Women’s rights activist and former Labour Member of Parliament for Northampton North Maureen Colquhoun was elected to the House of Commons in 1974. She became the first openly gay woman to serve in Parliament after coming out a year later, write Louise Armitage and Megan Marsh. Maureen studied at LSE in the mid-late 1940s and served as a local councillor before her election as MP. Maureen lost her seat in the 1979 General Election, where the Conservative Party led by Margaret Thatcher defeated the incumbent Labour government.

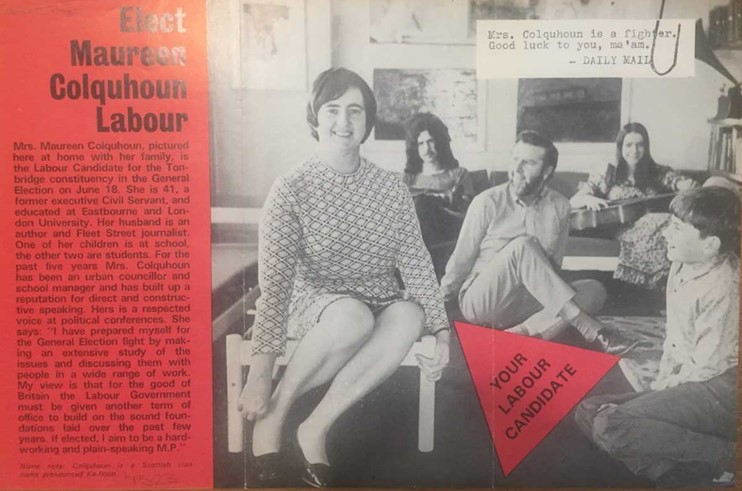

Maureen Morfydd Colquhoun, born in 1928, was raised in a politically active household in East Sussex and joined the Labour Party in her late teens. She then studied at LSE where she was awarded a degree in Economics, and later worked as a literary research assistant before unsuccessfully contesting the former parliamentary constituency of Tonbridge in the 1970 General Election.

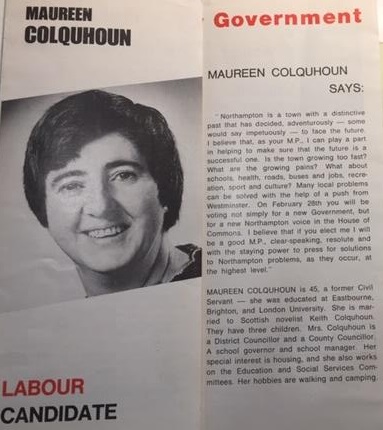

Between 1971 and 1974 Maureen was a member of West Sussex County Council and at her second attempt was elected to the House of Commons in February 1974, as representative for the newly-created Northampton North constituency. She used her maiden speech in Parliament (March 1974) to highlight the impact of the Three-Day Week on her constituents, to reinforce Labour’s manifesto commitment to addressing the pricing crisis, and spoke on achieving equality in the pensions system.

On entering Parliament, Maureen immediately emerged as a leading voice for women’s rights, working tirelessly to end discriminatory practices preventing women from active participation in public life. During a Common’s debate in March 1975, Maureen brought to the attention of the House that remarkably, after over an hour of debate, not a single woman had been called to speak on the Sex Equalities Bill. In her remarks on the Bill, Maureen challenged the discriminatory language set to appear in statute, where “he” was used throughout clauses in the text to describe persons suffering discrimination. She questioned why “s/he” wasn’t used in the text, and on setting up the Equal Opportunities Commission:

…does this mean that we are to have a commission of men and one statutory woman? Surely in this Bill above all others, it is vital that at least 50% of the commissioners should be women.

Instances such as this personified Maureen’s disappointment at the distinct lack of feminism amongst her fellow MPs, commenting in her book A Woman in the House:

There was no willingness to dismantle the patriarchal society because many of them hadn’t heard of it!

This however did not deter Maureen from inexhaustibly advocating for equal representation of women in government positions and on public bodies, and in May 1975 she introduced via a Private Member’s Bill the Balance of Sexes Bill to the House.

During its Order for Second Reading, Maureen emphasised how her idea for the bill was nothing new and instead borrowed from George Bernard Shaw (LSE co-founder), who warned the suffragettes that following enfranchisement, without adequate legislation making compulsory equal representation, little would change. She saw enacting such legislation as a key purpose of being a parliamentarian.

We in Parliament, who believe in making life better for women and that they should be the legislators as well as the makers of cups of tea, believe that our aims must be translated into laws which will be binding not merely on the present Government but on future Governments. That is what I consider I am here for.

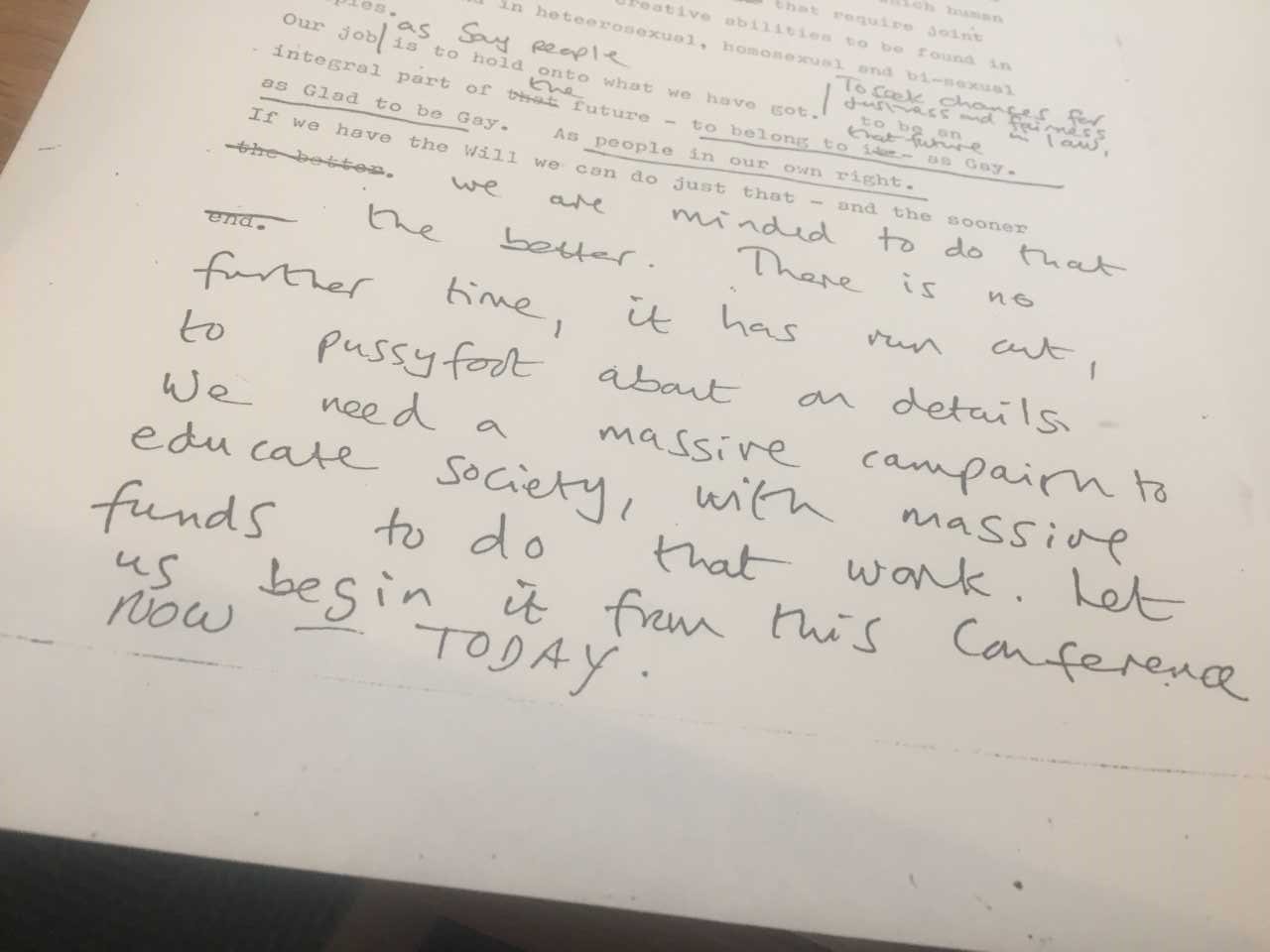

Though like many Private Member’s Bills it did not become law, Maureen’s parliamentary work drew the support of many outside Westminster, including that of Barbara “Babs” Todd, then publisher of lesbian magazine Sappho. As described in Rose Collis’ book Portraits to the Wall, Maureen and Barbara grew closer across weeks spent campaigning together on the Sex Discrimination Bill and on abortion amendments bills. Maureen commented:

By the time the House met to debate the second reading of the Balance of Sexes Bill, I knew that Babs loved me and she knew that I loved her.

It was by this point Maureen and Babs had realised their love for each other, and unwilling to maintain pretence any further, Maureen came out to her husband and children and went to live with Barbara and her daughters. Whilst she lived openly with Barbara, details of their relationship were not immediately present in the public domain, until exposed in the national press by gossip columnist Nigel Dempster in April 1976. Later writing in her book, A Woman in the House:

There was never, not once, ever any attempt to hide our relationship, and I have always sought to give us status as a couple, for I believed it to be, as I do all gay relationships, as valid and as entitled to respect as any other relationship.

The story was widely received with either silence or hostility by MPs and prompted hounding from the press, who were desperate to picture Maureen and Barbara together. Reactions amongst her constituents were more supportive, where she and Barbara campaigned and freely attended local events together.

Despite this, in March 1977 a motion was put to a constituency General Management Committee (GMC) meeting demanding Maureen be removed as candidate for Northampton North at the next General Election and six months later the GMC voted by 23-18 to deselect her. Though the GMC chair denied her deselection was a result of her sexuality, journalist Polly Toynbee captured the sentiment of many of Colquhoun’s supporters, writing under the headline:

I find it impossible to believe that they would have removed Maureen Colquhoun had she still been quietly married.

In a reactionary piece published in New Statesman, Maureen laid bare the flawed democratic practices and homophobia present throughout the local party hierarchy, and announced her intention to challenge the result of the vote.

If my opponents in Northampton North had been just and democratic, I would have won the vote at that meeting.

Maureen won her appeal in January 1978, where it was upheld by a Labour Party inquiry on procedural grounds and continued her diligent work as a constituency MP and upheld the campaign for increasing women’s rights and representation across public life.

At the 1979 General Election, Maureen lost her seat to Conservative candidate Antony Marlow and following her defeat worked as an assistant to several Labour MPs and served as an elected representative to Hackney London Borough Council from 1982 to 1990. In one of her final acts in Parliament, Maureen introduced the Protection of Prostitutes Bill to the House of Commons, where she brought 50 prostitutes to the committee room for the bill’s First Reading.

She and Barbara later moved to the Lake District, where they still remain today, and maintain an active role in local political life.

[Editor’s note: Maureen passed away on 2 February 2021.]

More on LGBTQ history

Browse our collection of blog posts about LGBTQ history at LSE.

Call for submissions

Are you researching LGBTQ history at LSE? Read our contributions policy then get in touch to submit your blog proposal.

Or are you interested in beginning a research project? Get started with LSE Library’s archive collections on LGBT history and LSE history.

2 Comments