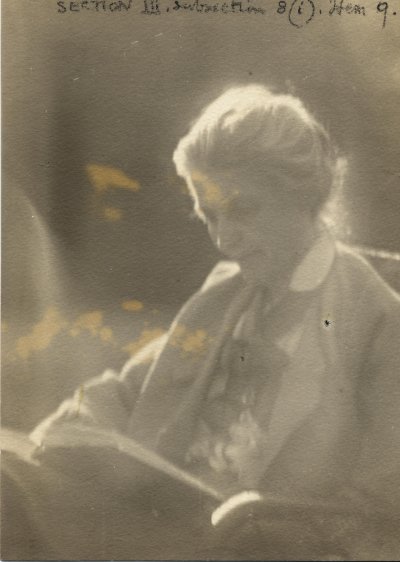

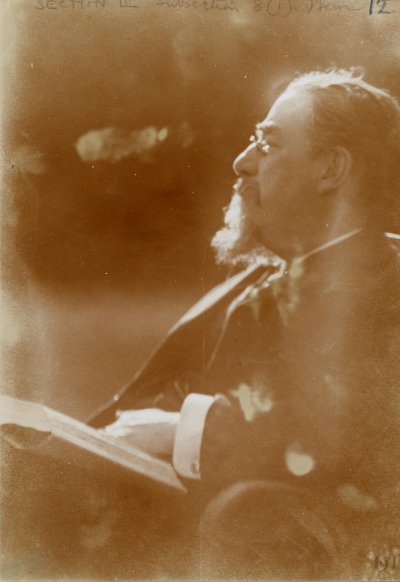

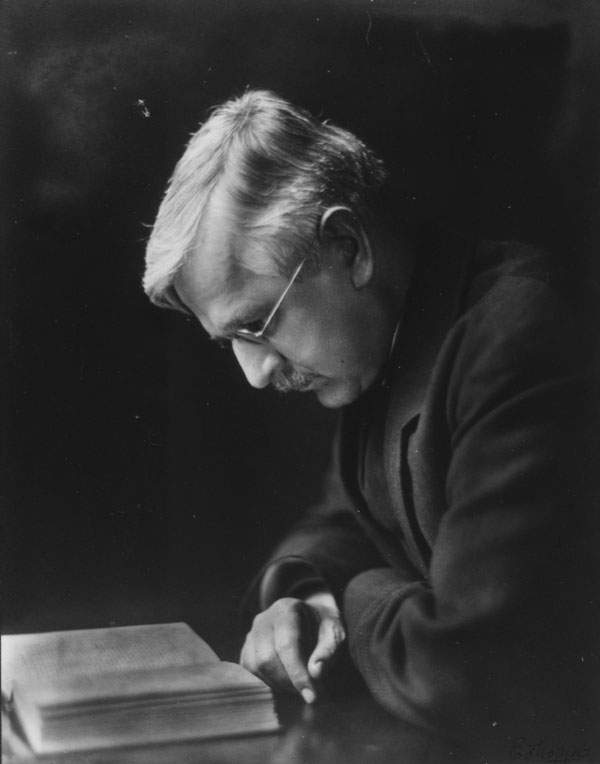

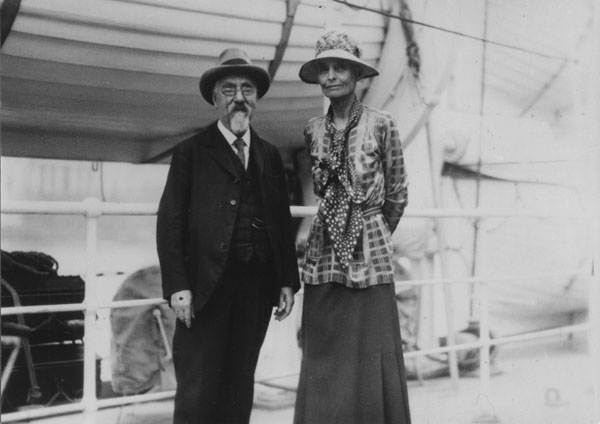

Beatrice Potter and Sidney Webb married on 23 July 1892. On their wedding anniversary, LSE Archivist Sue Donnelly looks back at their unique courtship.

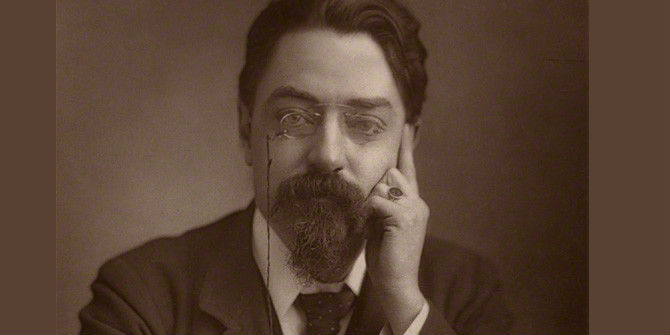

On 8 January 1890 Beatrice Potter was introduced to Sidney Webb by her cousin Margaret Harkness. Beatrice had read Fabian Essays published in 1889 telling a friend that “by far the most significant and interesting essay is the one by Sidney Webb: he has the historic sense”. The admiration was mutual – in reviewing the first volume of Charles Booth’s Life and Labour of the People in London Sidney declared that Beatrice was “the only contributor with any literary talent” At their first meeting he delivered a reading list for the British Museum Library and a few days later sent her the latest Fabian pamphlet The Worker’s Political Programme.

Beatrice and Sidney began to meet regularly and when Beatrice returned to Box House, Minchinhampton to care for her father Sidney visited for a day and recounted the story of his life. Beatrice’s initial diary comments were not complimentary, writing on 26 April 1890:

…his tiny tadpole body, unhealthy skin, cockney pronunciation, poverty, are all against him.

But Sidney was smitten and sought out Beatrice’s company and advice on his work with the Fabian Society. In May Beatrice travelled to Glasgow for a Co-operative Conference:

I in one of the two comfortable seats of the carriage with Sidney Webb squatted on a portmanteau by my side, and relays of working men friends lying at full length at my feet, discussing earnestly Trade Unions, Co-operation and Socialism.

Sidney’s attempts to discuss their friendship were rebuffed and he wrote a desperate note:

You tortured me horribly last night by your intolerable superiority. Surely an affectation of heartlessness is as objectionable as an affectation of conceit.

Still in Glasgow they agreed a compact of friendship though Beatrice stressed that the relationship was unlikely to be anything further, but throughout the summer they exchanged letters and visits. Before leaving for a holiday in Oberammergau with G Bernard Shaw, Sidney wrote:

You were so ravissante yesterday and so angel good, that I had all I could do not to say goodbye in a way which would have broken our concordat …Frankly I do not see how I can go on without you. Do not now desert me….

Beatrice remained distant until a visit to a second co-operative conference (this time in Lincoln), where Beatrice finally accepted Sidney’s devotion. She later wrote:

That evening at Devonshire House – in the twilight when we for the first time embraced – how well I remember the happiness tempered by great anxiety.

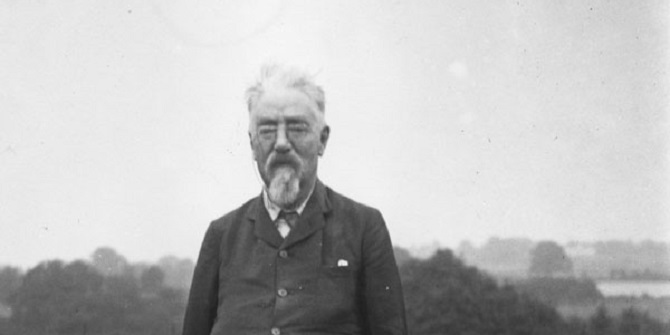

The engagement remained a secret while Beatrice’s increasingly frail father lived. Beatrice, who was his main carer, did not want to disturb his final months. He died on 1 January 1892 and Beatrice planned to tell her sisters following the funeral but the news leaked out. Beatrice was concerned that her sisters would not accept Sidney but on the whole the family decided to accept Beatrice’s choice of husband. Her sister Georgina Meinertzhagen wrote “We may not be quite kindred spirits to each other but if he makes you happy we shall certainly appreciate him in the end.” A round of dinner parties followed to introduce Sidney to Beatrice’s sisters and their husbands.

Introductions to Sidney’s family were less fraught though but Beatrice was acutely aware of her in-laws modest circumstances.

The couple spent much of the next few months apart. Sidney launched is political career as Progressive councillor for Deptford on London County Council which Beatrice continued her research into trade unions in Liverpool and Manchester. But the separation was increasingly hard and Sidney wrote:

Dear I do love you so that I am not sure that I am unconsciously constructing a new theory of the universe in which you have the centre of things. Really it is high time we were married lest I get quite absurd.

To modern ears Beatrice and Sidney’s hopes for their marriage are very high minded. In May Sidney wrote to Beatrice:

I too trust more fully – not you – but our power to live together usefully and industriously as well as happily. If 1+1 do not become eleven (which would be rather much I own) yet there is every prospect that they will come to be 3 or 4 at least – which is as much as we can expect (or more). I feel quite confident that, in our ‘domesticity’ we shall know to remember the lives of others, and work as hard as ever, and to much greater effect than we could have done alone.

But the commitment was sincere and lived out in their marriage.

Sidney organised the practical arrangements for their wedding at St Pancras Vestry Hall. If one of them lived locally for eighteen days they could obtain the marriage license for £2 9s 0d. At the end of June Beatrice ordered her wedding dress in light grey for £4. Sidney thought she would look “sweet in your new dress” though dark blue silk would have suited her better! He planned to buy a brooch as a wedding present.

Beatrice and Sidney were married at St Pancras Vestry Hall on 11.45 am on 23 July 1892. The wedding party was mainly family with Graham Wallas as best man. Beatrice’s sister, Kate Courtney thought the event rather prosaic but Beatrice’s eldest sister and her husband, Lawrencina and Robert Holt hosted a wedding breakfast at the Euston Railway Hotel. The honeymoon was spent researching Irish trade union records.

“The one thing I regret is parting with my name – I do resent that” wrote Beatrice to Sidney, and in her diary she wrote:

Exit Beatrice Potter, Enter Beatrice Webb or rather Mrs Sidney Webb for I lose alas! both names.

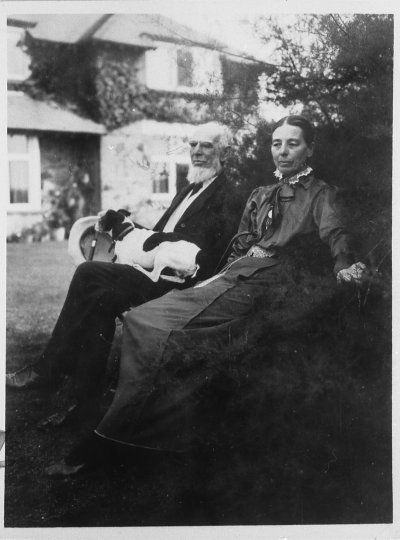

Sidney and Beatrice Webb were married for 51 years. Shortly before she died a diary entry commented:

If it were not for my beloved partner I should be glad to quit life. We have lived the life we liked and done the work we intended to do. What more can a mortal want?

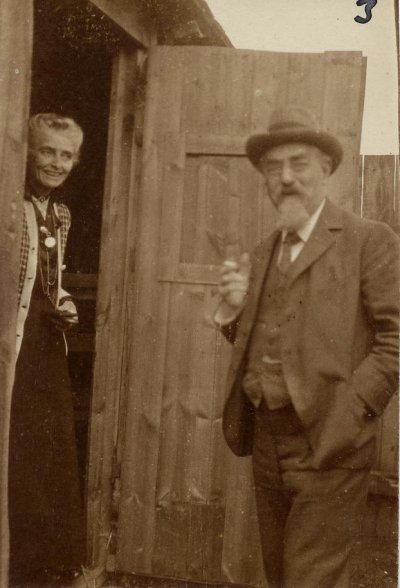

Hello – I would love to use the top photo in this Blog of Sidney and Beatrice Webb for a book I am writing on the history of the Rural Community Councils. Please would you tell me how I might gain permission to do so.

Many thanks

Nigel Curry.