In 1952 Kwame Nkrumah became Prime Minister of the Gold Coast and in 1957 the country gained its independence under the new name of Ghana. LSE Archivist, Sue Donnelly, writes about Nkrumah’s brief time at LSE.

Kwame Nkrumah was born in Nkroful on the Gold Coast in 1909. The precise date of his birth is unknown but he usually gave 21 September as his date of birth. After a Catholic mission school education Nkrumah trained as a teacher and taught in a series of schools before travelling to the USA to enrol at Lincoln College, Pennsylvania, a historically black college. He graduated in 1939 with a BA in economics and sociology and immediately enrolled in Lincoln College seminary and the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. In 1942 he obtained a Bachelor of Theology from Lincoln College and in 1943 a Masters degrees from the University of Pennsylvania. He then began work on a thesis entitled Mind and Thought in Early Society: a study in ethno-philosophy with special reference to the Akan peoples of the Gold Coast. Throughout his time in the USA Nkrumah was active in the black community and in 1944 attended the fourth Pan African Congress in New York.

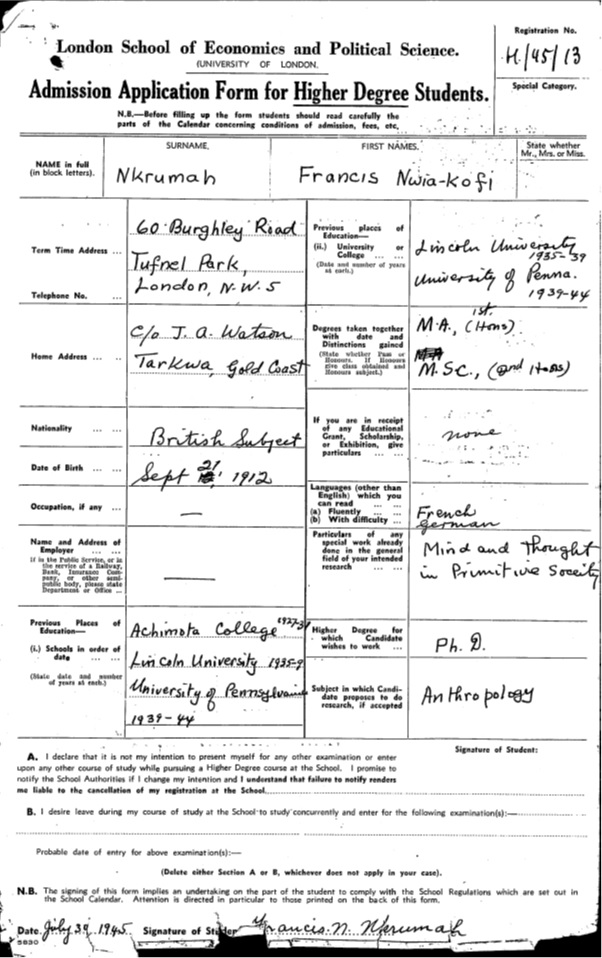

In May 1945 Nkrumah, then known as Francis Nkrumah, moved to London and in June began investigating completing his PhD at LSE. On 9 June L G Robinson, Dean of the Graduate School, invited Nkrumah to an interview with himself and the Professor Morris Ginsberg in LSE’s Second World War home at Cambridge. Robinson wrote to Ginsberg that Nkrumah wished to return to the Gold Coast, a British colony, and hoped to obtain his PhD in Britain. Initially had Nkrumah applied to finish his thesis at UCL but Professor Stanley Keeling suggested registering at LSE as his proposed thesis appeared to be closely related to sociology and anthropology.

On 13 July Morris Ginsberg wrote to Robinson: “In my view he is a person capable of producing a PhD thesis” – but he felt that Nkrumah had not been well advised and that his work did not adequately connect his philosophical thesis and the study of the Akan people. Ginsberg suggested that either Audrey Richards or Raymond Firth in the Anthropology Department would be more appropriate supervisors.

When Robinson asked Audrey Richards to see Nkrumah she was dismissive of his choice of subject but:

However I do not think he can be turned down just because it will probably be a waste of his time to do the degree since I suppose that in the free society for which we have fought one is allowed to waste one’s time as well as any other asset. Anyhow I will, of course, see him.

On 19 July 1945 her supervisor’s report said:

He seems capable of doing the PhD work, but the present title of his thesis is too vague & I think it is likely he would have to spend 6 months or so in the Gold Coast collecting first hand material as the written material on the Akan people will be insufficient probably.

Nkrumah was accepted for study with reservations. After Audrey Richards had read the thesis she confirmed that his work was up to PhD standard but felt that his anthropological training was weak and suggested that a better title would be Akan Thought Patterns in Relation to Their Social Structure. Richards also questioned whether Nkrumah had sufficient funding to undertake his studies. The title of the thesis and its relationship with anthropology was to be an ongoing issue of contention between Nkrumah and the School.

In January 1946 Robinson wrote to Harold Laski, Professor of Political Science, asking him to see Nkrumah. Nkrumah was unhappy with anthropology and wanted to start again in political science. However Audrey Richards had told Robinson that Nkrumah had done little work and was not attending lectures and seminars. It is likely that Richards and others at LSE were unaware of Nkrumah’s close involvement with the 5th Pan-African Congress held in Manchester in October 1945. The Congress is now seen as one of the significant events leading to the independence of many African countries and other attendees included Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, the Trinidadian radical George Padmore and Ras Makonnen from British Guiana. However there were few reports about its meeting in the British press.

Laski was willing to see Nkrumah who he described as “clever and plausible” but was not prepared to support a move to political thought. A small note on his file indicates that Nkrumah was unhappy with the decision. He was determined not to return to anthropology and instead expressed his wish to apply for political philosophy at UCL. On 30 January 1946 Robinson wrote to UCL:

Mr Nkrumah has in fact been in touch with us since July 1945 and was definitely registered for the PhD in Social Anthropology from the beginning of the session but things have not gone very well. His declared interest from the beginning was in a mixture of philosophy and matters that in our view came under the heading of Social Anthropology, and it was hoped that he might develop more anthropological interest and produce a thesis of the right type for that Department. These hopes however have not been realised. Mr Nkrumah is plainly not willing to concentrate on anthropological studies and we can really offer him no proper supervision in his more philosophical bent. There is, therefore, no question that this School would raise no objection if you wish to register Mr Nkrumah.

Kwame Nkrumah remained in Britain until November 1947 when he returned to the Gold Coast and immersed himself in politics and forming the Convention People’s Party campaigning for full independence from Britain. Despite the arrest of Nkrumah and other CPP leaders in 1950 the party won a landslide victory in 1951 and Nkrumah was released from prison to become Leader of Government Business. In 1952 he became Prime Minister and in 1957 Ghana achieved independence as a full member of the Commonwealth. When the Guardian’s coverage of the events of 1950-1951 described Nkrumah as a LSE graduate the Director, Sir Alexander Carr-Saunders wrote to correct their mistake.

Kwame Nkrumah was deposed whilst on a state visit to North Vietnam and China and never returned to Ghana. He settled in Guinea and died in 1972.

Browse more LSE History Blog posts from the Anthropology collection

Fascinating account. I was struck by the amount of attention the School gave to Nkrumah`s application in 1945. Would it have received similar consideration today? (I make no comment on the quality of the atention.) Have we any idea of who suggested his thesis title? Surely not the applicant himself.

Hi Gabriel and thanks for your question about Nkrumah’s application and thesis title. Blog author Sue Donnelly says, “It is clear that there was much debate about the title and subject of the thesis. The title Nkrumah was using in the USA ‘Mind and Thought in Early Society: a study in ethno-philosophy with special reference to the Akan peoples of the Gold Coast’ may well have been his own title. Nkrumah does not appear to have accepted Audrey Richard’s suggestion of ‘Akan Thought Patterns in Relation to Their Social Structure’, which would have brought the thesis clearly within the field of Social Anthropology. The application form in the blog post was completed by Nkrumah but there is no documentation about this decision.”

I am hoping to contact Dr Gabriel Newfield regarding a former acquaintance of his, the New Zealand-born surgeon Douglas Jolly. I am writing Jolly’s biography and would be very grateful to talk to someone who evidently knew and admired him

Mark Derby

Wellington NZ

Nkrumah has been a persistent person. His ideas always above par

Thank you for this detailed account. My partner is grandson to Kwame Nkrumah (he is the first son of Kwame’s first son, Francis) and this is wonderful information to fill in his years during the UK.

I love the proper documentation, about Kwame Nkrumah’s educational journey at LSE.