To mark LSE’s 125th anniversary, the Head of the Department of Government, Professor Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey, led a team of Research Assistants to create the first ever history of the Department. Co-editor Dr Gordon Bannerman provides an introduction to “Political Science at the LSE – A History of the Department of Government, from the Webbs to COVID”.

Our research methodology encompassed interviews with numerous Department personnel, past and present, to provide a solid complement to archival material. We were faced with managing research capability amidst the societal dislocation caused by the global pandemic, with travel restrictions and library closures. The book’s title signifies how the COVID crisis had dominated the zeitgeist of the past few years.

In our volume, there is a sense of the “world we have lost” when we assess institutional, departmental, and social and economic transformation across the decades. These changes, though national in scope, appeared to us to be writ large at LSE, given the origins, ethos, and nature of the institution.

Today, perhaps inevitably, universities possess a more professional, if arguably more anodyne, approach to teaching in a competitive academic environment hedged by funding constraints, Research Excellence Frameworks, and University League Tables. There have been positive elements in this process: the increasingly market-based nature of higher education, alongside globalisation and internationalism have also contributed towards positive initiatives and outcomes based on meritocracy, inclusivity, and diversity.

It was not always thus, and our volume shows the evolution of thought, practice, and organisation of the Government Department as a microcosm of wider changes at LSE and in academia generally. Yet the Government Department has its own story to tell, its own narrative, timeline, and characters.

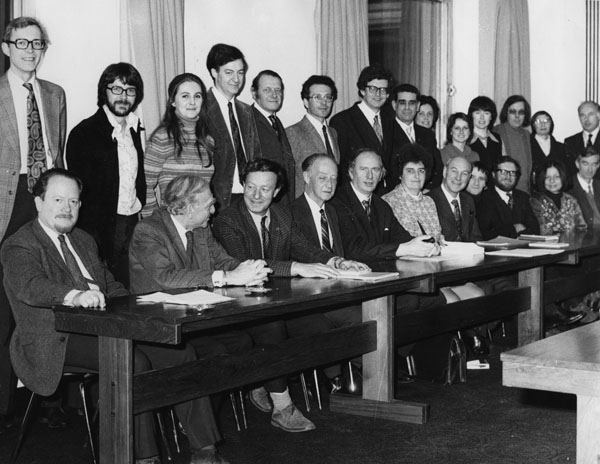

Today’s collegiate, solid, and identifiable Government Department is the product of long and uneven development, emerging from a prolonged period where an eclectic “community of scholars”, often eccentric and unorthodox, taught different components of “Public Administration” and “Political Science” but didn’t represent a “Department” in any meaningful way. This is not merely a question of nomenclature – that the “Government Department” was never referred to as such before the 1960s reflected the underlying reality that the “Department” had little tangible existence. It had few administrative and bureaucratic forms, and while we can recognise a cohort of topics that belonged in the realms of the study of government, political institutions, and political science, it was never formalised and presented in this way. Significantly, the “Department” had no “Head” before the 1960s but merely a “Convenor”, a term signifying a high degree of academic collegiality.

In contrast with today’s siloed departmental arrangements, the physical location of teaching staff was disparate, in keeping with the philosophy of a community of scholars. Even when the Department was located in the decrepit but much-beloved King’s and Lincoln’s Chambers, departmental unity was not so complete as it is in today’s new Centre Building. While the loss of co-location was regretted in some quarters, there were clearly great benefits arising from the closer proximity of department members.

“Political Science” is another misnomer. The words form part of the School’s name, yet modern Political Science, as opposed to political studies with a strong historical dimension, has only recently been taught at LSE. The tagged-on nature of the London School of Economics “and Political Science” was reflective of the term being used in a wide, generic sense, and not referencing a precise academic discipline. Aptly, on failing to find an appropriate candidate to teach Political Science in 1896, Beatrice Webb ruefully lamented that it was “a trifle difficult to teach a science which does not yet exist”. That at least was true for Britain, if not the United States.

Our history encompasses numerous events and many of the leading and influential figures in the history of LSE. In terms of the Government Department, we include a broad range of personnel, including the great figures of Harold Laski and Michael Oakeshott, successive Convenors, whose combined influences spanned nearly half a century. The identity and ethos of department and School was often contested and conflated with ideology, and while it was a cardinal principle of the founders never to allow political partisanship to influence either staff or syllabus selection, this did not prevent others from casting aspersions as to the Department’s ideological bent. As befitted a department which had Laski, a firebrand socialist, followed by the philosophical conservatism of Oakeshott, the Department has at different times been accused of being Left and Right wing.

This confusion was encapsulated in 1981 when the Wall Street Journal described the department as one of the most right-wing departments in the world, yet one whose “rosy tinge somehow refuses to wash out”. Before I first attended LSE in 1994, I often heard it spoken of as a “hotbed of communism”. Laski’s influence had something to do with this misleading reputation, which influenced both the identity of the Government Department and the School itself.

Conversely, the former Director Anthony Giddens convincingly argued that it was a great strength of LSE that it had “never been a partisan institution”. Our research has shown that despite historical connections with socialism, that LSE never became a platform or conduit for ideologues or party hacks. Pluralism was promoted not just as a political virtue but as an academic necessity. The Webbs’ view of LSE as a laboratory for dispassionate social and economic research, closely integrated with, and influencing, politics and policy development, has proved durable.

This vision arguably still serves, shed of its socialist aspirations and ambitions, as the modus operandi and strategic mission of LSE. Despite inevitable changes in form, organisation, and content, those core ideas remain vital to the LSE’s identity. Indeed, “To know the causes of things” is more than a logo – it is built into the fabric of the institution, and our volume shows that these foundational principles, represented in more rigorous research scholarship and innovative teaching practices of the Government Department, are still maintained today.

Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey & Gordon Bannerman (eds), Political Science at the LSE – A History of the Department of Government, from the Webbs to Covid is out now. Read an interview with the authors on the LSE Review of Books.