Policies and interventions designed to target “bad” youth involved in the extralegal activities of Colombia’s non-state armed groups are too simplistic to prove effective. The reality of youth involvement is complex and heterogenous, not least because it can be motivated by “good” intentions and obscured by “good” behaviours. Only a more holistic approach and a shift in paradigmatic thinking can recognise these realities and move towards more effective efforts to reduce youth participation, writes Erin K. McFee (University of Chicago) following on from her participation in the LSE LACC, PUC-SP, UNICAMP Researcher Links Workshop on Governance, Crime, and International Security.

Policies and interventions designed to target “bad” youth involved in the extralegal activities of Colombia’s non-state armed groups are too simplistic to prove effective. The reality of youth involvement is complex and heterogenous, not least because it can be motivated by “good” intentions and obscured by “good” behaviours. Only a more holistic approach and a shift in paradigmatic thinking can recognise these realities and move towards more effective efforts to reduce youth participation, writes Erin K. McFee (University of Chicago) following on from her participation in the LSE LACC, PUC-SP, UNICAMP Researcher Links Workshop on Governance, Crime, and International Security.

• Também disponível em português

On Christmas Eve 2015, I found myself in conversation with ten-year-old Dani in the informal housing settlement of Las Delicias, at the peri-urban edge of Florencia, Caquetá. Dani was a regular presence at the Reconciliation House, the NGO through which I conducted my fieldwork, and he was the youngest of three sons to a single mother who lived nearby. He consistently attended school and attained grades that demonstrated some degree of effort. His mother, Camila, was forcibly displaced by the guerrillas in 2002 and attended activities at the Reconciliation House as often as she could, frequently expressing anxiety about getting her sons into as many after-school sessions as possible in order to keep them off the streets.

That night, Dani’s small hand extended towards me holding a shot of aguardiente anise liquor as part of the holiday festivities. I looked at the liquor, then back at his ten-year-old face and sighed, no longer surprised, but still disheartened. I thanked him and took the shot, asking him what he was up to for the night. “I have to do a farra”, came the reply.

As Dani and other young people had explained them to me, “farras”, or parties, were gatherings of young people who liked to listen to music and dance. But a local police lieutenant who specialised in non-state armed groups (NSAGs) and recruitment prevention offered a different discourse: the neighbourhood microtrafficking networks used these parties to give away free drugs, get kids addicted, and grow the customer base. By telling me he was “doing” the party that night, Dani was letting me know he was on the distribution side of things.

“Why do you get mixed up in that shit?”, I asked him.

“To provide”, he responded. The proceeds of his drug dealing that evening would go to the household.

Youth participation in non-state armed groups

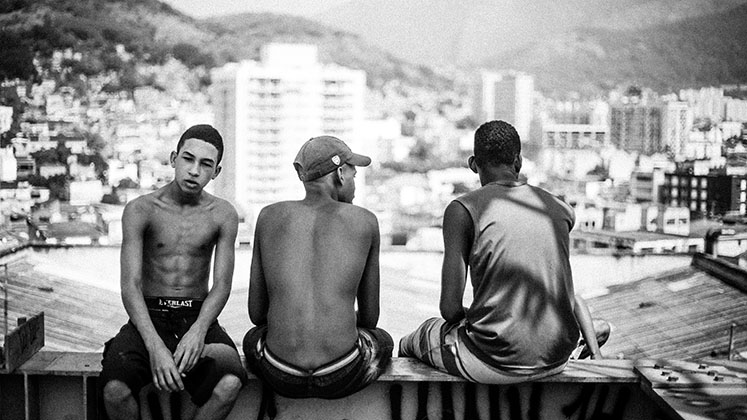

NSAGs represent one of the greatest policy challenges in contemporary Latin America and contribute directly to the region’s dubious distinction as the most violent in the world outside of “traditional” warfare contexts. Policy interventions to address NSAGs have met with limited success at best. Repressive approaches in particular have tended to exacerbate insecurity. In part, this is due to a failure to understand the nuances of the phenomenon.

Dani’s story is illustrative of a particular set of under-explored pathways into the activities that sustain NSAGs: his participation is not primarily motivated by power, status, or escape from a toxic home environment. He does not participate regularly as a “member” or “belong” to the group.

Organisational and policy interventions attempting to prevent youth participation in NSAGs would largely miss his case because they tend to overlook “good” sons and daughters who understand NSAGs as a viable, part-time alternative means of pursuing otherwise “good” ends (such as providing for the household or making money to continue in school).

When I refer here to “good” or “bad” youth, I am not making a moral judgement. Rather, I refer to the perspective of the intervening organisations and governmental institutions that screen for particular kinds of individual and familial profiles.

Although youth like Dani may be found in high-risk community settings, he and his family would otherwise elude detection in the design of policies and interventions because they do not exhibit the “bad” qualities targeted: for instance, violence in the home, truancy, drug use, or a desire for the kind of belonging and identity that NSAGs are believed to provide to disenfranchised youth.

In order to explore patterns of NSAG participation and exit, I conducted 15 months of ethnographic fieldwork in Las Delicias, followed by 20 months with the United Nations Agency for Migration’s Programme for Reintegration and Prevention (of recruitment) in Bogotá.

Like research carried out in Barrancabermeja by cultural psychologist María Cecilia Dedios, my fieldwork revealed a greater degree of porousness in gang membership than previously thought possible. And Dani’s story is just one illustration of this evolving nature of participation in NSAGs in Colombia: recruitment and utilisation patterns elude and subvert the tactics used to target “bad” kids, while new and variable forms of participation, entry, and exit emerge. There are clear and significant implications for public policy and intervention design.

Evolving patterns of NSAG recruitment and use

Different NSAGs deploy different tactics to engage with young people, and these approaches differ along rural and urban lines.

In urban contexts like Las Delicias, NSAGs begin recruiting between the ages of eight and 15. These groups use young people to serve as informants, collect on bribes and extortion activity, and sell and transport drugs. Young people engage in this work for a variety of reasons, including to obtain new clothes, the latest technological devices, weapons, power, territorial control, cash, or drugs. These forms of work for NSAGs can often allow daily life to continue largely uninterrupted, functioning akin to a contractor model of pay-per-task execution.

While participation in NSAGs was often flaunted in the past – thus tending to attract individuals willing to live with a stigmatised image – my research found that recruitment efforts increasingly target “good” kids because their school records and generally law-abiding status mean that they can operate under the radar of authorities. This approach has been understood by researchers and policymakers as an adaptation to the partially effective persecution of NSAGs by authorities.

Public-sector efforts and challenges

This part-time involvement of young people whose lives otherwise stay within the bounds of legality presents a unique problem for public officials working on preventing recruitment. A National Police lieutenant expressed his frustration with interventions by international actors like the UN, whose staff seemed to assume that nothing had been done to address this problem:

It’s not that we don’t have programmes, or that the kids don’t come. They come, most of the time. But then they disappear for a few days to get done what they need to get done.

Disappearances typically constituted periodic forays into the activities of local neighbourhood gangs, often (though by no means always) involving young men and boys who needed to generate income for the household’s monthly expenses.

Like Dani, these youth have reasonably safe home environments, attend school, have little trouble in their relationships with authority figures, and wish to get ahead in life. However, in contexts of scarcity where extralegal employment is readily available, the dual demand placed on them as students and as providers can easily result in engagement with extralegal options, on a part-time basis at least.

A broader perspective for policy and intervention

Both organisational and policy interventions tend to frame actions in terms of risk factors – those negative, undesirable qualities that lead to certain pernicious forms of social life. More integrated approaches promote positive forms of individual, familial, and community life while also working to ameliorate the negative conditions and behaviours that lead to criminal activity.

What the above demonstrates, however, is that not all youth who engage in NSAG activities can be identified by assessments that convene populations through identification of risky behaviours and negative home environments. As such, I recommend a more holistic approach to studying recruitment and reintegration that accommodates for the fluidity of this mode of participation.

I also recommend a shift in the paradigmatic thinking that tends to drive intervention design. Instead of targeting the “bad” in order to make them “good”, it would be better to focus on those doing bad to be good. These young people represent “low-hanging fruit” for policy makers because they practice a lifestyle that suggests they might well be averse to extralegal activities if structural conditions were such that the need to participate did not exist. The kind of approach would also result in more resilient communities while avoiding resort to repressive methods.

NSAGs in Colombia and throughout Latin America often adopt forms that blur the conventional boundaries between gangs, insurgent groups, civilian communities, and criminal organisations. In part, this is a reflection of their embeddedness in a vast constellation of non-criminal behaviour and complementary and competing desires and understandings of the self and the wider world.

Approaches to research and intervention need to better accommodate these blurred borders and this real-world complexity if they are to ask the right questions – and find the right answers – when it comes to youth participation in non-state armed groups in Colombia and beyond.

Notes:

• The names of individuals, neighbourhoods, and organisations have been changed

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting