As in the rest of the world, trust in news in Latin America has declined in recent years. But survey data from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico show that trust levels vary significantly from one national context to another and can relate to a variety of phenomena, from the shortcomings of journalism itself to social unrest or antagonism between politicians and journalists, write Camila Mont’Alverne, Amy Ross Arguedas, Benjamin Toff, and Sumitra Badrinathan (Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, University of Oxford).

• Disponible también en español

Low levels of trust in news media have long been a cause for concern in many democracies, as the media can help to keep citizens informed, encourage political engagement, and serve as a watchdog for abuses of power. However, the first report of our Trust in News Project at the University of Oxford’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism shows that trust in news has been eroding all around the world. Democracies in the Global North – and particularly those where trust tended to be highest in the past – are now experiencing declining levels of trust in news.

But Latin America is quite distinct. This is a context that has historically grappled with corruption and political instability, with a news ecosystem often criticised for concentration of ownership, political clientelism, and a consistent failure to represent diversity. So how do changing levels of trust in media play out in contexts like these, where generating trust in institutions has long been a challenge?

To answer this question, we analyse trust in news in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico against the backdrop of wider global trends. Using online survey data from the Digital News Report (DNR) between 2017 and 2020 allows us to examine how people in each of these countries rate their trust in news generally and also their trust more specifically in the news that they themselves consume.

Do Latin Americans trust the news?

The news landscape in Latin America is characterised by heterogeneity, with highly disparate newsgathering practices and professional values across the region. Furthermore, trust in news is a complex and context-specific phenomenon, which can be shaped by a variety of factors, both intrinsic and extrinsic to journalism itself. It is thus unsurprising that the levels of general trust in news during the three years analysed do not exhibit a clear or consistent regional pattern.

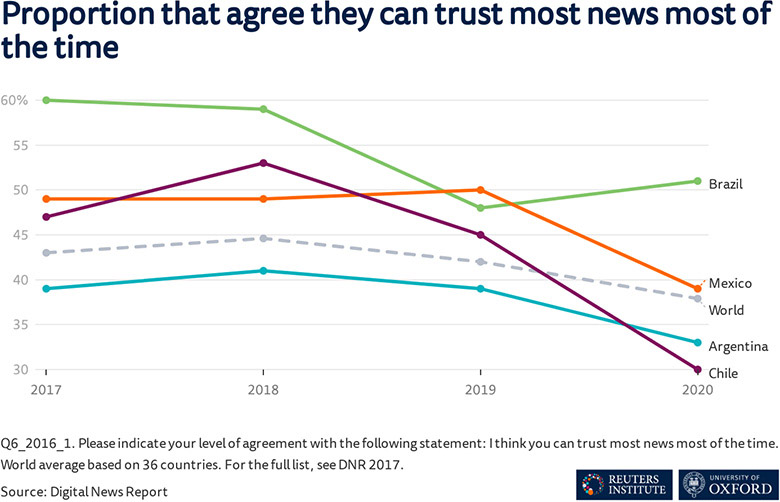

While all four countries had lower overall levels of trust in 2020 than they did in 2017, they displayed different trajectories. In line with the global trend, Argentina and especially Chile suffered significant and sustained decreases in trust in news over the three-year period. The percentage of the population claiming to “trust most of the news most of the time” dropped by a total of eight and 23 percentage points (pp) respectively, putting both countries below the world average (itself already low at 38% in 2020). In contrast, trust in news in general fluctuated in Brazil and Mexico, with Brazil suffering a significant decrease (11pp) followed by a very small increase (3pp), whereas Mexico experienced a slight increase followed by a significant drop in 2020 (11pp).

Large drops in trust in news, such as those documented between 2019 and 2020 in Chile and Mexico, are often linked to the broader socio-political context. As such, significant social unrest during this period – mass protests in the case of Chile and widespread concern about organised crime and the economy in Mexico – may have contributed to these dips in trust in news in general. After all, trust in news is often linked to trust in institutions more generally. Ongoing attacks on the news media by politicians, a tactic deployed by Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and more recently by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, may also contribute to decreases in trust and polarise attitudes towards the press along partisan lines. Nonetheless, both countries still show relatively higher levels of trust than the world average, especially Brazil. Meanwhile, Chile stands out for the fact that trust in news went from being above the world average to dipping significantly below it, with its citizens expressing in 2020 the lowest degree of trust observed across all four of the Latin American countries covered here.

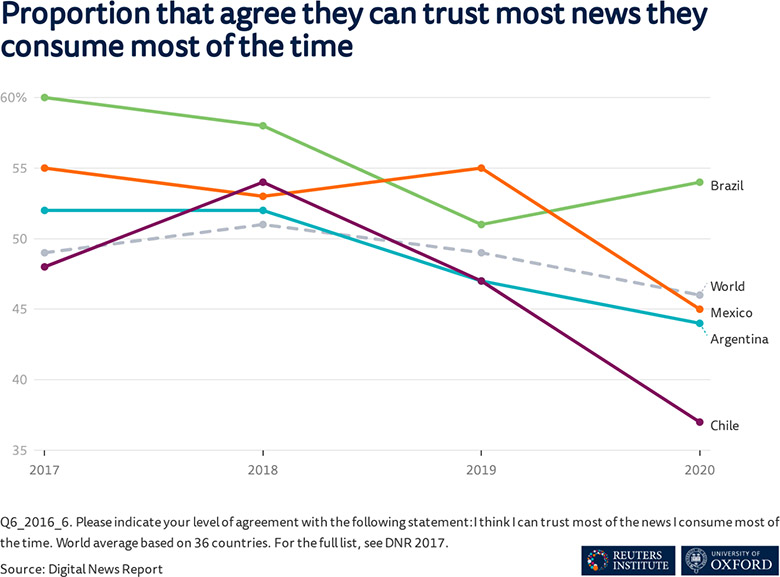

Unsurprisingly, people tend to report greater levels of trust in the sources of news that they use compared to news in general. However, the same national trends that we observe in general trust repeat themselves when we look at trust in the news that people consume, suggesting that perceptions of the two are connected, even if the baseline of the latter is higher. The waning percentage of citizens that feel they can trust most of the news that they consume further highlights the erosion of Chile’s trust in news: over the course of three years, almost 20% of Chileans lost trust even in the news that they consume. This tallies with the fact that the news media themselves became targets during massive demonstrations against inequality. Argentina also exhibits a loss of trust in the news people use in 2020 when compared to the previous year, which may be connected to the transition between the Mauricio Macri and Alberto Fernández administrations. Although Fernández tends to avoid confronting the media, some of his supporters have a deeply rooted distrust of the country’s major media organisations. It is possible that the Peronistas have become more outspoken about this since returning to power, which may help to explain the recent loss in trust, given that there has been no large shift over the years in the news sources that Argentines are using.

Worries about misinformation by politicians, but also by journalists

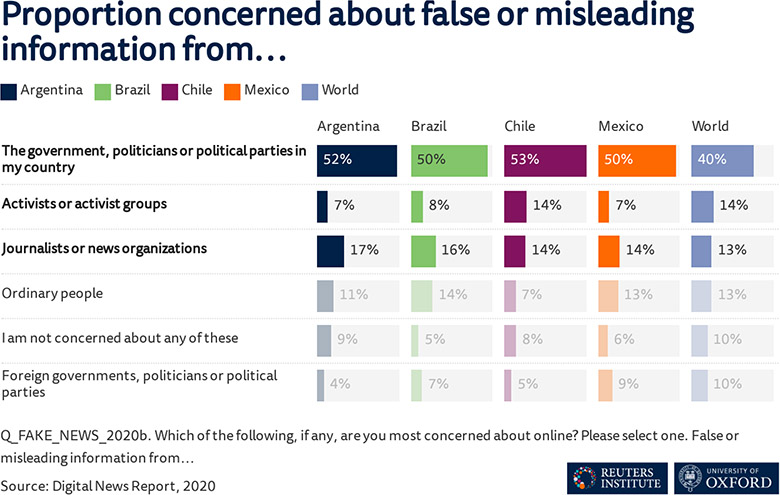

At a time of acute anxiety over the impact of fake news, understanding who is assigned blame for online misinformation can help us to understand how people perceive their informational context and its shortcomings. Data from the 2020 DNR show that in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico, the government and political leaders are by far the most cited sources of concern about false or misleading information online, with about half of the citizens of each country expressing this sentiment, compared to four out of ten worldwide.

Though this could be seen as stemming from the rise of populist presidents in Brazil or Mexico, criticism of handling of Chile’s social protests, or opposition to Alberto Fernández in Argentina, in reality distrust in leaders and institutions has been a common theme in Latin American history. As such, these findings cannot simply be attributed to promotion of divisive content by some leaders on social media, as they may also be linked to longstanding feelings of distrust in these societies. Higher-than-average levels of concern about misleading information from leaders in all four countries may indicate that scepticism about political statements online could be related to attitudes towards authorities in other spheres. Perhaps the novel point is not that Latin American citizens are especially sceptical of their leaders, but rather that this distrust has spread to other countries as well, with so-called “established democracies” becoming increasingly susceptible to similar dynamics in their own information environments.

After political leaders, the second most concerning source of false information for all four countries is “journalists or news organisations”, with scores edging slightly higher than the world average. Although concerns about misinformation from journalists are far less common than concerns about misinformation from leaders, this number is worth following in years to come. Surveys such as Latinobarómetro often suggest that the media constitute one of the region’s most trusted institutions, but shifts in the political and media environment could soon change that. The anger of anti-elite movements targeting political leaders could easily shift towards journalists and news organisations, who are frequently accused of being part of the same group as “mainstream” politicians. It is also worth mentioning that Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico present similar levels of concern about journalists spreading misleading information as we see in the rest of the world, indicating that this could be a global trend.

Journalists and politicians compete for citizens’ trust in Brazil

Moving beyond survey data, we have been able to glean additional insights from interviews with journalists in Brazil, who are by now quite accustomed to being seen as a source of misinformation. Our interviews with 34 practitioners from a range of organisations for the first report of the Trust in News Project found significant concerns about the perception that journalists provide fabricated or untrustworthy information – claims that are often instigated by politicians.

One reporter working for a Brazilian newspaper told us that while distrust in journalism is nothing new, the difference now is that authorities attack the media and accuse it of being responsible for disinformation: “Regardless of whether you agreed or not with coverage, everyone agreed that the press was fundamental for democracy … For the first time, we see this changing, with part of the people and the government accusing the media and suggesting it could be dispensable”.

The President of the Brazilian Newspaper Association (ANJ), Marcelo Rech, expresses a similar concern. He argues the problem is not the criticism of journalists’ reporting but rather disinformation about it, which aims to make people dismiss information that a particular politician or political group finds unflattering: “This comes from an organised attack against press credibility, which is its only asset, and against the moral integrity of analysts, systematic attacks against reporters, editors, and independent professionals … This happens all the time all over Brazil”.

Offering a different perspective, a television reporter, who asked to be quoted anonymously, acknowledges an upside to the increasing scrutiny of journalistic work. Although he underscores that the media were not expecting the aggressive reaction of Bolsonaro and his supporters at the beginning of the current administration, he argues that this “also contributes to the work of the press as a whole and for my own work, of being more responsible and double-checking information [because] we face significant demands, and this increases our sense of responsibility when publishing something”.

Overall, declining levels of trust in news pose a challenge to journalists around the world. Though Latin America is no exception, neither is there one single trust problem or trend in the region. As this analysis suggests, changes in trust levels vary significantly from one national context to another and can involve a broad variety of phenomena, from the shortcomings of journalism itself to social unrest or antagonism between politicians and journalists. Any effective strategy to cultivate trust in news will require us to understand how this trust relates to other social processes in specific and different national contexts.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting

I just thought I would mention that I’ve used the DNR to track trust in Brazil and coupled it with Latinobarametro and there was a correlation. It’s also a great comment by the Brazilian reporter, however, I would argue that in Brazil they tend toward disproportionately fact-checking Bolsonaro and inadvertently underplaying the influence his congressional supporters wield on the spread of fake news.