LSE often runs in the family with several generations making their way to Houghton Street. LSE Archivist Sue Donnelly writes about an unusual mother and daughter duo.

In 1919 a young Indian woman, Mithan Ardeshir Tata enrolled to study at LSE. Mithan was born in 1898 into a Parsi family in Mumbai (then known as Bombay), the daughter of Herabai and Ardeshir Tata. Herabai was born in 1879 and had married at the age of 16, giving birth to Mithan a year later.

In 1909 Herabai became a Theosophist and in 1911 while on holiday in Kashmir she met Princess Sophia Duleep Singh. Princess Sophia was active in the British suffrage movement and her influence led to both Herabai and Mithan taking up the cause of women’s votes in India. In 1915 Herabai became Honorary Secretary of the Women’s Indian Association and in 1919 Herabai and Mithan travelled to Britain to present a memorandum on the women’s franchise while the 1919 Government of India Bill was under discussion. Afterwards they travelled Britain talking to supportive suffrage societies. The immediate objective of their visit was unsuccessful – the Government of India Bill did not include women in the franchise but states were permitted to give women the vote and some did this from 1921. However, Herabai and Mithan remained in Britain for four years.

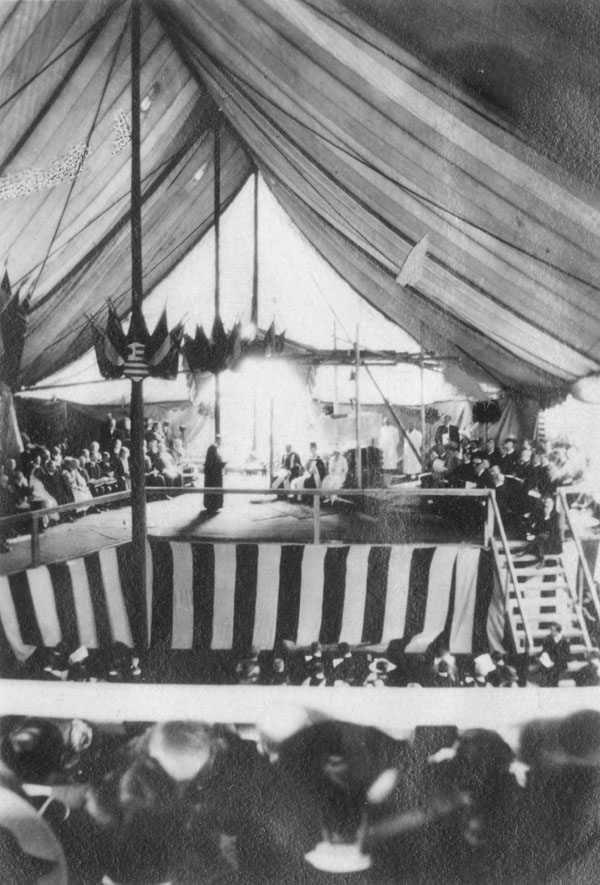

Mithan Tata had obtained a first class degree in economics from Elphinstone College, Bombay, winning the Cobden Club medal for economics. In 1919 she took up a place at LSE to work for an MSc in Economics which she obtained in 1922. She continued as an occasional student until 1923. During her time at LSE, Mithan was one of two students introduced to George V and Queen Mary at the laying of the foundation stone of the Old Building. On April 13 1920 Mithan Tata was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn, only one year after the 1919 Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act had allowed women to enter public office. She was called to the bar on 26 January 1923 less than a year after Ivy Williams, the first woman to the called to the English bar. On her return to India in 1924 Mithan practised at the Mumbai High Court and became Professor of Law at the Government Law College in Mumbai – the first woman Professor of Law in India.

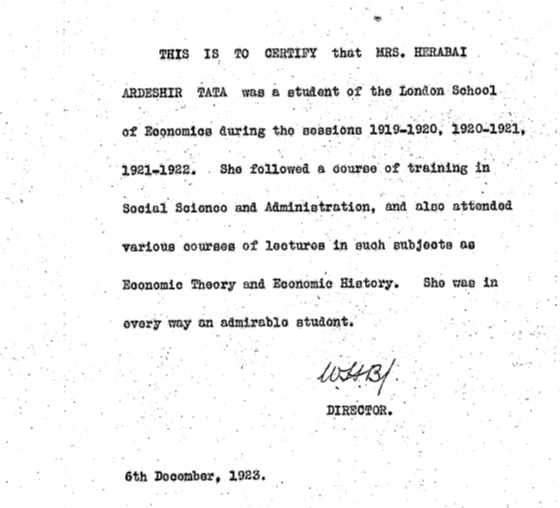

A recent discovery among the student files reveals that Herabai also registered as a student at LSE. The file indicates that between 1919 and 1922 Herabai followed the Social Science Course and took classes in economics. These included a course on the British constitution and Principles of Economics. However Herabai had not sat any exams and on her departure in 1923 she asked for a certificate to prove she had attended the courses. The certificate, signed by LSE Director, William Beveridge, was dated 6 December 1923. It concludes: “She was in every way an admirable student”.

Following their return to India, Herabai was much occupied with caring for her husband who had lost his sight in an accident. She continued her involvement in the Bombay Lady’s Association and may have been involved in relief for those affected by the 1930 flood in Bombay. I have been unable to ascertain the date of her death.

Mithan Tata married a fellow lawyer, Jamshed Sorab Lam, and was active in women’s and social organisations throughout her life. In 1947 she chaired the Women’s Committee set up for the Relief and Rehabilitation of Refugees from Pakistan. She was also involved in the All India Women’s Conference. She died in 1981.

Thanks to Dr Sumita Mukherjee (Senior Lecturer in History, University of Bristol) for additional information regarding Herabai and Mithan Tata.

Suffrage 18 is a series of posts to mark the 2018 centenary of the first votes for women, sharing stories from The Women’s Library about the campaign for women’s suffrage.

Is the School to be renamed the London School of Feminism?

Every LSE history piece seems to be about women (FYI the relevant political anniversary is not an excuse: lot of men got the vote for the first time in 1918).

I’m sure this is fun if you are a feminist, but does not add to the School’s credibility when it tries to claim that it impartially pursues knowledge rather than various political agendas ( no wonder it has taken a century to raise enough money to put up half decent buildings for the place).