City Bank’s history in Haiti shows how racial ideology and economic policy have long coalesced to justify colonisation in Latin America and the Caribbean, writes Peter James Hudson (University of California, Los Angeles).

City Bank’s history in Haiti shows how racial ideology and economic policy have long coalesced to justify colonisation in Latin America and the Caribbean, writes Peter James Hudson (University of California, Los Angeles).

Donald Trump’s recent description of Haiti, El Salvador, and Africa as “shithole countries [sic]” offered an ugly example of how US foreign policy is often shaped by the dictates of racial capitalism – by an economic system suffused with racial ideology and racist thinking.

The comment recalls an earlier episode of racial capitalism in Haiti which is depicted in my book Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean. On that occasion, however, the comments came from Wall Street rather than Washington, as part of the National City Bank of New York’s efforts to secure control of Haiti’s finances and banking.

The history of Citigroup in Haiti

Founded in 1812, City Bank is the predecessor of the contemporary multinational investment-banking and financial-services corporation Citigroup Inc. By the beginning of the twentieth century, its managers were seeking to transform it from a successful domestic commercial bank into an international financial institution that could compete with the dominant European banking houses.

Haiti was one of the earliest targets for City Bank’s internationalisation. This was part of a wider push into Latin America and the Caribbean that found support in the State Department. The US was then pursuing a policy of “dollar diplomacy”, attempting to use financial muscle to bring political stability to the region. City Bank’s initial investments in Haiti came through their participation in the financing of dock and railway projects in 1910. They used these initial investments as a springboard to take over control of Haiti’s economy and financial system, especially through the Banque Nationale d’Haiti, a privately run bank of issue controlled by French and German interests.

As City Bank’s investments in Haiti and the Banque Nationale increased, so too did their involvement in Haiti’s internal affairs. City Bank managers became critical liaisons for the State Department regarding Haiti’s politics during a period when the country was roiled by internal factionalism and disruptive pressure from French, German, and US political and business interests.

City Bank managers Roger L. Farnham and John H. Allen were critical in this regard. At one point, Allen was called to a meeting at the State Department by William Jennings Bryan and asked to explain Haiti’s history and current political climate. Allen described a country whose citizens were the descendants of formerly-enslaved Africans but whose culture was heavily influence by France. “Dear me, think of it!”, Bryan allegedly exclaimed in response, “Niggers speaking French!”

Registers of racial disdain

Bryan’s comments were not unusual. Not only did they reflect the sentiments about Haiti held by most Americans at the time, they also spoke to particular registers of disdain for the country within City Bank itself. Indeed, for Allen, Farnham, and other City Bankers the population of Haiti, like that of much of the Caribbean and Central America, constituted an inferior race whose biological impediments were compounded by the climate-induced degeneracy and torpor of the tropics.

In his dispatches from Haiti, Allen oscillated between describing Haitian people as unbridled savages and innocent but ignorant children. As he once wrote in the City Bank journal The Americas:

Haiti’s dark millions can be a menace to the United States, but under wise and thoughtful guidance can be developed into a self-respecting and dignified nation that could perhaps help in the solution of one of the greatest problems before us today, the future of the colored race.

Haiti, according to Allen, was “truly a virgin territory ready for the white man’s guiding mind to help it to get back to the conditions existing when, as history tells us, Haiti was the richest of all the colonies of France.” Farnham described the Haitian masses as “nothing but grown-up children.” Like Allen, he believed that Haiti’s regeneration could occur through the paternalistic tutelage of the US, that black self-government could only occur through white intervention. The Haitian people, Farnham stated, “must be taught.”

For City Bank in Haiti, racial designations guided financial considerations and economic policy was embedded in racist ideology. Such considerations, and the belief in the power of “the white man’s guiding mind,” undergirded a memorandum on Haiti that Farnham wrote for Secretary Bryan in 1914. Known as the “Farnham Plan” it argued that Haiti’s internal political conflicts could only be settled by the takeover of the country by a stronger nation and that such a takeover would be welcomed by the majority of the Haitian people given that they were used to strong-men in power.

The coalescence of US economic and political interests

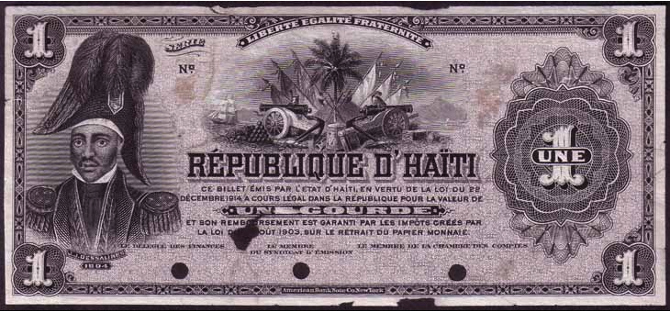

While the Farnham plan was a call for US military intervention based on racial paternalism, it was also a means through which the US military could be used to protect City Bank’s financial and commercial interests in Haiti. City Bank worked to make intervention inevitable. They used the Banque Nationale to manipulate the price of the gourde, Haiti’s national currency, withheld public salaries, and starved the government of its operating budget.

In 1914, in what was seen as a deliberate challenge to Haiti’s sovereignty, the bank ordered the transfer of Haiti’s gold reserve from the vaults of the Banque Nationale to Wall Street aboard a US gunship. By 1915, Haiti’s sovereignty was extinguished entirely when the Farnham Plan was effectively enacted with the landing of US Marines, an action justified in terms of Haiti’s internal political turmoil, the supposed threat of Germany in the Caribbean, and a desire to protect US interests.

The US military occupation of Haiti acted as a guarantee on the City Bank’s investments in the country. By 1922, French and German interests in the Banque Nationale were eliminated and it came under the total control of City Bank. Customs collection was regularised, ensuring bond payments on the bank’s railroad and dock projects, while the political risk to investors on the bank’s $30 million loan to the country was eliminated. Farnham, in particular, benefited from the occupation, receiving a substantial payout and annual salary as the receiver of one of Haiti’s railroads.

While one City Banker described Haiti as “a small but profitable piece of business”, such profits came at great cost to the Haitian people. Their business was written in a ledger of violence: in the brutal suppression of a series of peasant insurgencies that left dozens of villages burned, thousands of Haitians dead, and hundreds more jailed or forced to work on chain-gangs that recalled the days of slavery.

The occupation lasted nineteen years (until 1934) and only ended because of a country-wide protest movement and adverse publicity for City Bank in the US. While the Marines were withdrawn in 1934, the Banque Nationale remained under the direct control of City Bank until 1941, when it was sold to the Haitian government for $500,000. Yet even after 1941, Banque Nationale continued to be managed by City Bank appointees, and City Bank continued to act as its international correspondent bank.

Racial ideology and economic policy in Haiti and beyond

City Bank’s history in Haiti shows how imbrication of racial ideology and economic policy can occur. It also suggests that finance capital is embedded in cultural and racial discourse – that banking and investment are constituent parts of racial capitalism.

This is not limited to Haiti. Such questions shaped City Bank’s engagements in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Panama – but also in “white” countries like Argentina. Nor was it limited to City Bank. Similar considerations were at work in Chase Manhattan’s engagements with Cuba and Panama and those of Brown Brothers in Nicaragua. Indeed, Nicaragua was described as the “Republic of Brown Brothers” in the 1920s due to its degree of control, with the manager of one of its subsidiaries there, W. Bundy Cole, commenting, “I do not think any Indian or any negro is capable of self-government.”

Trump’s “shithole countries” comment continues this long tradition of entangling racial denigration and economic policy. It came in the midst of an ongoing and contentious national debate over citizenship, economics, race, and immigration, and it was followed soon after by an announcement barring Haitian citizens from visas for agricultural labourers and temporary workers.

But if Citigroup’s recent takeover of Puerto Rican debt and public utilities in the wake of Hurricane Maria is any indication, investing in shithole countries remains just as lucrative for Wall Street as it has been for centuries.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This post draws on the author’s monograph Bankers and Empire: How Wall Street Colonized the Caribbean (University of Chicago Press, 2017)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

good read, Thank you GUY

Fast forward to 2020 and what do we have now? Haiti is directly in our backyard and we have ignored the worst failed state in our hemisphere for years. However, this has not escaped the attention of the now highly ambitious Chinese who, as we speak, are providing aid to both Haiti and Jamaica. You leave the door open, you ignore the plight of the poorest and bad things will happen!

The Chinese, it is reported, follow a strategy of the “debt trap”. They loan far more than a country can ever repay and when the country defaults on the loan, they take a port, an airport, etc as payment. Eventually, some of these “payments” turn into military bases! And, this is going on all over the world right now. In my opinion, what a disaster for the US.