Severe delays and mid-construction abandonment have long been serious problems for infrastructure projects in Latin America, but coronavirus appears to be making things even worse. The case of sewerage works in Peru shows that this isn’t just about wasting public money; it’s a matter of life and death, write Antonella Bancalari (LSE Social Policy) and Oswaldo Molina (Universidad del Pacifico, Peru).

Severe delays and mid-construction abandonment have long been serious problems for infrastructure projects in Latin America, but coronavirus appears to be making things even worse. The case of sewerage works in Peru shows that this isn’t just about wasting public money; it’s a matter of life and death, write Antonella Bancalari (LSE Social Policy) and Oswaldo Molina (Universidad del Pacifico, Peru).

The COVID-19 crisis is devastating the economies of low- and middle-income countries around the world, but one issue that has received relatively little attention is the reduction in progress of infrastructure projects. Even in normal times, half-finished infrastructure projects are a common sight in most Latin American cities. But today, with the virus sweeping across the region, a half-built hospital matters more. In Peru specifically, measures adopted to contain the spread of COVID-19 appear to be aggravating the longstanding issue of mid-project abandonment.

Understanding project progress during COVID-19

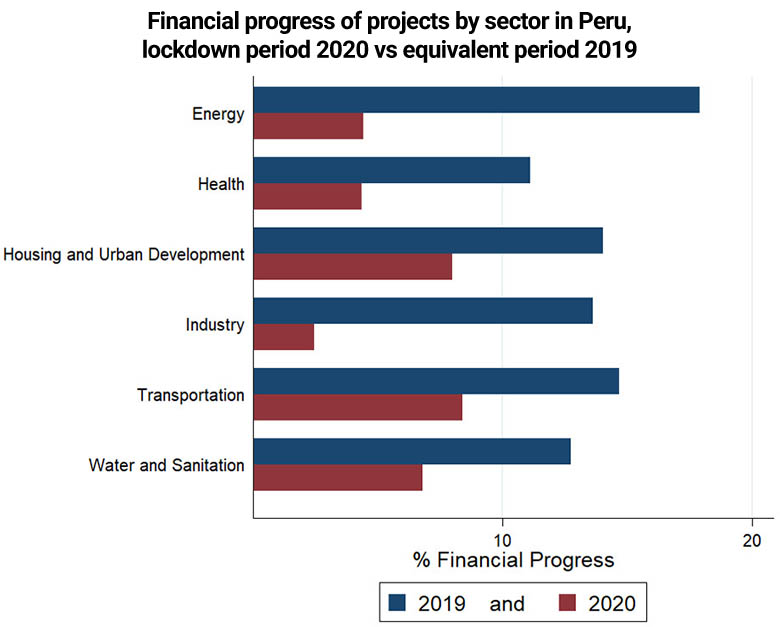

In order to gauge the extent of this issue, we compared the financial progress of projects in key sectors between March and May 2020 – covering the strict lockdown period – with progress during the same period of the previous year.

Our analysis reveals a worrying degree of mid-project abandonment. During the lockdown period, the government of Peru made only half of the financial progress that it had managed during the same period in 2019, although the magnitude of this difference varies across sectors (as illustrated below). Energy and industry, meanwhile, experienced reductions in progress of 75 and 82 per cent respectively. Strikingly, progress in a key sector like health fell by 61 per cent, whereas other important sectors like transportation, water and sanitation, and housing and urban development saw reductions of over 40 per cent.

This slowing of projects due to COVID-19 also carries an additional risk: that projects are never completed. Given the potential for degradation of work already completed, relocation of machinery and labour, exposure to bureaucratic and legal processes, and bankruptcy of private contractors, even a temporary halt increases the chances of mid-construction abandonment. And as has recently been shown by research from Antonella Bancalari, unfinished infrastructure projects are more than just a waste of public resources: they have real impacts on public health and can even lead to the needless deaths of many children.

Unfinished sewerage projects and child mortality

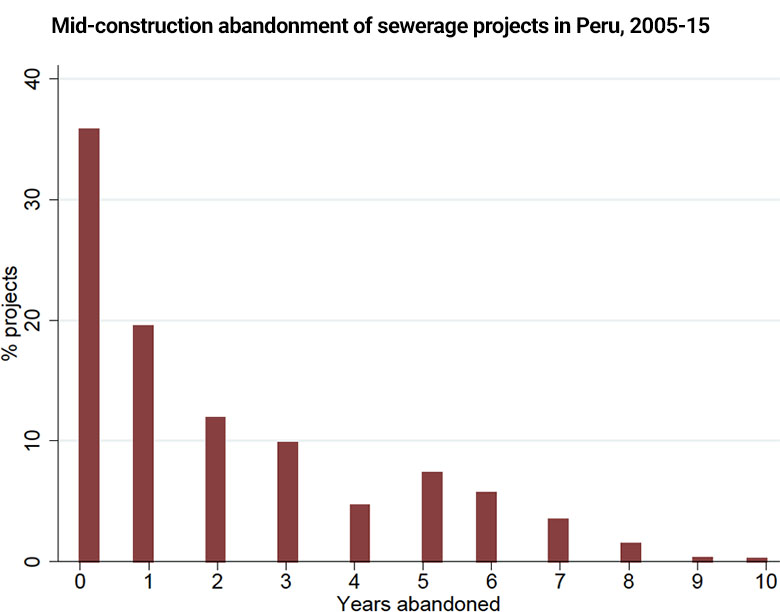

Recognising that sewerage systems improve public health, the government of Peru invested USD 3 billion in 6,000 sewerage projects between 2005 and 2015. Strikingly, 65 per cent of the projects started in this period were abandoned at some point. While 20 per cent were halted for a single year, more than 40 per cent were abandoned for at least 2 years, and some indefinitely.

Interviews with local engineers indicate that we might expect an average sewerage project to be completed in one year, but in practice delays are frequent. For projects started and completed between 2005 and 2015, 10 per cent were completed during the first year, 25 per cent during the first three years, and more than half were completed five years or more after they started.

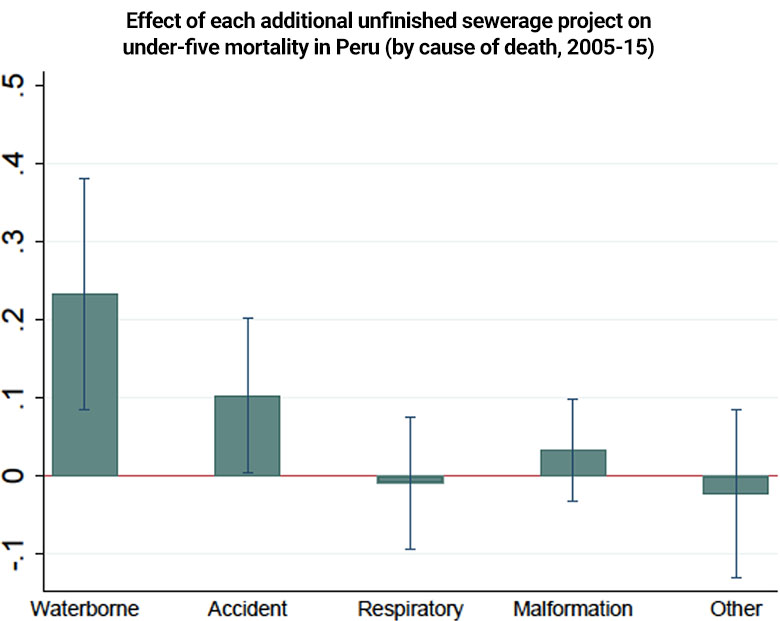

Using econometric methods to analyse the roll-out of sewerage projects alongside a compilation of several novel sources of administrative data for 1,400 districts, recent research has been able to estimate the effect of unfinished sewerage projects on the mortality of children under the age of five.

This analysis, carried out by one of the authors of this article, found that with every additional unfinished sewerage project, under-five mortality increased by 6 per cent over the baseline level. The mechanisms behind these non-trivial effects are threefold:

- The installation of public sewers requires extensive excavations. This often leaves open ditches to become filled with stagnant water, creating the conditions for infections to thrive. Neighbourhoods sometimes became infested with mosquitoes, and there were even cases of under-fives drowning in pits of stagnant water as much as two metres deep.

- Sewerage diffusion involved large building sites that diverted traffic haphazardly into previously quiet residential areas where children roam freely.

- Water cuts required during the installation of sewerage systems forced the population to rely on unsafe sources of water and led to a degradation of hygiene and sanitation practices.

Owing to these mechanisms, the study found that for every additional unfinished sewerage project, under-five mortality caused by water-borne diseases and accidents increased by 10 per cent over baseline levels, with no effect on deaths from unrelated diseases.

Reactivating the economy after the pandemic

If delays and mid-construction abandonment of infrastructure projects were troubling before COVID-19, they will only be more so once Latin American countries start to reactivate their economies. Serious planning for the second half of 2020 must take into account this challenge. It will be essential to try to overcome these additional setbacks in the progress of infrastructure projects, but this is a far from trivial task for overstretched local and national governments.

The state will need to do its best to streamline public expenditure. The programme Arranca Peru, part of which covers construction and maintenance of transport-infrastructure projects, serves as a useful example, offering quick disbursement of funds and the potential to secure or increase employment. Government-to-government technical-assistance agreements, such as the one Peru has just signed with the United Kingdom, constitute another powerful means of developing infrastructure effectively and efficiently.

That said, mid-construction abandonment of infrastructure projects is a long-term problem, and a longer-term solution will require a far better understanding of the cost-effectiveness of supplying public infrastructure. This kind of analysis should include social costs as well as private costs; this would incentivise stakeholders to mitigate otherwise the invisible effects of infrastructure projects on the real lives of real people.

Project delivery, for example, could be complemented by policies that mitigate the negative consequences of construction. Stricter health and safety measures, free healthcare, and the provision of safe alternative sources of water and sanitation are all low-hanging fruit that could compensate affected populations and prevent child deaths.

Finally, institutional arrangements both public and private will have to tackle the often chaotic nature of infrastructure financing and construction. At the very least, governments must improve the monitoring of the material progress of infrastructure projects. Ultimately, unnecessary delays and mid-construction abandonment exacerbate health hazards to the population and must be moved up the ladder of policy priorities.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

It is an interesting article that highlights one of the many problems surrounding infrastructure development in developing countries like Peru (the project`s quality is another big problem), but I think it is not accurate to make conclusions about delays in sewerage projects just with the superficiality opinions of some engineers. Every sewerage project is different, not just for its dimetions, also due its own complexity. It could be better If you take as a base line the planned duration of each sewerage project, this data is also available.

I was able to catch some useful insights.

Thank you for writing this article.

Thank you José for your comments. You are absolutely right that the way I measure delays in my study is second-best. Unfortunately, there is no data in Peru available for each project about the planned duration. That would’ve been optimal to qualify it accurately as delays. I do, however, run an analysis of project duration by project type and still find large variation in time to completion.