From student numbers and their curriculum to wartime service and Zeppelin raids, LSE was transformed by the demands of war. Professor David Stevenson investigates the impact of the First World War on LSE.

On the eve of the First World War, in the academic year 1913/14, 1,681 students were enrolled at the School. Many came from overseas, and 583 were women. LSE was well established as a small, niche college of the University of London, specialising in social science research and in evening and vocational education. Among its vocational students were over 300 railway administrators, who were paid for by Britain’s railway companies, and an annual cohort of army officers (totalling over 250 between 1907 and 1914), who were paid for by the War Office. In 1914 the officers were immediately called up, and most spent the next four years on staff work, supply, and logistics.

In other respects after war broke out the School changed more gradually. Special lectures discussed the conflict and its background, and the students paid for a catering van that went to the Front. Refugees arrived from Belgium and Russia. Over 200 staff and students did military service. During training several continued to attend their courses while wearing uniform, but by the end of 1915 most had gone abroad. Other members of the School community worked for government agencies in Britain, in economic intelligence, as factory inspectors, or as food administrators.

During Zeppelin raids students sheltered in the basement or went out to watch the spectacle; in a 1918 bomber attack the buildings sustained minor damage. Student numbers and fee income dwindled, and the School management struggled to find replacement teachers. The Director, William Pember Reeves, became a recluse after his son, Fabian, was killed while flying over France, and much of his work devolved to the School Secretary, Christian MacTaggart. Nonetheless, throughout the war LSE continued to function.

Several members of the School community had notable wartime careers. Before 1914 R H Tawney, the economic historian and Christian socialist, had held an administrative position. He served in France and was wounded when going over the top on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, an experience of which he published a graphic description.

Hugh Dalton, the future Chancellor of the Exchequer, was a postgraduate student who served with the heavy artillery in France and Italy, where he was decorated.

Clement Attlee, who had beaten Dalton in the selection process for a lecturing post in 1912, also volunteered (despite being over the normal maximum age of 30). He was the last man but one to evacuate the Gallipoli beachhead in 1916, and was twice wounded. All three men would return to the School’s teaching staff, though Attlee only briefly as the war had changed him and he soon launched into a full-time political career.

At home, LSE co-founder Beatrice Webb served on the government’s Reconstruction Committee in 1917-18, steering it towards ambitious recommendations for social welfare reform. Her husband Sidney, besides remaining a pivotal member of the School’s Court of Governors, was deeply involved in the Labour Party’s wartime transformation. He commissioned a pioneering Fabian Society study of the League of Nations and helped to draft not only the party’s platforms on foreign policy (the “Memorandum on War Aims”) and domestic policy (“Labour and the New Social Order”) but also the celebrated socialist commitment in “clause four” (actually clause 3d) of the 1918 Labour Party Constitution, which under Tony Blair would be reworded.

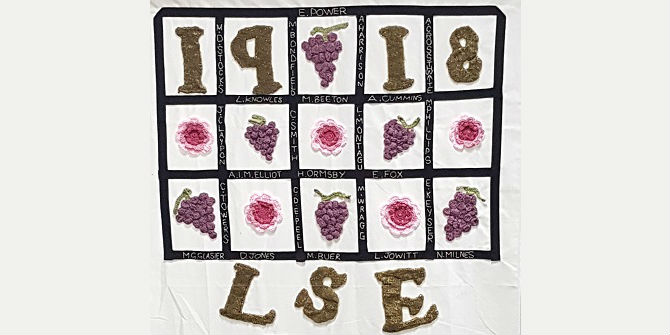

By the final year of the conflict the School’s student numbers and finances were recovering, helped by the presence of some 200 American army officers who took courses in 1918/19 before returning home. Under a new Director, William Beveridge, the 1920s would be a decade of expansion and innovation. Although a memorial was unveiled in 1923 (and replaced by the present one in 1953) to the seventy members of the LSE who lost their lives, the war had a smaller impact than on many other educational institutions.

Yet for the School community’s role in British national life – particularly through its influence on the Labour Party at a crucial phase in its development – the significance of the wartime years extended far beyond Houghton Street.

An elegant thumbnail sketch. It would be interesting to know when, or if, the Armed Forces continued to send officers to the School.