Mexico City’s EcoBici bike-sharing scheme systematically broke down social barriers to enable the introduction of a new mode of public transport. Naima von Ritter Figueres (LSE International Development) analyses its success and considers whether this approach could work in other megacities around the world.

Mexico City’s EcoBici bike-sharing scheme systematically broke down social barriers to enable the introduction of a new mode of public transport. Naima von Ritter Figueres (LSE International Development) analyses its success and considers whether this approach could work in other megacities around the world.

Most cities have been shaped by the car over the past few decades. But heavy traffic, air pollution, safety hazards, and loss of public space, social cohesion, and economic competitiveness are all associated with an ever-increasing and unsustainable dependence on this form of transport.

A growing number of cities are therefore turning their attention to the humble bike as one viable alternative for individual transport. Bike-sharing systems (BSS), in which bikes are shared by users over short distances, are being introduced as one element of a new sustainable-mobility paradigm.

They offer a host of benefits including reduced congestion and fuel emissions, transport flexibility, health benefits, and financial savings for individuals. Such systems are widely considered to be one of the most promising sustainable urban planning interventions, and such schemes are now present in more than 1000 cities worldwide.

Locked-in barriers to bike-sharing

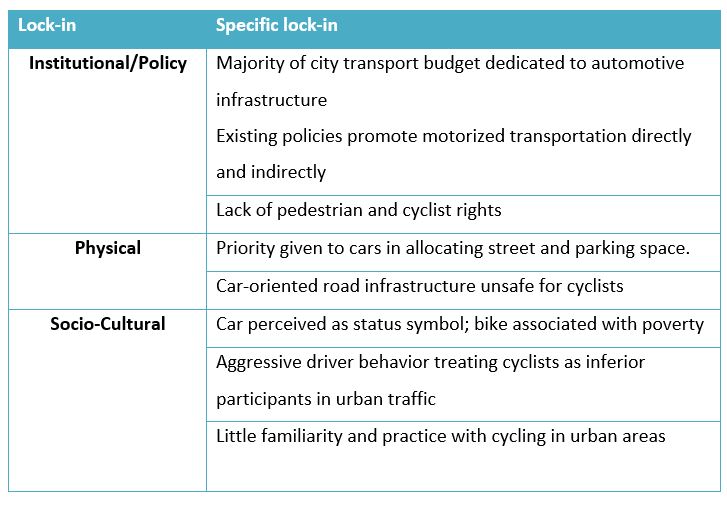

Despite this recent interest, BSS face a host of barriers, which can categorised as institutional, physical, and socio-cultural lock-in mechanisms that tend to maintain the status quo. These lock-ins help explain why progressive interventions such as BSS are often delayed or prevented, particularly in developing country mega-cities.

Mexico City is an exemplary case of a mega-city where car-centric lock-in mechanisms have long worked against change in the mobility system (see table 1, below).

Socio-cultural lock-ins in particular are often forgotten. Yet, they are usually the most difficult to overcome due to their association with individual beliefs and attitudes.

In many places the bike has long been considered the “poor man’s” mode of transportation, whereas the car is seen as a symbol of success. In Mexico, for instance, the term “pueblo bicicletero” (biking village) denotes a poor village, with the cyclist seen as someone poor and unable to afford a car. Such social perceptions have a strong cultural lock-in effect.

This lowly perception of the bike is reinforced by the mindset of many car drivers, who believe they have priority in the city landscape. Cycle paths and parking spots can be seen as detrimental to availability of space for cars, sometimes leading to aggressive behaviour by ‘entitled’ drivers. Such behaviours reinforce drivers’ domination in Mexico City and beyond by scaring off potential bike users.

Overcoming anti-bike-sharing lock-ins

In order to address these barriers, Mexico City came up with a comprehensive and creative set of measures.

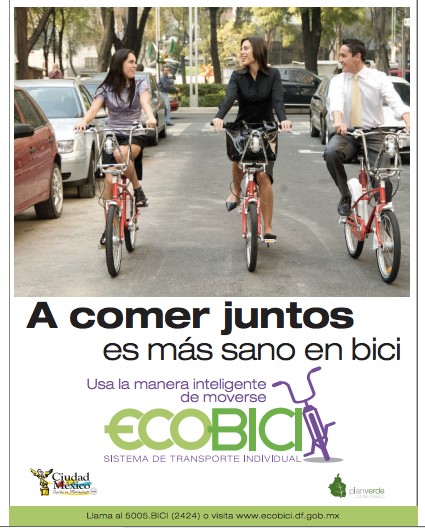

First, the city decided to change the image of the bicycle by branding the scheme as “the intelligent way to travel”: it’s healthy, helps the planet, and reduces travel time. This helped engender a new idea of cyclists: middle class, educated, and cycling out of choice rather than economic necessity. The bicycle has thus gained visibility, social acceptance, and legitimacy.

Second, the city decided to address aggressive driver behaviour through a campaign to educate drivers on the benefits of bicycles. Messages included, for instance, “One cyclist is one less car on the road for you to arrive to work faster” and “One cyclist is one more parking spot open to you.”

Another distinguishing feature of EcoBici is the use of yearly perception surveys with questions on user profile, travel characteristics, transport habits, and the impact of Ecobici on the user’s life.

The viability of EcoBici and the overall image of cycling has been transformed.

The programme, which started in 2010 with 85 docking stations and 1000 bicycles, has expanded to over 446 docking stations and 6000 bicycles. Demand averages 34,000 daily users. EcoBici is the largest in the region and has been replicated in other Latin American cities, as well as winning the 2013 Ciclociudades (Cyclecities) Award.

Ecobici has:

- reduced 8% of taxi use and 5% of private car use

- reduced carbon emissions by 499 tons of CO2

- saved more than 2,000 days in aggregated travel time

In addition, 82% of users have reported positive changes in their quality of life:

- 44% are more relaxed

- 38% save money

- 36% have improved physical condition

- 26% have more time

Taking bike-sharing to the world

Mexico is not the first and certainly won’t be the last city to move toward sustainable mobility.

As urban populations grow, traffic worsens, pollution soars, and a awareness of climate change rises, it is increasingly necessary to understand how best to promote successful transitions away from private motorised vehicles and towards more environmentally sound, efficient, and shared options.

Mexico City’s EcoBici bike-sharing programme shows specific ways in which the lock-ins of a motorised automobile system can be intentionally and holistically addressed. The successes of EcoBici could inspire other cities to believe that a transition towards BSS is possible, including in emerging-economy mega-cities.

A major opportunity is the fact that 60% of the urban areas needed by the end of this century still remain to be built, meaning that mobility systems for those cities are still in their formative stages. The overwhelming majority of these urban areas will be in developing countries. As such, efforts towards more sustainable urban mobility are both timely and necessary to avoid the long-term lock-in of highly polluting auto-mobility systems.

As one of the mayors of Lyon, France, famously said:

There are two types of mayors in the world: those who have bike-sharing and those who want bike-sharing.

In the 21st century, two hundred years after the invention of the bicycle, we may finally see a world with an overwhelming majority of the former.

Those cities will be less congested and polluted, will operate according to sharing principles, and will be more liveable and breathable. This is because they may at last be planned and built not for auto-mobility but for citizen mobility.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This is a slightly edited version of a post first published by LSE’s International Development blog

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting