Freedom of information requests have allowed researchers and activists in Mexico to gain access to official data on clandestine mass graves. But this process also revealed major discrepancies between datasets covering the same periods but provided at different times and to different institutions. Uncertainty around such crucial numbers not only undermines political demands for accountability amidst Mexico’s crisis of violence, it also obscures the atrocity and the disappeared individual behind every missing number. Only the creation of transparent, integrated records can resist and reverse this double disappearance of the thousands of victims lying in Mexico’s mass graves, writes Carlos Dorantes (ARTICLE 19).

Freedom of information requests have allowed researchers and activists in Mexico to gain access to official data on clandestine mass graves. But this process also revealed major discrepancies between datasets covering the same periods but provided at different times and to different institutions. Uncertainty around such crucial numbers not only undermines political demands for accountability amidst Mexico’s crisis of violence, it also obscures the atrocity and the disappeared individual behind every missing number. Only the creation of transparent, integrated records can resist and reverse this double disappearance of the thousands of victims lying in Mexico’s mass graves, writes Carlos Dorantes (ARTICLE 19).

The absence of public and integrated national records of clandestine mass graves in Mexico allows for the manipulation of databases and hinders calls for accountability. The resulting uncertainty has profound effects in terms of social control, allowing security institutions to manage victims’ demands.

Obly by litigating for access has it been possible to understand these practices and gradually reconstruct the bigger picture from various fragments of information. The grim conclusion is that 1,606 clandestine graves and 2,489 bodies have been found so far in Mexico, according to official records.

Mexico’s crisis of violence

But those found are only a fraction of those disappeared. Mexico is facing a humanitarian crisis that official sources say has taken the lives of 252,000 people (2006-2017). The use of disappearance has become widespread amongst the various groups engaged in violence, with clear links also between gross human rights violations, organised crime, and government officials at every level.

Federal authorities acknowledge at least 38,000 disappeared persons (as of April 2018). However, counts from unofficial records indicate around 46,000 disappearances over the same period. The country is reminded of the depth of this crisis every Mothers’ Day (10 May), when thousands of relatives and mothers of the disappeared from all over Mexico gather in the capital to put pressure on authorities via the National March for Dignity.

In their desperation, some of these relatives have even decided to go out into the field themselves to search of the graves of their loved-ones, sometimes covering wide expanses of land with little or no state protection.

As María Herrera – mother to four disappeared sons – has said on the implementation of effective search strategies by National Search Commissioner Karla Quintana, “we can’t wait for the state any longer; the pain gets worse with every passing day”.

Piecing together the puzzle through information requests

In this context, the NGOs ARTICLE 19 and the Mexican Commission for Promotion and Defence of Human Rights (CMDPDH), along with the Iberoamerican University, lodged a request for information on mass graves with the offices of the attorneys general of the 32 states and the Attorney General’s Office (PGR) at the federal level.

ARTICLE 19 then embarked on a four-year struggle (2015-2018) with the PGR over access to information on clandestine graves, which ultimately revealed significant discrepancies on data within the institution.

In March 2015, ARTICLE 19 requested from the PGR (Infomex 0001700095215) statistics on:

- Clandestine graves found between 1960 and February 2015

- Bodies found

- Bodies or remains identified

- Sex and age ranges

- Signs of torture

- Investigations carried out

- Persons convicted (and the nature of their crimes)

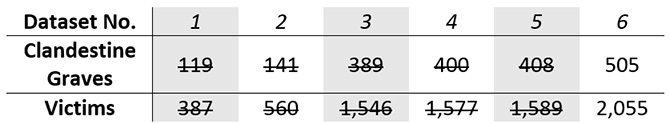

Over the course of the litigation process, ARTICLE 19 received six separate sets of information. As appeal followed appeal, however, the data provided began to change significantly. First, the data showed 119 clandestine graves with 387 bodies. Then the figures changed to 141 graves and 560 bodies. As the table below shows, the degree of variation shot up across subsequent reports:

In total, the Attorney General’s Office (PGR) acknowledged 505 graves and at least 2,055 bodies from the year 2000 to February 2015, with no records forthcoming for the period 1960-2006. The PGR reported identification of just 126 bodies (only 6% of the total). By 2015, the agency had opened 81 investigations, for which it has convicted 106 people. The crimes prosecuted, however, were not related to deaths or irregular burials.

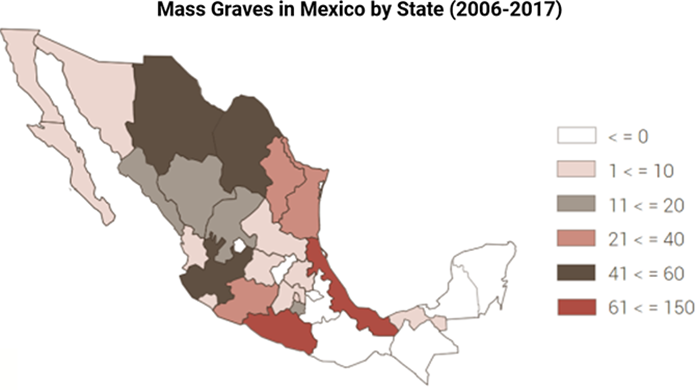

When this information was cross-referenced with data from the 32 local attorneys general offices, it was found that from 2006 to 2017, across 24 administrative zones, 1,606 graves were found and 2,489 bodies were exhumed. Of those, only 434 people have been identified (around 17%).

Understanding discrepancies in mass-grave and victim data

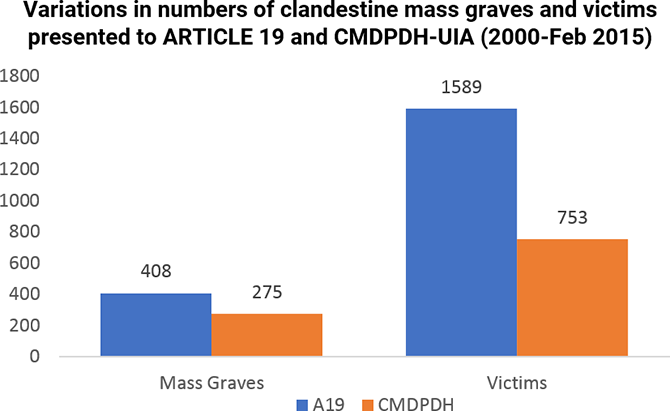

The federal judge in this case found that “the figures presented by the General Attorney Office fail to offer minimum certainty to the requester”. This in turn led our research team to compare data presented to us at ARTICLE 19 with the information given by the PGR to the Mexican Commission for Promotion and Defence of Human Rights (CMDPDH). As the chart below reveals, there were significant discrepancies.

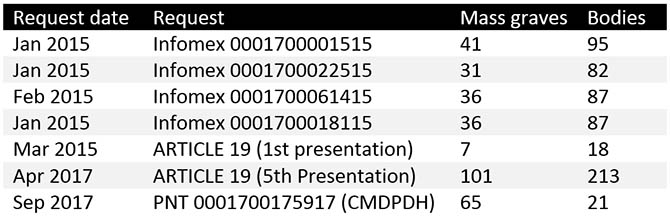

We then went on to compare the data we received with requests presented by other citizens for 2014, the year when 43 students from Ayotzinapa disappeared in Guerrero. The results were similarly varied:

As the table above shows, PGR provides different information to different applicants who make the same request. This situation demonstrates the urgent need for two key reforms:

- Creation of a National Registry of Clandestine Graves via a transparent methodology that allows for social participation; a national registry is foreseen in the General Law on Disappearance (2017) but has not yet been implemented

- Establishment of clear rules on organising archives within and between jurisdictions

These findings, however, also raise other serious questions about how such major discrepancies impact upon the real world and whether they arise by accident or by design.

Dead to the data: a double disappearance

This lack of consistency in the numbers has a political function of social control, albeit one that may derive from the daily practices of the state rather than planned policy. Attempts to access information show how security institutions work in contexts of widespread violence, with a tendency towards fuzzy record-keeping practices when it comes to “uncomfortable” issues such as human rights violations.

Similar mechanisms have been used in the past to create vague concepts, terminology, and statistics around atrocities. For instance, during the political violence committed against social movements from the 1960s to the 1980s, the records of Mexico’s National Security Directorate (DFS) used euphemisms – such as “package”, “detained”, or simply bare numbers – to document disappearances. Similar techniques were applied by other security institutions elsewhere in Latin America, as in the case of Guatemala’s National Police.

Missing people act as a reminder of impunity and the failure of the justice system in regimes both dictatorial and democratic. But while the disappeared serve to keep the past open, institutional opacity and uncertainty represent an attempt to close off the past and erase memory. In the end, these practices hinder victims’ claims and inhibit broader political pressure from civil society, as unclear records make it impossible to gauge the scale of the crisis and formulate appropriate demands for justice.

And, of course, these figures are not just statistics. Every missing number is also a real story, a disappeared person, and an atrocity. It is the lack of integrated databases like the proposed National Registry of Mass Graves in Mexico that allows these numbers, these stories, these disappearances, and these atrocities to be missed.

This is, then, a double disappearance: the physical disappearance of individual human beings is compounded by their second disappearance from official records, documents, statistics, and archives. Only through the creation of transparent, integrated records can their memory be restored and secured.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This text summarises findings of the report Violence and Terror. Findings on Mass Graves in Mexico (2006-2017), which was authored by Jorge Ruiz, Denise González, Lucía Chávez, Ana Ruelas, Carlos Dorantes, and José Guevara and presented at the VI Global Conference on Transparency Research, Rio de Janeiro, June 2019

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting