Data from Latin America and the Caribbean shows little cause to celebrate World Press Freedom Day, which this year is recognised by a global conference in Uruguay. But amid the bleak figures are also the indications of how the region can find a path back towards media development, explain Ivette Yáñez (Data-Pop Alliance) and Nick Benequista (Center for International Media Assistance and LSE).

According to UNESCO’s recently published World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: Global Report 2021/2022, more journalists were killed in Mexico (61) than in any other country between 2016 and 2020. The number of journalists killed in the entire region over that same period was 123 (a figure matched only by the Asia and Pacific region, which has over six times the number of inhabitants). Moreover, while some regions have shown improvements in the past decade, LAC numbers have remained nearly unchanged (122 journalists were also murdered between 2011 and 2015).

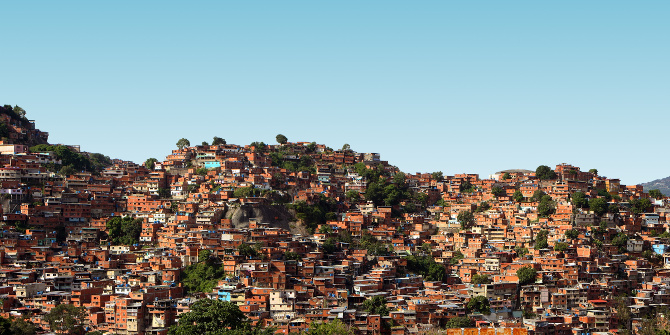

While the threat of violence to Latin American and Caribbean journalists is perhaps the most shocking, access to free, independent, and pluralistic media faces several challenges in the region. As elsewhere, digital advertising markets have undermined the commercial foundations of journalism. While journalistic entrepreneurs still find ways to fund their work, news deserts are a growing concern, including in Brazil and Colombia.

Along with this new digital landscape, journalists also face new threats. Commercial spyware, including the sophisticated Pegasus spyware, has been used against journalists in Latin America. Access Now and the #KeepItOn coalition have already reported internet shutdowns in Colombia and Brazil in the midst of the election campaigns taking place this year in both countries. Online violence against female journalists has been another prominent issue in the region.

As in many other sectors, the Covid-19 pandemic has only exacerbated existing issues and inequalities in journalism and media, either by providing a justification to push new legislation that curtails access to information or by setting the grounds for enacting other forms of restrictions on press freedom. Between February 2020 and May 2021, the IPI’s COVID-19 Press Freedom Tracker identified 38 cases of censorship on media or journalists covering Covid-19 (i.e. websites blocked, forced closures of media outlets, publication bans) in the Americas, the largest number across the 5 world regions. It also documented 45 incidents of verbal or physical attacks against journalists working on pandemic-related stories in the same region—data was aggregated for North America and South American countries.

Solutions to protect press freedom

The situation appears bleak, but as new techniques of censorship emerge, so too do innovative solutions to foster and protect press freedom. The first step is to have a better understanding of each of the challenges. That requires measuring and monitoring, which in turn demands quality data. The power of data can help to protect journalists and their work, promote policies and legislation that protects press freedom, bolster the viability of news media in the digital age and ensure access to free, independent and trustworthy media.

Some of the projects and organisations currently paving the road towards greater press freedom (often with data) in Latin America and the Caribbean include Voces del Sur, whose work during the last couple of years has centred around monitoring the number of journalists who have been killed, kidnapped, detained, disappeared, tortured, and physically and orally attacked. The initiative has also underlined the restrictions on access to information, news containing “stigmatising discourse”, changes in the legal framework, cases of power abuse by the State, and restrictions on the internet across 14 Latin American countries and the Centroamerican region. Latam Chequea, a project coordinated by the fact-checking initiative Chequeado with contributions from 35 other organisations, has also focused on the pandemic effects, specifically the so-called “indofemic” or “disinfodemic” by providing an open data platform with thousands of verified news from the region.

Another data-driven initiative worth mentioning is the Latinobarometro, a public perception study that has been conducted annually across 18 Latin American countries for over 25 years. Though not exclusively focused on matters of press freedom, the survey covers questions about perception on this topic, as well as the use of digital technologies for accessing news.

In terms of legislation, the Centre of Studies in Freedom of Expression and Access to Information (CELE, in Spanish) is doing exceptional tracking changes in relevant legislation for the region. Through their project, Observatorio Regional: Legislación en Libertad de Expresión en América Latina [Regional Observatory: Legislation in Freedom of Expression in Latin America], CELE has analysed and categorised the impact of over 300 laws and 1100 law projects going back to 2007 and up to 2021. Derechos Digitales América Latina has developed similar work, but from a more qualitative approach, studying the regulatory issues affecting freedom of expression, press freedom and the internet on freedom of expression and the internet. Other organisations doing robust research work on circumventing issues such as media concentration, pluralism, freedom of expression, digital freedoms and violence against women journalists are Observacom, Observatorio de la Democracia and INTERNETLAB.

More initiatives to safeguard the press

Despite these efforts, where journalism is most at-risk, less is usually known about the systems that underpin media freedom. As argued in UNESCO’s World Trends Report, the data ecosystem within the journalism and media sector needs to be strengthened by ensuring availability, accessibility, utilisation, and stability of data sources. It is not surprising that some of the most comprehensive and prominent data-driven initiatives pertain to organisations and institutions of the Global North, particularly within the European Union.

It is also critically important to engage governments in the development of research and data initiatives concerning press freedom and media development, rather than continue to let the burden fall on the shoulders of civil society organisations.

This year’s World Press Freedom Day should provide a wake-up call to governments in the region that have embraced international democratic norms, but failed to safeguard the press. The first step towards a solution, it is often said, begins by acknowledging you have a problem. The second step should be a commitment to collecting the data that can pave the way to a stronger news sector.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

• Banner image: Paul Sableman (CC BY 2.0)