Housing security plays a significant role in the decisions made by women suffering domestic abuse. Even when survivors do manage to escape their abusers, social and institutional barriers often prevent them from fully exercising their property rights and leave them homeless, vulnerable, or in danger, writes Raquel Ludermir (Universidade Federal de Pernambuco).

Housing security plays a significant role in the decisions made by women suffering domestic abuse. Even when survivors do manage to escape their abusers, social and institutional barriers often prevent them from fully exercising their property rights and leave them homeless, vulnerable, or in danger, writes Raquel Ludermir (Universidade Federal de Pernambuco).

• Também disponível em português

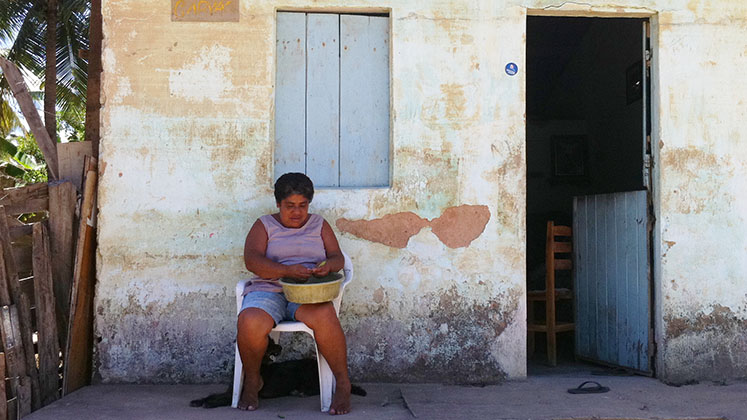

Maria has lived her whole life in the same low-income settlement in Recife, Brazil, and she has experienced domestic violence for years. At first, she refused to leave her home, which she herself had helped to build. Ultimately, however, the violence became so severe that a basic need to survive left her no alternative but to take her children and flee.

There are women like Maria all over the world. Globally, one in every three women experiences domestic violence, often facing a cruel choice between leaving home to survive or continuing to live with the abuser due to a lack of alternative housing.

Though we have much to celebrate today on International Women’s Day 2020, there are still many important aspects of domestic violence that we need to better understand and properly address, not least its relationship to housing security, especially in urban, low-income contexts in the Global South.

How do housing arrangements relate to domestic violence?

My recent research on the housing trajectories of domestic-violence survivors in Recife, Brazil, revealed that they often move into their partners’ family homes when first forming a household. This tends to happen when they get pregnant and are denied access to inheritance or family gifting. Despite the gender neutrality of inheritance laws, gender norms dictate that men should be the ones providing for the new family.

Later, during the marital relationship, many domestic-violence survivors have only a limited ability to contribute directly to housing improvements, as they suffer disproportionately from time and income poverty. In Brazil this should not be a problem, as the default marital regime in the eyes of the law is partial community property, which stipulates that any property acquired during a marriage or consensual union belongs to both partners irrespective of who paid for it.

However, popular understandings of property rights undermine this legal regime, and with it women’s relationship to property. In other words, women tend to own less property than men, and what little property they do own is subject to gendered misunderstandings around property rights.

When domestic violence takes place in these kinds of housing arrangements, women often live in constant fear of being evicted by abusive partners or having to leave their homes to survive. After mapping concrete exit options and available housing alternatives, domestic-violence survivors tend to enter a phase of cyclic evictions, returning home to abusive partners when things calm down or when no longer able to stay at someone else’s home.

More than a third of survivors in the Recife study continued to live with abusive partners. Crucially, the reasons for staying are often related to housing. Some decided to stay to protect their children’s inheritance rights where home ownership was unclear, whereas others were effectively trapped by home ownership: leaving would mean losing their own property, including for many beneficiaries of housing programmes.

Gender Violence Eviction and patrimonial violence against women

Amongst women who did manage to end abusive relationships in the Recife study, very few were able to keep their homes, and these were usually sole owners of the homes in question.

In those cases where the residence was owned by both partners, women who tried to keep the marital home experienced the most severe forms of violence, including death threats and serious physical injuries, with in-laws often becoming involved.

The vast majority of women who ended an abusive relationship did so by leaving the marital home, thereby becoming victims of what I term “Gender Violence Eviction”: forced removal from housing as a direct result of domestic violence.

In these cases, domestic-violence survivors lost their rightful share of marital property, whereas women who did not own property still lost their right to tenure security. Minimally defined as the protection against forced eviction, tenure security is a fundamental aspect of the human right to adequate housing.

Gender Violence Eviction is a form of patrimonial violence against women, which is to say the violation of women’s property and housing rights. This is a specific form of gender violence that is already recognised in the legal frameworks of Latin American countries like Brazil, Ecuador, and Mexico.

Yet in Brazil, for instance, patrimonial violence against women is still poorly reported. Such cases typically involve low-income, black/brown and indigenous women who may not be fully aware of their property rights and as such cannot always identify and prosecute related violations.

Police and court officials tend to focus on the most obvious forms of violence, such as physical and sexual violence, while overlooking housing- and property-rights violations as a form of gender violence. Moreover, even in contexts of domestic violence, property-settlement cases are dealt with in civil courts rather than domestic-violence courts, which serves to detach property settlement from the gender violence in which it is rooted.

Impacts of domestic violence: homelessness, housing inadequacy, and beyond

In all of Brazil, a country of more than 200 million people, there are a mere 70 domestic violence shelters. These few shelters are accessed only by women already exposed to the most severe stages of domestic violence, such as death threats. Neither is there a social housing programme that offers a concrete exit option for women fleeing domestic violence.

As a result of this limited government response to the housing needs of survivors, women fleeing domestic violence often turn to family members and friends when trying to relocate. In shared housing arrangements, women’s vulnerability to forced eviction depends on their relationship with the head of the household, and many live in constant fear of having to leave again.

Those few women that can afford to fall back on the rental market often face an excessive rent burden. As such, the security of their living arrangements depends on their ability to earn a steady and sufficient income. This can prove extremely difficult, especially for those who are also effectively rendered single mothers.

Meanwhile, survivors who relocate to places familiar to their abusers, such as their own family home, face continuous harassment from former partners. Living in overcrowded, precarious homes – such as single-room dwellings for multiple families, or houses whose bathrooms lack doors – there is also a greater risk of child abuse, which is indicative of the intergenerational impact of gender-based domestic violence.

The key issue, ultimately, is that women like Maria are real, and their struggle for adequate housing and lives free from violence is much more complex than we currently acknowledge. To help them achieve that aim, we must advocate for integrated policies that properly address the housing needs of domestic-violence survivors, as this represents a crucial but largely overlooked means of weakening the grip of gender-based domestic violence.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting