LSE’s Library, the British Library of Political and Economic Science, opened in November 1896. In a series of posts celebrating LSE Library’s 120th anniversary in 2016, Gillian Murphy explores the story behind the 1866 women’s suffrage petition.

On 7 June 1866 a petition from 1,499 women calling for women’s suffrage was presented to Parliament. Although this petition was unsuccessful, the Fawcett Society marks this moment as its foundation and the start of the organised campaign for the vote.

What is the story behind the 1866 women’s suffrage petition?

Only a month earlier, on 9 May 1866, Barbara Bodichon had written to Helen Taylor about the possibility of doing something immediately towards getting women votes. She wanted to know what Helen and her stepfather, John Stuart Mill, thought about this idea. Helen wrote back saying that as the Reform Bill was under discussion then it was clear that women who wanted the vote should speak up. She just wondered whether they would get enough signatures. If they did, then John Stuart Mill would willingly present the petition to Parliament. In the previous year, he had endorsed women’s suffrage during his successful election campaign.

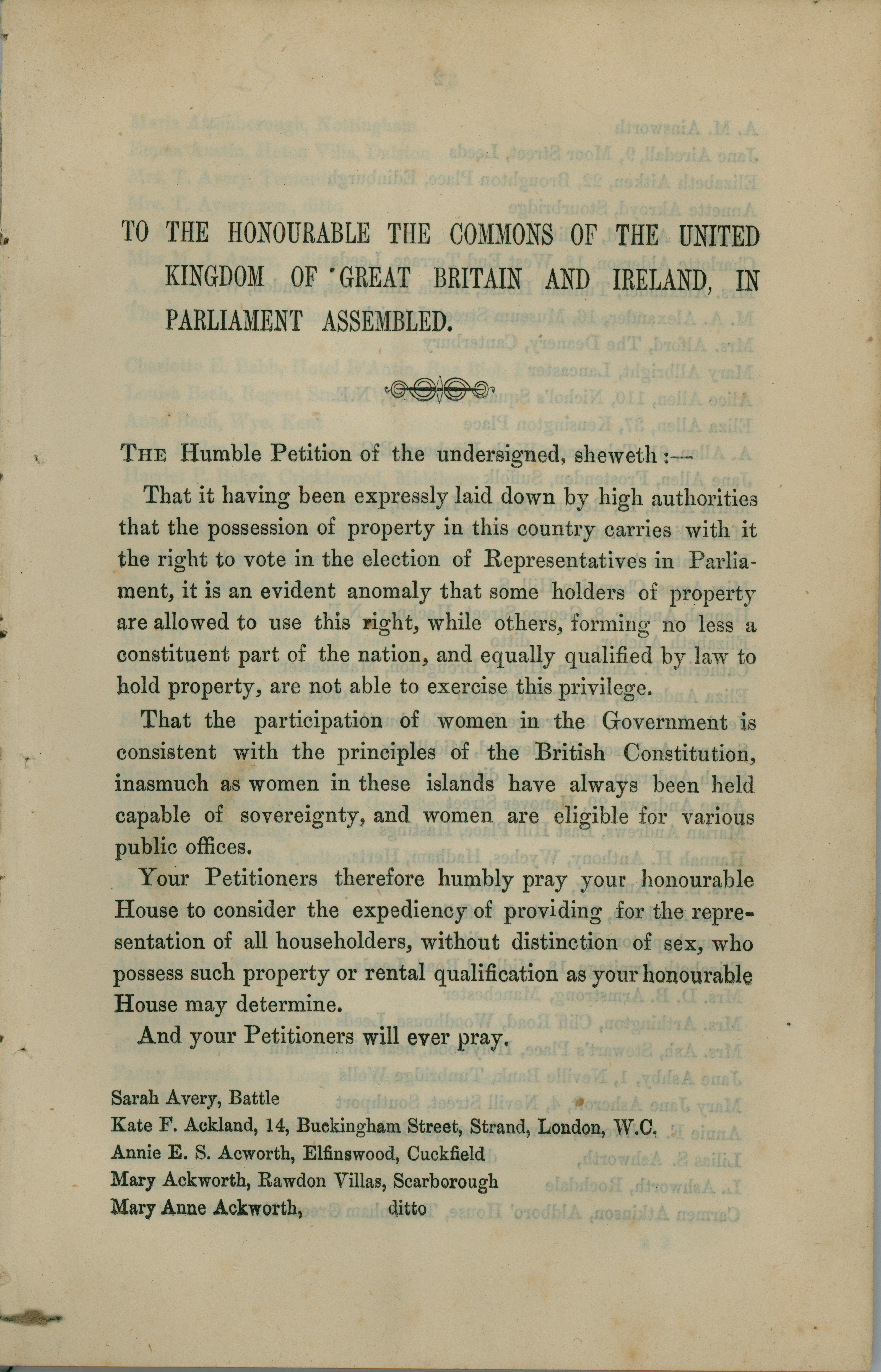

Helen and Barbara formed an informal committee with Elizabeth Garrett, Emily Davies, Bessie Rayner Parkes, Jessie Boucherett and Jane Crow to finalise the wording of the petition. They decided that the petition should be short and state as “few reasons as possible for what we want, everyone has something to say against the reasons.” The women were not asking for universal suffrage but for all householders, regardless of sex, to have the right to vote.

The petition was printed and sent out across Britain which at the time included the whole of Ireland. Further meetings were held in Elizabeth Garrett’s house and between meetings a great flurry of letter-writing took place between the women. Many of those letters are held in the Mill-Taylor collection and Barbara Bodichon’s archive in LSE Library. The letters convey a clear sense of urgency about the task they were undertaking.

The returned petitions were gathered together in Aubrey House, the home of Clementia Taylor. In less than a month, 1,499 signatures had been collected. The women pasted the signatures with their addresses onto a long scroll which was then presented to Parliament by John Stuart Mill on 7 June 1866. Before he did this, Emily Davies had the petition printed into a pamphlet copy which was sent to weekly newspapers and MPs during July. There are only two known copies in the country – one held in The Women’s Library and one at Girton College Cambridge. Luckily, Emily had the foresight to do this, as the original petition does not exist.

The members of the first Women’s Suffrage Committee knew that campaigning for the vote should be pursued. However, they could not have anticipated that the campaign would take 62 years, and about 16,000 suffrage petitions later, before women would achieve electoral parity with men in the Equal Franchise Act of 1928.

Read more

Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement: a reference guide 1866-1928, 1999

Jane Grant, In the steps of exceptional women, 2016

Posts about LSE Library explore the history of the Library, our archives and special collections.

It is very great experience.

I visited your library when it was in Whitechapel and was disappointed then that their was so little information about the early history of Suffrage movements and the important figures of the early 19th century.

men were also an important part of this . James Mill (Father of John Stuart Mill), Henry Hunt, (Orator ).who presented the first petition to Parliament in August 1832 and led the forthcoming debate. William Thompson, who wrote many books and pamphlets based on the work of Mary Godwin his first published book was in 1825..

The Peterloo Massacre in August 1819 occurred when 60,000 people gathered in Manchester to call for parliamentary reform, at that time Manchester had a population of over 100,000 people had no MPs. orator Hunt was to be the main speaker, seatd beside his coachman was Mary Fildes, organiser of the Manchester Committee of female reformers dressed all in white* , there were also 200 women reformers from Oldham, also dressed in white. * Female reform societies were springing up across the North West They had been ridiculed by cartoonists including George Cruickshank who called them sluts and whores. Thus the pure white dresses.

In the years 1901 to 1903, 67,000 women workers in the cotton industry signed petitions to parliament in support of the vote for women. By this time the textil industry in Lancashire and Cheshire was highly unionised with both men and women members.

I hope that you can find library and manuscript material to add to your collection and stop it being so London centred.