On the 50th anniversary of the Women’s Liberation Movement in the UK Gilllian Murphy, Curator for Equality, Rights and Citizenship at LSE Library, looks at the emergence of a women’s movement during the late 1960s and early 1970s using the archives of the Women’s Library at LSE.

Wives Demand Trawler Safety Code

Following the death of 40 fishermen at sea in January 1968, Lilian Bilocca, a fishhouse worker, led a campaign in Hull for better safety aboard trawlerships. Lilian said: “If there is any ship sailing out of this dock without a full crew and without a radio operator, I shall be aboard and they will have to move me by force.”

Unusually for a woman of the time, Lilian spoke publicly about the lack of safety precautions. She, and the other wives, encountered much hostility from other women and men in the fishing community. Out of this, an Equal Rights Group formed in Hull.

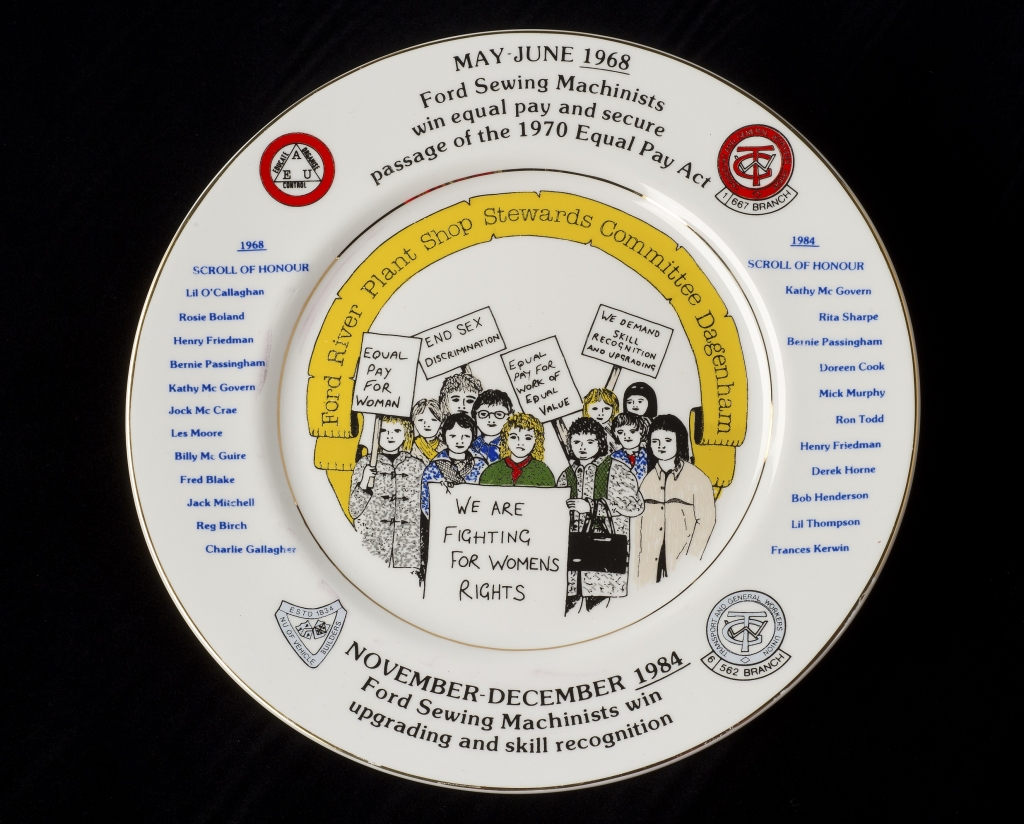

Sewing Machinists Strike at Fords

When Rose Boland and other sewing machinists at Dagenham brought Fords to a halt in June 1968, it showed what women on the left could do. The women had passed the same tests as men and wanted the same grade of pay as men but had to work on lower-paid grades. This developed into a demand for equal pay. The three weeks’ strike brought lots of publicity.

Out of the Fords strike, the National Joint Action Committee for Women’s Equal Rights was established, a trade union group for women’s equal pay and equal rights. It organised a demonstration for equal pay in May 1969.

Expansion in Higher Education

During the 1960s, higher education saw the opening of new universities and ten colleges of advanced technologies became universities. There was also global student unrest. The impact of the student movement meant that many women adopted radical politics for the first time. The student movement was attacking formal hierarchy, but in practice, women found it hard to participate equally in the very large meetings that took place. There were student sit-ins and, although women were supposed to be equal, there could be suggestions that women should do the domestic tasks, which aroused a lot of antagonism.

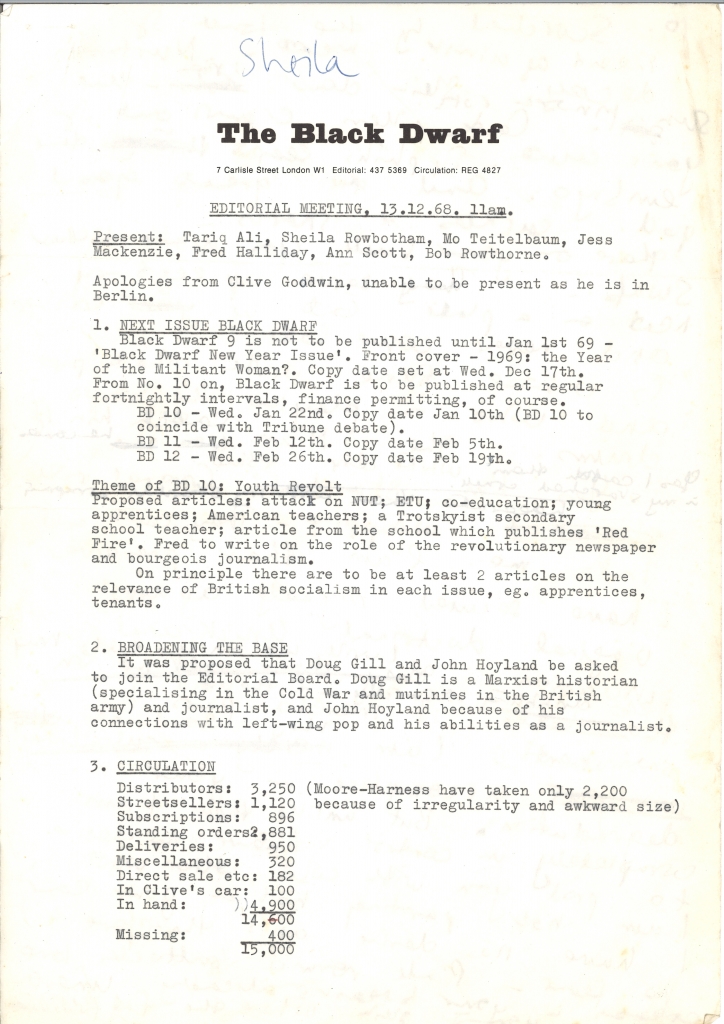

1969: Year of the Militant Woman?

The Black Dwarf, an underground, leftish newspaper, was set up by Tariq Ali, Clive Goodwin, Sheila Rowbotham and Fred Halliday (later to become lecturer and later Professor of International Politics at LSE) and others in 1968. In the following year, the January issue declared 1969 to be the Year of the Militant Woman, yet, the powerful headline was undermined by the comic and sexualised cover of a “liberated” woman. Sheila Rowbotham, editor of this issue, said her “heart sank” when she saw the layout. Articles included equal pay, birth control, child care, and Fred Halliday on “Women, Sex and the Abolition of the Family”.

Women’s Liberation Conference in Oxford, 1970

Women’s history appeared for the first time at Ruskin History Workshop in November 1969. An academic meeting on women’s history was proposed but instead it was decided to hold a more general meeting on the challenges facing women. This was planned for February 1970.

The organisers thought that perhaps 100 women would attend. In fact, nearly 500 people turned up, 400 women, 60 children and 40 men and the conference moved to the Oxford Union buildings because Ruskin College was too small. Novel for the time, fathers ran the crèche at the Oxford conference, so that women could take part.

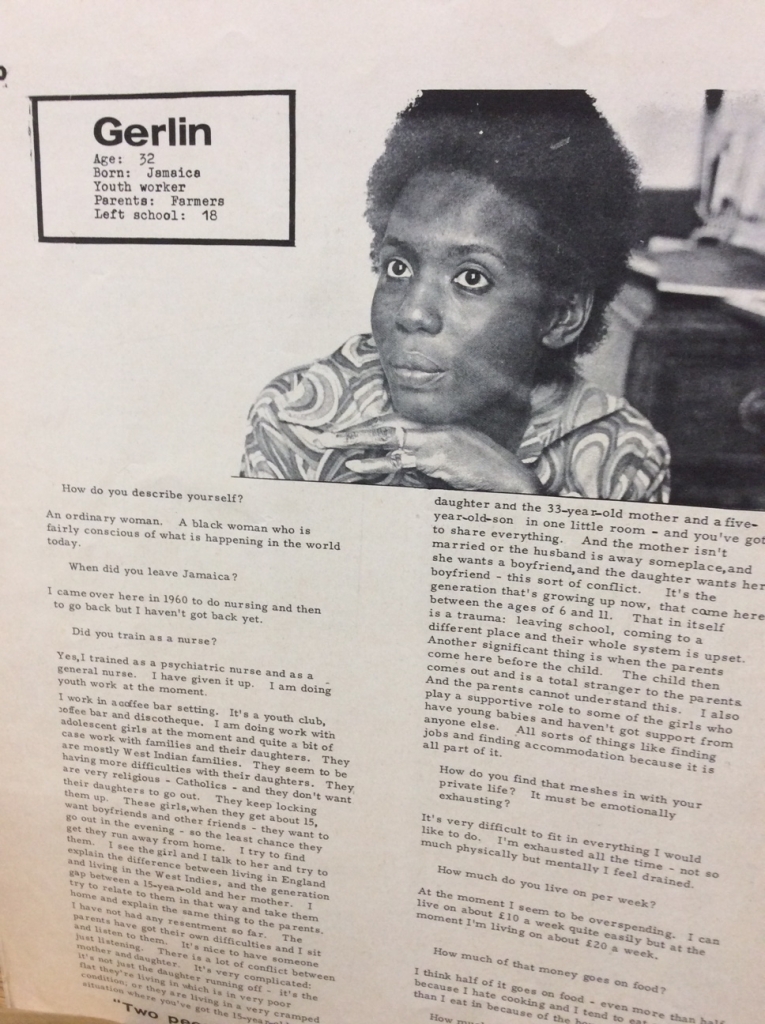

The women who came were mostly from lower middle class and working-class families but had been removed from their backgrounds by higher education. Gerlin Bean was one of the few black women who attended. When she returned home after the conference, she wanted to start a black women’s group because she said, “The problems as women are the same; the problems as black women are different. Very different.” (from an interview in Shrew, 1971)

After the Oxford conference, there was a huge growth in women’s liberation groups around the country. There were also groups that campaigned for children’s play groups, abortion rights and gay rights pressure groups. However, the movement was not cohesive or universally inclusive.

OWAAD in Brixton, 1979

For Black and Asian women, the first national conference was not Ruskin but the conference of OWAAD [Organisation of Women of African and Asian Descent] held in Brixton in March 1979. The conference was reported in Spare Rib, a now iconic women’s liberation magazine. This conference was seen as a milestone in the development of an autonomous Black women’s movement in Britain which was going to lead the struggle against specific types of oppression that affected them. “For too long the fact that as Black women we suffer triple oppression has been ignored – by male-dominated Black Groups; by white dominated women’s groups and by middle-class dominated left groups.” (from Off our Backs, January 1980).

Read more

Further information about the women’s liberation movement collection held in the Women’s Library.

Posts about LSE Library explore the history of the Library, our archives and special collections.

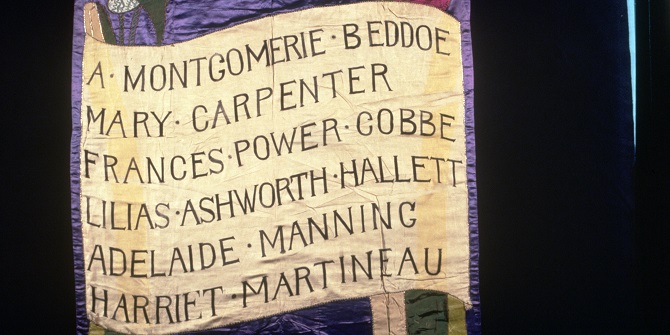

Suffrage 18 is a series of posts to mark the 2018 centenary of the first votes for women, sharing stories from The Women’s Library about the campaign for women’s suffrage.

I was a minor attendee at the Oxford Conference, but before that I was in a group called WAM – women’s action movement, which was not feminist (I was not really tuned in; got there eventually). I am trying to find out about that group, who led it, was it anti-feminist, as I came to suspect? They were going to pay me to travel to London to a conference, in about 1969. But all searches lead me to the usual Women’s lib, of which I became a member from 1971. (South Oxford Women’s Action Movement). This other group seems to have disappeared from history.

Incidentally there is, I believe, a film of the Oxford Conference, in which I speak from the floor. I wold love to find it.