The recent shooting at the Cielo Vista Walmart in El Paso has been depicted as a tragedy for local people, reigniting well-practiced debates about gun control, video games, mental health, and “lone wolf” extremism. But this framing not only underplays the impacts on connected communities like Ciudad Juárez across the border, it also fails to acknowledge this massacre’s place in a continuum of race-based and structural violence that has long shaped the experiences of the people of the US-Mexico border, writes Gabriella Sánchez (European University Institute).

Last Saturday, a young man carrying an assault rifle burst into a Walmart Store in the US-Mexico border city of El Paso, Texas, and proceeded to kill 22 people and wound an estimated 26 more. The events have since been repeatedly characterised as unimaginable in a city like El Paso, which has for years been proud to call itself one of the safest in the United States.

Journalistic coverage of the event immediately hit social media, relying on a now common formula. Viewers from around the world have been treated to hour upon hour of rolling coverage and debate on gun control, the role of video games in fostering violence among disenfranchised American youth, and possible mental health issues that the suspect may have had.

Also predictable has been the parade of terrorism experts discussing at length the nature of “lone wolf” extremists and white supremacists in a way that uncritically positions such people as isolated, marginalised, and misunderstood white males.

Events in El Paso have also been described as the largest racist attack on Hispanics in the history of the United States. The suspect is believed to have posted a manifesto online a few minutes before the shooting in which he outlined his dislike for Hispanics, whose presence in the state of Texas he characterised as “an invasion”.

Creating an El Paso outside of politics, history, and border society

From the outset, the events of last Saturday were portrayed as a tragedy for the city of El Paso, with local people depicted as inherently compassionate, religious, and warm. Images of elderly women holding each other in consolation, large crowds gathering to pray, and memorials overflowing with flowers, teddy bears, and both Mexican and American flags have been commonplace in social media feeds, along with taglines that emphasise the city’s tight-knit sense of community.

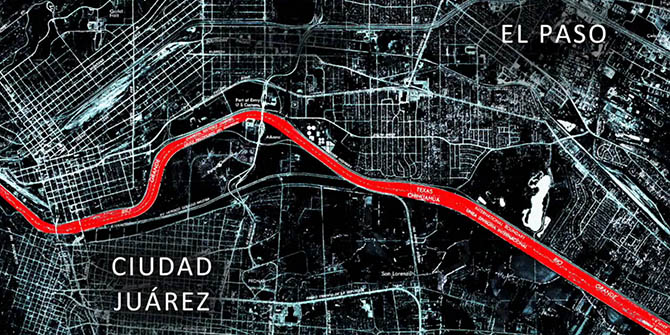

Yet, the massacre has also been systematically portrayed as affecting El Paso alone, which in turn disregards the impacts on the people of Ciudad Juárez – El Paso’s conjoined neighbour on the Mexican side of the border – and of the many rural and indigenous communities on both sides of the divide.

This emphasis on El Paso has virtually obliterated the historical, political, and community dynamics that have long existed amongst the peoples inhabiting both sides of the wider US-Mexico borderlands. And more importantly, it has obscured the shooting’s place in a broader continuum of race-based and systemic violence against people of colour in the region, a process that has gone on for generations. The effect is to create a more palatable, digestible version of the US-Mexico borderlands.

This is not to suggest for one second that El Paso is unfriendly or its people unkind. A visit to Walmart in El Paso on a Saturday morning does indeed provide deep insights into life on the US-Mexico border. Grocery shopping is a family affair: it is not uncommon to find entire families descending from cars to load up on the household basics. Nor is it unlikely that you will see neighbours, friends, and relatives greeting each other effusively in the aisles – be it in English, Spanish, or both – and casually saving spots for each other at the checkouts despite the protests of the rest of the line.

A cross-border tragedy

The Walmart Store in question, at Cielo Vista Mall, is indeed a preferred destination for these kinds of families, but it is also located just minutes from the international bridge connecting El Paso and Ciudad Juárez, and the surrounding area has an even higher concentration of Mexican and Mexican-American families than the rest of El Paso. There are plenty, too, who cross the border from Ciudad Juárez on weekends to take advantage of Walmart’s low prices. With back-to-school season in full swing, last weekend was no exception. It is estimated that between 1,000 and 3,000 people were inside the store at the time of the shooting.

But the people impacted by Saturday’s events were not only El Pasoans. As of Tuesday 6 August, at least eight – that is, a third – of the confirmed dead were Mexican citizens who had crossed into El Paso to buy their groceries. It is also believed that many others may have fled the scene despite being in need of medical attention for fear that the authorities might judge them to be foreign or irregular on the basis of their appearance. Such are the effects of the extreme anti-immigrant climate whipped up by the Trump administration.

While the shooting has been portrayed as a wound in the collective consciousness of El Paso alone, it has impacted the lives of men, women and children from communities on both sides of the border, and it must therefore be understood and framed binationally.

Beyond “being nice”, sharing shopping venues, and enjoying similar food or music as the mainstream media have condescendingly emphasised, people of colour along the US-Mexico border also share a long history of race-based discrimination and state-sponsored violence.

Contrary to the narrative of the Cielo Vista Walmart shooting as unprecedented or unfathomable, the shooting and its depiction are just one more example of race-based violence against people of colour on the US-Mexico border. This type of depiction also attests to how people’s experiences as othered bodies have historically and systematically been retold, simplified, or silenced in favour of a more palatable narrative of otherness and space (in this case, the border). Acts of violence against people of colour from the borderlands are anything but new or unusual.

Race and violence at the border

The historical record on the racially animated abuse at US border is long and deeply unpleasant: from the expulsion of Chinese men in the 1800s to restrictions on the mobility of binational Native American tribes; from the mass deportations of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the 1930s and discrimination against Bracero temporary workers to the ongoing deaths of people seeking to enter the United States from Mexico.

But perhaps the most current issue – yet not quite present in debates about the El Paso shooting – is the way in which the El Paso-Ciudad Juárez corridor has, since 2018, been the epicentre of the humanitarian response to the US and Mexican decision to try to reduce asylum applications at the border by resort to mass detention, family separations, and returns.

While the harrowing experiences of those seeking asylum at the US-Mexico border have been covered to an almost voyeuristic degree, the media, policymakers, and scholars alike have failed to articulate a critical posture that places the El Paso shooting and racialised migration-control measures at the border on the same continuum.

The opportunity to connect the shooting to migration policy was not wasted by the White House, however, with Donald Trump tweeting by Monday morning to suggest that combined gun-control legislation and immigration reform could reduce the likelihood of a repeat of such events. Even now, as the evidence points towards hate crime as a possible explanation, few have examined the linkages between the two main angles that have dominated the discourse around the El Paso shooting: one framing the shooting as a terrorist act and another emphasising its nature as a hate crime. Both must be throroughly unpacked, for separately they provide only a skewed, partial, and decontextualised narrative of Saturday’s events.

The El Paso shooting in context

Overall, the El Paso shooting can only be understood through a binational, intersectional, and historical lens that frames it as part of a continuum of race-based and structural violence that has long shaped the experiences of the people of the border. The shooting’s repercussions will not be felt in El Paso alone. They will live long in the memory of the people of colour on both sides of the border as another example of the hate and discrimination that they have faced for generations.

For that reason alone, any claim about the El Paso shooting which does not make reference to the way race and racism have been constants in the lives of the people of the US-Mexico borderlands is in itself a further act of violence, for the more palatable depiction simply permits continuation of an already long history of structural violence perpetuated by the state.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting