The Peace Community of San José de Apartadó shows that victims of armed conflict are also producers and creators whose knowledge could contribute to a future-oriented understanding of peace-building that would benefit all Colombians, writes Gwen Burnyeat (University College London).

The Peace Community of San José de Apartadó shows that victims of armed conflict are also producers and creators whose knowledge could contribute to a future-oriented understanding of peace-building that would benefit all Colombians, writes Gwen Burnyeat (University College London).

• Disponible también en español

The first eighteen months of the implementation of Colombia’s peace accords have been disappointing.

The demobilisation of FARC was an important achievement, but a litany of assassinations of social and community leaders, as well as of demobilised FARC members and their families, allows us to see into the dark crystal ball of Colombia’s possible future: a post-conflict much like that of El Salvador, where old violence is simply recycled and rebranded.

Everyone knew that when the FARC withdrew from areas that they had controlled, power vacuums would be left. The government’s promise, at least discursively, in the Havana Accords, was that these would be filled by the presence of state institutions – both military and civilian. But this has not happened, and instead the vacuums are being filled by paramilitaries, the ELN guerrilla, and criminal gangs.

Despite the fact that everyone knew this would happen, there did not seem to be any kind of contingency plan, perhaps because of the government’s diminished political leverage after the failed peace referendum.

In August 2018, Colombia will have a new president. If Gustavo Petro wins in the second round of the presidential elections on 17 June 2018, there will continuity of the Santos administration’s policy on the peace process. But if Iván Duque prevails, the peace process could be substantially deconstructed, with a return to a hard-line military stance. It is not an exaggeration to say that the country’s future hangs in the balance.

But it is also important to remember that peace does not depend on a top-down negotiated solution, important though this may be. In reality, it depends on society.

Thus far, Colombian society has proven a poor ally in the search for an end to the armed conflict: after four years of negotiations, 50.2% of voters rejected the peace deal, 63% abstained from voting, and swathes of society viewed the peace process with inertia, suspicion, and cynicism rather than as a historic opportunity. These are the inevitable effects of a society polarised and paralysed by 50 years of war.

But it is Colombian civil society which holds the key to peace, not only through voting behaviour, but also through the possibility of defining and shaping what “peace” could mean.

Not only victims and defenders, but also producers and creators

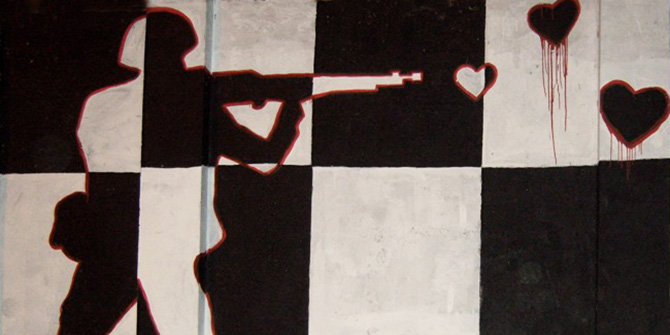

In my recent book Chocolate, Politics and Peace-Building, I tell the story of the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó in the north-western conflict zone of Urabá. Trapped between left-wing guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries, and the Colombian army, this community famously declared itself neutral to the armed conflict as a self-protection strategy.

Despite massacres, multiple forced displacements, torture, death threats, forced disappearances, and selective assassinations of leaders and even children, they have stubbornly and staunchly remained on their land, even though it occupies one of the most geostrategic and resource-rich corners of Colombia, making it lethally attractive to agri-business and drug-mafia clans.

The Peace Community is internationally renowned for its pioneering position of neutrality and its determination to denounce human rights violations by all sides. In my book, however, I tell their story through a different lens: one of organic productivity.

The people of San José de Apartadó have been producing cacao since long before they became a “peace community” in 1997. Today, they export 50 tons a year to British multinational Lush Cosmetics, who use the cacao butter in a “peace” massage bar sold at 1000 shops in 50 countries, helping to raise awareness about the Peace Community’s human rights situation.

It is in the heart of the Community’s organic cacao groves and the surrounding forests of the Abibe mountain range that a profound knowledge of “peace” is found, not in the grey corridors of power in Bogotá.

As I argue in my book, the people of the Peace Community are not simply defenders of life, calling for an end to the violence that affects those millions of rural civilians trapped between conflict actors. They are also producers of chocolate, Colombia’s national breakfast drink, and creators of their own conception of peace.

This conception goes beyond the absence of violence, speaking to principles of solidarity, community labour and economics, relationships with nature, social justice, and keeping historical memory alive. Ultimately, these are principles which could offer hope and inspiration to all Colombians at a time when they are deeply engaged in a long-term national debate about what “peace” might mean.

This requires looking back to the past of the country’s internal conflict to begin to understand the atrocities that rural victims lived through and therefore also the need to put an end to enduring cycles of violence. But beyond this, it also means understanding that people like those in the Peace Community are not just “victims” but also human beings with knowledge that could contribute to imagining peace-building in a future-oriented sense, to the benefit of all Colombians.

The people of the Peace Community have arrived at their profound conception of what “peace” means though reflecting on the multi-dimensional forms of violence that they have lived, felt, and perceived: direct assassinations, the structural violence of poverty, the cultural violence of stigmatisation, and persistent efforts to undermine their struggles for justice.

In the midst of war, they created life. In the words of one member:

Trailer for the ethnographic documentary Chocolate of Peace (2016), produced and co-directed by the authorWe strive for something alternative. As we say, a life path which builds peace. In the Community, it is our life for our brother. Where there is death, we sow life.

Learning from the Peace Community

In Colombia as elsewhere in the world, it is often in the darkest corners, where people have suffered unimaginable atrocities, that the greatest expressions of humanity and creativity can be found.

The Peace Community’s reflections on “peace” could be relevant even at a global scale in our increasingly uncertain world. Their experiences invite us to rethink our relationship with food; to value the efforts of those who produce it, their knowledge, struggles, and ideas; and to build bridges between victims of all types of violence and global civil society. Turning to the lessons, experiences, and knowledge of collective leadership processes will be crucial for the next phase of the post-conflict in Colombia, whether the next president is pro-peace or pro-war.

Thousands of organisations, communities and networks have spent the last six years, since the negotiations with the FARC began in Havana, investing energy, painstaking effort, and above all love in supporting the national peace policy from the bottom up. This is not to say that they necessarily support the government, rather that they recognise that peace is beyond politics and should belong to society. The Peace Community of San José de Apartadó is but one example.

The best Colombians could do right now would be to turn to such vibrant collective leadership processes for inspiration. In the current context, organisations like the Peace Community are under increased risk, with assassination attempts having recently been carried out on their leaders.

The rest of Colombian society needs not only to stand in solidarity and condemn the attacks against them, but also to seek out the knowledge and praxis of those who have suffered most from armed conflict yet managed to cultivate life and hope amidst death and destruction.

These are the unsung heroes of Colombia.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• This article draws on the author’s book Chocolate, Politics and Peace-Building: An Ethnography of the Peace Community of San José de Apartadó, Colombia (Palgrave Macmillan 2018)

• Images are not covered by the text’s Creative Commons licence (© 2018 Gwen Burnyeat)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting