We speak to Professor Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey, Dr Gordon Bannerman and Daniel Skeffington about Political Science at the LSE: A History of the Department of Government, from the Webbs to COVID, which offers a new account of the development of LSE’s Department of Government to coincide with LSE’s 125th anniversary.

You can visit the Ubiquity Press website to purchase Political Science at the LSE or download a free, open access copy. Dr Gordon Bannerman has also provided an introduction to the book on LSE History blog.

Q&A on Political Science at the LSE: A History of the Department of Government, from the Webbs to COVID. Ubiquity Press. 2021.

Q: Why is 2021 such an apt time to reflect on the history of LSE Department of Government?

Q: Why is 2021 such an apt time to reflect on the history of LSE Department of Government?

Cheryl Schonhardt-Bailey: In an ideal world, this history of the Department would have come out in 2020 to align with LSE’s 125th anniversary. While other departments had told their histories, we had not yet done so. Hence, the motivation was quite simple in having the chance to ‘tell our story’ and be part of the celebratory atmosphere which the 125th anniversary promised the School.

But, by any reckoning, 2020 was most definitely not the ideal world! Even as the celebrations continue for our 125th anniversary, this has offered us the opportunity to reflect more closely on what holds us all together. Had we written this history in a time without COVID-19, I think that the tone and feel would have been less sombre and perhaps even a bit superficial. But writing this history in the midst of multiple lockdowns and a global pandemic has made us all more aware of the core values of LSE co-founders Beatrice and Sidney Webb, particularly the need to employ scientific knowledge for the betterment of society.

Image Credit: ‘Government Department, 1975’. Standing left to right: Peter Reddaway, Rodney Barker, Xenia Howard-Johnston, Fred Rosen, Maurice Cranston, John Charvet, Ken Minogue, Elie Kedourie, Eileen Gregory, Angela May, Gillian Farrier, Alan Beattie, Anthea Bennett, John Barnes. Seated left to right: Leslie Wolf-Phillips, Leonard Schapiro, Robert Orr, Richard Greaves, Peter Self, Elizabeth Schnadhorst, Keith Panter-Brick, Vincent Wright, Tom Nossiter, Ellen de Kadt, Ernest Thorpe. LSE Library, No Known Copyright Restrictions.

Q: When did the Department of Government officially come into being at LSE? How was political science taught at LSE before this point?

Gordon Bannerman: The Department is first cited as the Department of Government in 1962. Before then, faculty teaching courses in political science — although not organised formally in a departmental structure — taught two streams of courses under ‘Public Administration’ and ‘Political Science’. These were intended to encompass the study of government, institutions, policymaking, administration and bureaucracy. As a formal discipline, Political Science, at least how we understand it today, did not feature until quite recently. What passed for Political Science tended to focus on what we might call the ‘Whig interpretation of history’, which placed Westminster and the British political system at the centre of the political universe. That was not surprising because the nineteenth century was dominated by Whiggish ideas of history as an account of the progress of liberty, freedom, democracy and representative government.

There was an almost complete absence of quantitative methods, and research methodology was empirical, inductive and strongly rooted in historical analysis. Historical and political studies were closely linked to the older universities. Although far more empirical and relatively unconcerned with political thought and philosophy, LSE did not differ markedly in its approach to teaching political science. There was even press comment about whether LSE should drop ‘Political Science’ from its name, and most of those teaching ‘Political Science’ subjects had usually taken a first degree in History, Philosophy or Classics — an association not unique to LSE. Between 1896 and 1920 one of the early Professors, Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, taught the exact same Political Science courses and delivered the same lectures at LSE as he did at Cambridge! That is an indication of how, despite the innovations at LSE, there remained considerable convergence in personnel and course content with Oxbridge.

Image Credit: ‘Sir Halford Mackinder c1910. Director of LSE 1903-1908. IMAGELIBRARY/117’ by LSE Library, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Q: You note that particularly in the early days of LSE, the study of imperialism and the British Empire was prominent. How did this manifest in the teaching of political science at LSE?

GB: The imperial element was partly a reflection of the spirit of the age, since LSE was founded in the late Victorian afterglow of the ‘New Imperialism’ of the 1880s. There was great interest in the Empire across the political spectrum, even among socialists, and especially among the Fabians. Maintaining the Empire was often correlated with maintaining ‘Great Power’ status. Anxiety about the rise of industrial and military rivals, and the feeling that Britain as ‘first mover’ was falling behind, played a part. It also shaped LSE’s early syllabus which was peppered with vocational and business-related subjects — some have even suggested that LSE was closer to a business school than a university.

The first three LSE Directors were imperial enthusiasts who spoke and wrote regularly on the benefits and peaceful development of the colonial Empire. Indeed, William Hewins resigned as LSE Director to act as Secretary of the Tariff Commission, which promoted the idea of an imperial trading bloc. After the Boer War demonstrated deficiencies in the British military and population, we see something of a confluence of ideas surrounding social reform, national efficiency and Empire. The Fabians had a technocratic approach to Britain’s problems, indicated by their willingness to work with all political parties. Even for conservatives like Hewins, being imperial-minded was about more than the strategic possession of territories and colonial resources, framing the Empire in positive and benevolent terms — as enabling the spread of the rule of law and democratic institutions and the pursuit of individual freedom.

Domestic government and institutions were often assessed as the basis of an imperial system of governance — the two were often conflated but it was really a case of how to apply the ‘Westminster’ model of institutions and constitutional practices. The cohort of Indian students who studied courses at LSE focused on India, its governance and administration and its place within the British colonial empire. While the Directors did not overtly influence the syllabus, they did promote public lectures at LSE on imperial subjects; between 1903 and 1914, issues of imperial defence, governance, commercial policy and education were regularly debated. Ultimately, and perhaps in keeping with the times, British domestic and imperial governance always appeared, at least before 1920, to take centre-stage in Political Science. In 1919, previous Director, Halford Mackinder, delivered a lecture series at LSE on ‘The British Empire under the New Conditions of the World’. That title was clear acknowledgement of a rapidly changing world, though there remained considerable academic interest in the Empire for many years afterwards.

Q: Chapter Two focuses on the influence of two very different figures – Harold Laski and Michael Oakeshott. How did they shape the character of the Department of Government?

Daniel Skeffington: Harold Laski and Michael Oakeshott led the Department of Government collectively for more than 40 years, from Laski’s appointment to Graham Wallas Chair in Political Science in 1926 to Oakeshott’s formal retirement in 1968. Despite noted differences in style and approach, they were instrumental in building on the early achievements of Wallas in forming a university of political science at LSE.

Laski, the famously outspoken wartime professor remembered for his political oratory and Fabian socialism, created much of the early structure of the Department, transforming political science at the then business and economics-focused School into one of its most recognisable faculties, specialising in social scientific approaches to public policy and political thought. Oakeshott, his conservative successor, was met with much consternation when he took over after Laski’s untimely death in 1950, yet under his tenure the Department flourished, drawing scholars from across the world to an expanded faculty. He presided over the official creation of the Government Department in 1962, whose focus shifted from empirical political science to political history, political philosophy, European politics and the Middle East.

Laski, the famously outspoken wartime professor remembered for his political oratory and Fabian socialism, created much of the early structure of the Department, transforming political science at the then business and economics-focused School into one of its most recognisable faculties, specialising in social scientific approaches to public policy and political thought. Oakeshott, his conservative successor, was met with much consternation when he took over after Laski’s untimely death in 1950, yet under his tenure the Department flourished, drawing scholars from across the world to an expanded faculty. He presided over the official creation of the Government Department in 1962, whose focus shifted from empirical political science to political history, political philosophy, European politics and the Middle East.

Interestingly, it was Oakeshott’s scepticism of ‘political science’ as a discipline which led to the faculty being christened the ‘Department of Government’ rather than the ‘Department of Political Science’, despite the School being ‘The London School of Economics and Political Science’. He thought that the American notion of a ‘Government Department’ or ‘Political Studies’ encapsulated the subject best, similarly opposing the British Political Studies Association being named the ‘Political Science Association’, as Laski had originally envisioned it. However, while Laski and Oakeshott had highly divergent theories of political science as a discipline, both remained committed to the most important idea of a rigorous political education — the creation not of ‘followers’ but ‘thinkers’. The roles both played in shaping post-war political thought mean they remain central figures, not just in the history of political science at the LSE Department of Government, but in Britain and the wider world.

Q: Depending on the observer, LSE has been seen to occupy different points on the political spectrum throughout its history. How does the history of the Department of Government deepen our understanding of the political identity of LSE?

GB: While the Department of Government obviously has its own history, characters and development, there has often been a linkage with the School’s political identity. The forthright views of the leading figures in the Department had a lot to do with this association. Under the early tutelage of Graham Wallas, and then Laski, the collectivism which underpinned the Fabian Society was strongly identified with LSE. It was a collectivist age, and as Beatrice Webb noted, the formation of LSE was partly fuelled by a shift in Fabian tactics from ‘propaganda to education’. Yet, in succeeding post-war generations, under Oakeshott and more recent Convenors, the Department displayed more right-wing tendencies, partly on account of Oakeshott’s tendency to surround himself with like-minded individuals.

However, I feel this debate is somewhat eclipsed by the type of institution LSE has become in recent years, which has transcended political and ideological allegiances. An increasing emphasis on professionalisation and research output has meant the original ideal of a diverse ‘community of scholars’ has become obsolete. This might be considered compliance with, and assent to, capitalist enterprise and a market-based approach to education.

We conclude that while the ideological inclination of the Government Department has often influenced external perceptions of LSE (with the reputation of ‘the Red Professor’ Laski particularly apparent), neither the Department nor the LSE itself has been uniformly Left or Right. I think this is where the founding principles and ethos of the School are vital. The emphasis of the founders on disinterested research and teaching and their refusal to succumb to partisanship in appointments or course content was aligned with Sidney Webb’s stated purpose of the school: ‘the application of scientific method to public and private administration’. For him, informed policy analysis and systematic empirical and scientific study of the social sciences would lead to the rational and inevitable victory of socialist principles. However, unlike George Bernard Shaw, Webb, greatly to his credit, wasn’t prepared to sacrifice academic freedom in order to achieve that objective, and LSE was never a socialist institution.

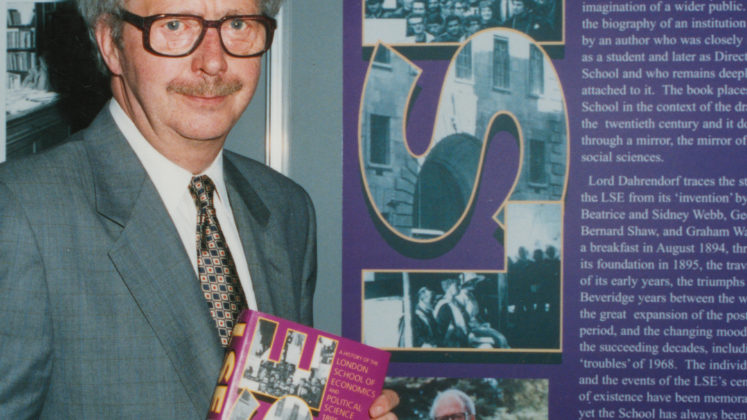

Image Credit: ‘Lord Dahrendorf, 1995’. The pre-publication launch of his book “LSE: A History of The London School of Economics and Political Science 1895-1995”. IMAGELIBRARY/513. LSE Library, No Known Copyright Restrictions

Q: Thinking back to Ralf Dahrendorf’s 1995 book A History of the London School of Economics and Political Science 1895-1995, how do you think your interpretation of the Government Department’s history stands apart from his work?

CS-B: Dahrendorf’s book commemorated LSE’s 100th anniversary. With ours doing something similar for the Government Department for LSE 125, one could say that both books were motivated by anniversary events. However, Dahrendorf’s description of the Government Department (and political science more generally at LSE) is quite different from the Department we see today. He argued that ‘modern political science’ had never taken hold at LSE, whereas that is certainly not the case now. Even in the early 1990s (when I started in the Department), one could already discern its clear presence, and these seeds have matured quite nicely, as our Conclusion illustrates. Moreover, our history, like Dahrendorf’s, aligns LSE closely with its central location in London. Yet, whereas Dahrendorf concludes his book warning that LSE is under threat from ‘the decline of London as a vibrant capital city’, our lament is that the professionalisation of higher education, and the Department as a microcosm of this, has created quite different challenges. On the whole, I think that our book complements Dahrendorf’s quite nicely, both in updating the contemporary ‘feel’ of LSE and the Department, but also (and I say this in the kindest possible way) correcting a perception of the Government Department as not ‘modern political science’.

Q: The book is a collaborative endeavour – not only in the writing, but also in drawing on interviews with LSE academic and PSS staff, students and alumni. What was your experience of collectively writing this history, especially given the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic?

CS-B: The collaboration was certainly multifaceted. The contributors included students at all levels (undergraduate, masters, doctoral), working together with Gordon (a British historian who previously studied at LSE) and me as Head of the Department. Moreover, we wanted to ensure that different perspectives were heard. Along with archival research, we included dozens of interviews with current and former academics, PSS staff, students and alumni. We wanted the history to have many voices, and I think that we have achieved that.

In terms of the challenges posed by COVID-19, they were many! First, we had only two months to conduct the in-person archival work in LSE Library before the first lockdown hit. This posed a major challenge as it made access to the historical archives impossible. Fortunately, the research that had been done, together with online research, allowed us to move forward. A major asset which allowed us to check anomalies and uncover new insights is that Sue Donnelly (former LSE Archivist) very generously found a way to download and send us a large collection of the School’s Calendars. I now have this nice collection on my home computer, which is rather useful at times!

A second challenge was that we were all working from various parts of the world — Canada, Kenya, Lebanon, Poland and different parts of the UK! Just keeping the focus and momentum going as the pandemic raged throughout the world was quite the task. Somehow, each of us managed to bring our contributions to the volume at different times, as we were each facing our own COVID-related disruptions along the way.

A third challenge was obtaining the interviews as the turmoil of COVID took hold. Here, Skype, Zoom and phone calls made the interviews possible, and in some cases were more convenient than in-person interviews. The real difficulty was that in spring 2020, many interviewees were difficult to contact, given the on-going turmoil in everyone’s lives. But the fact that so many interviewees were willing to take the time for us is a real testament to the strength of feeling that many have towards the Department and LSE more generally.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.

Harold Laski Image Credit: ‘Blue plaque erected in 1974 by Greater London Council at 5 Addison Bridge Place, West Kensington, London W14 8XP, London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham’ by Spudgun67 licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

Oakeshott Image Credit: ‘Professor Michael Oakeshott, c1960s. IMAGELIBRARY/578’ by LSE Library, No Known Copyright Restrictions.

Banner Image Credit: ‘Government Department seminar, 1981. IMAGELIBRARY/534’ by LSE Library, No Known Copyright Restrictions.