The impact of the coronavirus crisis on livelihoods and prices has limited access to food in Brazil, particularly for those on lower incomes. Supply chains that fail to cover the “last mile” into poor urban communities are a significant part of the problem, and impressive community initiatives to meet nutritional needs are not enough to bridge that gap. So far the issue of food security has been used by the current government mainly for political point-scoring, but there are real steps that it could take to achieve a more resilient, fairer, and healthier food system, write Gareth A. Jones (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre), Aiko Ikemura Amaral (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre), and Mara Nogueira (Birkbeck, University of London) as part of a series of blogs linked to their British Academy-funded project Engineering Food: infrastructure exclusion and “last mile” delivery in Brazilian favelas.

On April Fools’ Day, Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro tweeted a video of a near-deserted regional supply centre in Belo Horizonte. “Take a look at this”, said the man in the video. “This is what we call a food short–age!”. Bolsonaro’s own caption added that “[This is not about] a disagreement between the president and SOME state governors and SOME mayors”, claiming that the video showed “some facts and truths that must be revealed”.

This video depicting supposed food shortages in Belo Horizonte was shared by President Jair Bolsonaro, but it was later found to be false

Bolsonaro’s brief encounter with the “truth”, however, ended only hours later when journalists visited the supply centre and found it operating as usual. It later emerged that the video had deliberately been shot while the market was being cleaned and therefore empty. Bolsonaro later apologised and deleted the tweet, but its message had gone out loud and clear. The food supply chain had become politicised, and it was now one more issue – like promoting treatment with chloroquine or rejecting social distancing – that he could use to fire up his ever-ardent supporters.

Beyond Brazil, steps to control the pandemic have led to a renewed focus on the resilience of food supply chains, raising important questions about availability and accessibility of food. Complex, time-sensitive supply chains, like those providing fresh fruit and vegetables, suddenly begin to look too long and too fragile. Policy advice has highlighted logistical solutions that could ensure future supply chains are more resilient and efficient. But missing from this discussion, and from controversy around Bolsonaro’s “shortages” video, has been a consideration of the actual politics of food insecurity and its far-reaching effects on health and wellbeing.

COVID-19, food security, and a health syndemic

Even before the pandemic, the impact of extreme weather events, conflicts, and persistent poverty on global food systems had led UN agencies to highlight the growing problem of food insecurity. But COVID-19 threatens to make the problem even worse, especially for the poor and vulnerable, including the elderly and lower-income households with children.

Widespread job losses and rising prices during the crisis put pressure on people’s ability to acquire food of sufficient quantity and variety. And when healthy foods are substituted with high-calorie, ultra-processed options, rates of undernutrition and obesity are exacerbated, which effectively serves to store up negative public health outcomes. COVID-19 has highlighted how vulnerable populations are negatively impacted by the complex interaction of socio-economic exclusion, low-nutrition diets, diagnostic markers indicating compromised immune systems, and policy decisions that provide uneven access to underfunded health services. This situation can be viewed as a syndemic: a complex web of illnesses, social factors, and environmental influences that promotes the negative effects of disease interaction.

Leading up to the coronavirus crisis, data for Brazil showed that high levels of undernutrition and obesity were co-present with associated diseases such as diabetes, cardio-respiratory conditions, and some cancers. These conditions have persisted despite numerous public policy interventions. During the 2000s, a combination of economic growth, decreasing inequality, and targeted public policy (particularly the Zero Hunger programme) led to improved nutrition but also rising obesity. Once economic growth slowed, indicators for both nutrition and obesity worsened. The 2020 Global Nutrition Report showed Brazil was on track to miss all of its nutrition targets for 2025.

While the process of nutritional transition has been extensively analysed, only recently have discussions focused on food security in cities, especially for low-income residents. Our ongoing research project examines the availability, accessibility, and consumption of fresh food in favela neighbourhoods in Belo Horizonte and São Paulo. In both cities, business models have produced supply chains that do not close the “last mile”, failing to provide sufficient fresh food to favelas. Instead, residents buy food from street markets and “mom and pop stores”, or from supermarkets outside the favela, often during long return journeys from work. It is common to observe people, and especially women, carrying heavy loads, sometimes at night, on uneven pathways or up steep slopes. Acquiring food is a daily struggle for the urban poor.

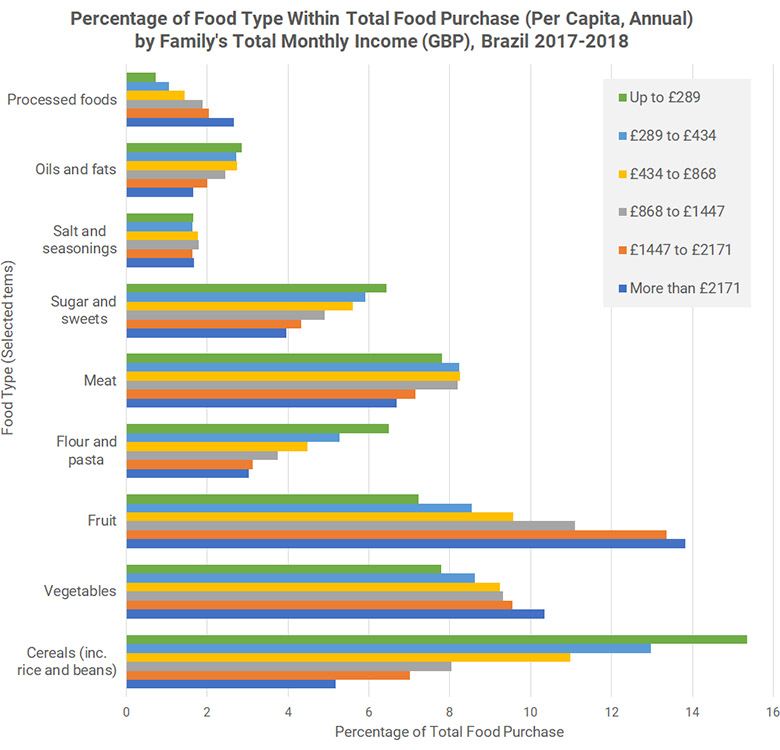

The food burden is also an economic one, as budgetary constraints and limited storage options only allow for shopping in small quantities at higher unit prices. According to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, families in the lowest income bracket spend almost four times more of their monthly income on food than those in the highest income bracket. This spending does not translate into a more balanced diet, however, as the proportional consumption of fruit and vegetables for people in lower-income brackets is far lower than for those with high incomes (as illustrated below).

Adopting the idea of “people as infrastructure“, we find that social networks provide opportunities for people to borrow food, to look after each other during sickness, or to mind children and other relatives. A diverse array of actors – civic organisations, religious groups, political activists, trade unions, social entrepreneurs, and criminal networks – operate, collaborate, and improvise to “engineer” food availability for vulnerable households. This dense network has set up community kitchens, urban gardens, food banks, savings schemes, and waste recycling projects, with many also seeking to raise awareness of nutritional issues and organic food. These interventions are inherently, and sometimes explicitly, political actions. They respond to supply-chain models that perceive favela communities as “economically inviable” or excessively violent. This common disconnect from favela realities has tended to reinforce other inequalities, such as unequal economic power, limited state services, and citizenship rights.

Tackling the food crisis under COVID-19

The unfolding COVID-19 food crisis has highlighted cleavages of economic, social, and political power, as well as their intersections with gender, race, and class. Poor households have struggled to make ends meet, with further pressure on already precarious livelihoods leading to lower food consumption. Without refrigerators or the money to pay for electricity, households are unable to store food or plan meals. School closures during lockdown, meanwhile, have made it harder for parents to go out to work, deprived children of free meals, and increased domestic food bills.

Supply chains for processed foods have been less affected than for fresher and healthier foods, especially where more vulnerable urban households are concerned. Crowded streets and wholesale markets have become vectors for COVID-19, with nearly 80 per cent of vendors in some Latin American markets becoming infected. Politicians have found themselves in a bind: leave markets open to protect livelihoods and food supply, hoping to dodge awkward questions about why sanitation conditions are often inadequate, or enforce lockdown measures and take the political hit.

Instead, food supply has been supported by a series of extraordinary measures. Civil society organisations, church groups, unions, universities, private companies, and individuals have mobilised to deliver food parcels to needy households. Community kitchens in neighbourhoods across Brazil have been supplied by social movements and farm cooperatives, supporting the provision of basic meals and delivering lunch boxes for takeaway. Even criminal groups have become involved, sometimes forcing shops to remain open or distributing food parcels.

These responses are short-term interventions in an urgent situation. They tackle the immediate threat of hunger, but they neither solve inadequate and disrupted supply chains nor combat widespread undernutrition and obesity. Most food parcels consist of items that are easy to transport, distribute, and store. But long-life milk, biscuits, and “dry goods” like rice, pasta, and noodles provide a particularly carbohydrate-heavy diet. These interventions could also undermine the social infrastructure upon which local people generally rely, not least by jeopardising the livelihoods of “mom and pop stores” and market traders.

Building sustainable food systems after COVID-19

So what would a more resilient, more equitable, and healthier food system look like in the long term?

First, there are innovative ways to make supply chains shorter and more diverse. Low-friction farm-to-fork chains, already heralded as a viable response in the US, can deliver benefits like adaptability to sudden shocks and lower carbon footprints. In São Paulo, meanwhile, our co-researchers are working in collaboration with a social enterprise called Frexco in an effort to use logistical solutions to enhance the circular economy between peri-urban small producers and urban consumers. The dual purpose of this initiative is to improve the provision of fresh food while strengthening livelihoods along the supply chain.

Second, we will have to gain greater insight into how people engineer their access to food, especially under conditions of extreme precarity. How do people move across different networks, set preferences, improvise practices, and share knowledge around food? Lacking this information, interventions that aim to improve access in favelas and increase the involvement of private supply chains will fail to meet people’s needs.

Third, we need to raise awareness of balanced diets and identify the barriers that poorer people especially face in acquiring and consuming fresh food. While budget constraints matter, data show low levels of interest in fruit and vegetables across all social groups in Brazil. Wider public policy should also consider and integrate the Food-Based Dietary Guidelines set out by the Ministry of Health and Pan American Health Organization. More specifically, past experiences of food awareness programmes (as once used in Belo Horizonte, for example) should be revisited, with local practices and preferences incorporated into their development and implementation.

Fundamentally, however, building sustainable food systems involves contentious political decisions: as the coordinator of a São Paulo organic food shop maintained by the Landless Movement recently noted, promoting good dietary practice is a political act.

The threat of food shortages, as symbolised by the supposedly empty supply centre in Bolsonaro’s tweet, highlights the gap between the haves and the have-nots. Bolsonaro and his economy minister Paulo Guedes have exploited this politics of food and subsequent “social disorder” to raise the pressure on state governors to lift lockdown measures.

But although a focus on supply chains is overdue, for now the Brazilian government continues to dodge the thornier underlying issue: that the social inequalities revealed by COVID-19 must be addressed if people’s need for affordable, reliable, and health-appropriate food is to be met in the years ahead.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article is part of an ongoing project entitled ‘Engineering Food: infrastructure exclusion and ‘last mile’ delivery in Brazilian favelas’, which is funded by The British Academy under its Urban Infrastructure and Well-Being programme.

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting