Local residents unhappy with the established “safari” model of favela tourism are creating a novel and vibrant market for walking tours in neighbourhoods like Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro. Social media have allowed them to reach potential customers directly, whereas temporary local alliances mean they can provide a “product” that is both safe and seductive at the same time. Aside from boosting the local economy, this allows visitors to experience the favela as a welcoming and thriving community rather than the dangerous drug den depicted in mainstream media, writes Josiane Fernandes (University of Lancaster).

Local residents unhappy with the established “safari” model of favela tourism are creating a novel and vibrant market for walking tours in neighbourhoods like Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro. Social media have allowed them to reach potential customers directly, whereas temporary local alliances mean they can provide a “product” that is both safe and seductive at the same time. Aside from boosting the local economy, this allows visitors to experience the favela as a welcoming and thriving community rather than the dangerous drug den depicted in mainstream media, writes Josiane Fernandes (University of Lancaster).

• Também disponível em português

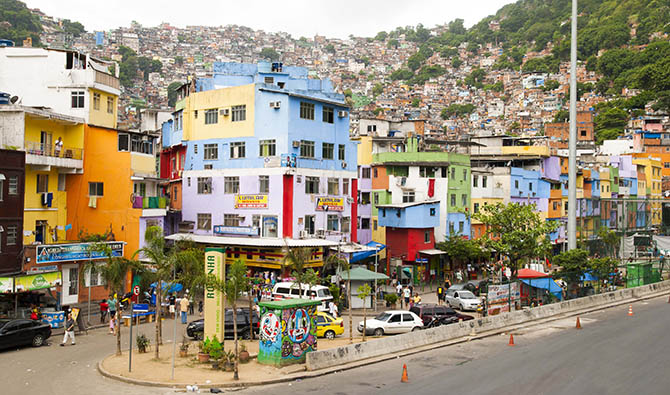

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you read “favelas in Rio de Janeiro”? For most people the answer would probably involve issues like poverty, crime, guns, and drugs that are commonly associated with the stigmatised version of the favela. But as enterprising residents begin to establish a homegrown market for tourism in these often notorious neighbourhoods, that could be changing, and the key to their success is a combination of social media and temporality.

Tourism in the favela

Rio, a hugely popular tourist destination, is well-known for the stark contrast between its stunning vistas and its rampant inequality. Multi-million dollar apartment buildings with ocean views loom decadently over the favela neighbourhoods that huddle at their feet. Despite attempts to hide the favelas from tourists, they remain an obvious part of the landscape, yet they have tended to be overlooked by the streams of tourists heading for local beaches like Ipanema and Copacabana.

That said, favela tourism is not a new phenomenon. Agencies from outside the favela started offering this kind of “reality tourism” in the early 1990s, particularly after the 1992 Conference on Environment and Sustainable Development in Rio de Janeiro. Favela residents, however, reaped little reward when outside businesses brought hordes of curious outsiders into their living spaces. There were two related issues:

- Tourists arrived in “safari mode”, circulating in jeeps while snapping pictures with expensive cameras.

- Outsiders remained completely detached from the community, and residents were rendered passive spectator-attractions.

Unhappy with this situation, a few locals in Rocinha – the largest favela in Rio – decided to start their own tours offering a very different experience. These entrepreneurial locals adopted a walking-tour format, where visitors would engage with people in the community, have meals in local restaurants, and visit artists’ workshops and social projects. This way, tourism would serve a double purpose: boosting the local economy and providing visitors with a chance to see the favela as a welcoming, thriving community rather than a dangerous drug den.

But these pioneers first needed to clear one obvious hurdle: how do you attract tourists into the favela in the first place?

Different media, different effects

Perhaps the first notable media production that depicted favelas in any real detail was the hit movie City of God. Released in the early 2000s, it depicted a favela dominated by drug gangs, with extreme violence used to exert control over poor communities. Despite the development of digital technologies that can offer new insights into the realities of favela life, this image of criminals and violence endures, and it continues to impact directly on how favelas and their residents are perceived by foreigners and Brazilians alike.

But favela entrepreneurs recognised that social media also offered a means of fighting social stigma by reaching out to target audiences directly. All across Rio, these entrepreneurs are using Facebook to promote tours and to share reviews by previous visitors. On their business pages, anyone can access photos, videos, and testimonials from tourists from all over the world, most of whom recount positive experiences in the favela. Social media thus enable tourists first to enter the favela virtually, transforming something feared and unknown into something familiar.

More importantly, social media allow favela entrepreneurs to show that shootings and gangs are not omnipresent, albeit without denying their all-too-real existence. In fact, the idea that gangs and armed conflict coexist in the very same areas is part of the seductive balance between safety and danger that makes favela tours attractive. Our research shows that social media allow favela entrepreneurs to turn aspects of their stigmatisation to their own advantage by using them to create a compelling market offer.

Temporary alliances for security and saleability

When booking a tour in Rocinha, potential visitors receive a set of specific instructions. They are told they will be picked up at the bottom of the hill, usually by the Sao Conrado/Rocinha metro station, at a certain time, and by a certain person. They will be taken along the main street in Rocinha and then up the hill, visit local shops and restaurants on the way, and talking to local residents.

They might see a capoeira show and go to a laje – a rooftop typical of favela housing – to enjoy a traditional Brazilian feijoada stew, all the time being made aware of where heavily armed gang members are stationed. In fact, some favela entrepreneurs even offer to include gang areas in their tours as long as certain rules – particularly as regards photography – are followed, and this makes “the product” even more enticing.

The key to this provocative but credible approach is temporality. Favela entrepreneurs offer the promise of a temporary alignment of people and services that can provide a safe tourist experience within established bounds. The market offer is that at a certain time, in certain places, guided by certain people, Rocinha can be tourist site just as safe as any other area of Rio.

“A lot of people have prejudices, they’re afraid. So when we show them that they can come, that we have a group of locals that have a local tourist agency, that they can come safely, they can see that it has entertainment, […] they will see the problems, but they will also see what’s new, because Rocinha has its glamour.” (A., Rocinha resident and tour guide)

The beauty of social media is that it brings this promise to life. On Facebook, potential visitors who might never have set foot in Brazil can visualise and engage with the favela. They can use other digital platforms and websites like TripAdvisor, Google Maps, and Yelp! to check other reviews or even to explore the streets of Rocinha. For favela entrepreneurs, meanwhile, social media provide a way of conveying their own narrative and counteracting stigmatisation of the favela in the mainstream media.

Overall, our research shows that social media can play a vital role in creating and maintaining the favela tourism market. Their particular strength is that they can connect distant people and places, making something long inaccessible feel suddenly accessible.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors and do not reflect the position of the Centre or of the LSE

• Please note that not all images are covered by the site’s overall Creative Commons licence

• This post draws on the contributor’s co-authored article Managing to make market agencements: the temporally bound elements of stigma in favelas (Journal of Business Research, 2019)

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting