why should those who are living good complain?

Great writing again!!!

A pity his analysis on land ownership stops in 1970, in the intervening 50 years I suspect things have changed dramatically. Both with the growth of the middle class via free education and also with legislative changes like the Tennantry’s Freehold Act.

Also the paper could be strengthened by including not just upper income as a multiple of the average, but what has the growth of the average been in the same period.

Karl Watson. The black middle class has been bludgeoned by the astronomically rising cost of living , draconian personal and property taxes with no cushion or safety net as Covid ravished the economic. Wealth disparity between sociology economic classes will increase. Colonialism irrelevant

Geoffrey Brewster 20 August, 2017 at 5:09 pm – Reply

While I agree with the author’s comments, the absence of supporting data for the “haves” weakens his arguement.@

We have much infomation and names to support this blog writter, But we seem to be block from posting the Names of Person in this mess,

I I think the commenters have quite articulately outlined the flaws; beyond this there is the reality that not only is there more data neede, but also more of this type of analysis… which brings us to it’s main theses, which lived lives in Barbados might bear out to be true: how do progress?

This article is misleading in many respects though it does contain some kernels of truth. The author includes some details from times as divergent as 1680, 1937 and 1970. The plantation based society of those times is no longer in existence. The planter and merchant class of those times is now extinct. Sugar is moribund and the society created by sugar has vastly changed since independence. Other commentators have pointed out the weakness in analysis caused by inadequate data sets. The single largest class in Barbados today is the black middle class which has grown enormously since independence instead of shrinking as siggested. Professor Richard Drayton in his critique is spot on.

EXTRAPOLATION vs ANALYSIS

Extrapolation is a valid form of inference, but it is often rightly criticized as the weakest form of logic. This writer fails to make the distinction clear between opinion and fact, simply because he generalizes from a few specific data points to make some rather wide pronouncements. This is inductive reasoning and prone to error. The writer would have been more believable were he to have used deductive reasoning or analysis of a REPRESENTATIVE field of knowledge to make a few unassailable pronouncements. In other words a more diligent, (admittedly time-consuming,) body of research would have made his conclusions more believable.

What is above is true, a lot of cover up fraud and Ponzi also in Barbados that leads to this type of Notice. Land fraud and Banking fraud on going, Laundering at all levels,

Much of this article is relevant. However, while the author states specific numbers with respect to income inequality, he states that there is “a lack of clear data about wealth and income distribution”. This certainly undermines his thesis. Without strong supporting data it is not possible to make a strong case.

While I agree with the author’s comments, the absence of supporting data for the “haves” weakens his arguement.

This is a lot of heavy analysis to lever on what is actually a very weak underpinning data set. I have read the underlying research paper https://www.researchgate.net/publication/316494080_A_Community_Divided_Top_Incomes_in_CARICOM_Member_States

and think this is a case of a political economist trusting quantitative indices when a lot more qualitative thinking needs to be done before they provide an accurate grip on the social reality. The reality is we do not have good indices for real incomes in Barbados, and the survey data is poor. The proposition made in passing that “since the 1970s, the middle class in Barbados has been shrinking” is manifestly absurd to anyone who knows this society in which the emergence of a black middle class, property owning and invested in high consumption, is one of the key stories of the 1970-2000 period. Barbados is a highly opaque society, particularly where it comes to wealth and incomes. The proposition (p 21) that Barbados was a “low mortality” country is patently untrue: we know, for example, that infant mortality was in the 200+ range, far worse than even malarial British Guiana in the 1918-40 period. The theory p. 22-23, that the economic elite of 21st century Barbados derives from the old planter class is empirically false : it was post-independence public spending on roads and infrastructure, and the rise of a high consuming large middle class which created the opportunity for the rise of the current Barbados wealth elite, many of whom came out of the poor whites, the ‘red legs’ eg. the Goddard family (which made its wealth on supermarkets and department stores principally), Kyffin Simpson (car dealerships), COW Williams (construction, in particular on public projects, combined with land speculation). There is certainly extraordinary inequality of wealth and income in Barbados, but it is the task of an empirical social science to actuallly investigate this and map it accurately, rather than merely gazing through the Piketty lens at what is a very poor data set.

I am a Natural Scientist (Biologist) and not a Social Scientist and therefore not capable of the kind of analysis that you have done. But you have expressed it in a way that is clear and with which I agree.

Well done. You are on point. The more things change. . . Take a look at the Barbados of 1937 .