In Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars, Francesca Wade focuses on the lives of five women who lived in Mecklenburgh Square, Bloomsbury, between 1916 and 1940 – the poet Hilda Doolittle (HD), the writer Virginia Woolf , the detective novelist Dorothy L. Sayers, the classicist Jane Harrison and LSE economic historian Eileen Power. Focusing on the book’s treatment of Power as a senior LSE figure and public intellectual, LSE Archivist Sue Donnelly praises this absorbing and page-turning account of women’s lives between the wars for bringing Power and her neighbours to a wider audience.

If you are interested in Square Haunting, author Francesca Wade spoke about the book for an online LSE event hosted by LSE Library on Tuesday 29 September 2020. You can watch a video recording and read an audio transcript of the event on LSE History blog.

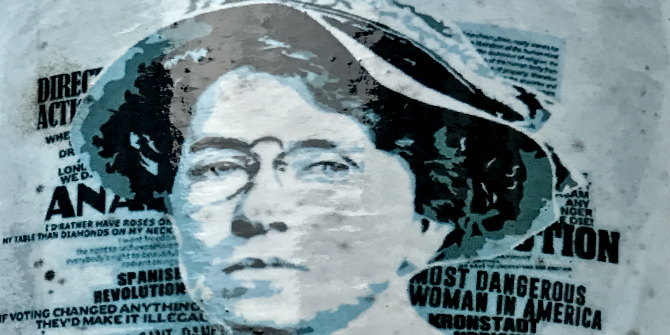

Square Haunting: Five Women, Freedom and London Between the Wars. Francesca Wade. Faber and Faber. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Mecklenburgh Square is a twenty-minute walk north from the LSE campus. Now bounded on the south and north sides by Goodenough College, in the 1920s it was an elegant Georgian square opening onto gardens on the west side. Between the wars Mecklenburgh Square, with its mix of private and lodging houses, was a base for writers, artists and intellectuals hoping to forge their careers in London. For Francesca Wade in Square Haunting, a home in Mecklenburgh Square is a space where women strive for lives of independence and ‘the right to talk, walk, and write freely, to live invigorating lives’ (344).

Square Haunting focuses on the lives of five women who lived in Mecklenburgh Square between 1916 and 1940 but does not limit itself only to the years of their residency in the square. The poet and novelist HD (Hilda Doolittle) lived in the square from February 1916 to March 1918, in a complex and painful network of personal relationships. Two years later the aspiring writer Dorothy L. Sayers moved into the same room from December 1920 to December 1921, determined to make a living from writing and plotting Whose Body?, the first Lord Peter Wimsey novel. At the far end of an academic career, the classicist Jane Harrison rented 11 Mecklenburgh Square, changing her focus from the ancient world to Russian literature and politics. The novelist and diarist Virginia Woolf and her husband Leonard moved to the square to avoid the noise of building work on Tavistock Square in August 1939, staying until bombing rendered their home, 37 Mecklenburgh Square, uninhabitable. The LSE economic historian, Eileen Power, put down the strongest roots, leasing 20 Mecklenburgh Square in January 1922 soon after her appointment at LSE and staying until her death in August 1940. These women are joined by two further significant characters – the poet Hope Mirrlees, Harrison’s partner and companion, and Harriet Vane, Sayer’s fictional mystery writer.

This is not a group biography though there are a few direct connections between the main subjects. Sayers had a tortured relationship with the Russian American writer John Cournos, a close confidant of HD during her difficult marriage to the poet, Richard Aldington. Harrison’s work on Greek archaeology is cited in Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own and the Hogarth Press published her translation of the seventeenth-century Russian autobiography Avvakum. Harrison and Power’s careers at Cambridge overlapped. Woolf eats biscuits in Power’s basement kitchen. Power and Sayers met at a party in Oxford in 1938 and discussed the difficulties of researching Palestine under Roman rule. Power was able to recommend a forthcoming book and sent a copy of Toward the Understanding of Jesus by Vladimir G Simkhovitch, writing ‘It was such a pleasure to meet you’. Strange Haunting is a reflection on the freedoms of and restrictions on the lives of women, particularly those seeking an intellectual life, and the stronger connecting theme throughout the narrative of the shared ambition of living a purposeful life. An ambition reflected in Wade’s viewing of the British Museum Reading Room application forms submitted by HD, Sayers, Power, Woolf and Mirrlees – sadly Harrison’s application does not survive.

For LSE readers the chapter on Eileen Power, LSE’s second woman Professor of Economic History, provides a glimpse into the experience of working at the School during William Beveridge’s directorship. After holding a research scholarship at LSE, funded by Charlotte Shaw, LSE governor and donor, Power had returned to Cambridge as Director of Studies at Girton College. In September 1920, funded by a travel scholarship, she set out for Egypt, India, China, Japan, Canada and North America. In India she heard the news that Cambridge would not be following Oxford University in granting women full membership of the university. She wrote to Lilian Knowles, Professor of Economic History at LSE, ‘I never felt so bitter in my life’ (209); but at the same time, she received the offer of a lectureship in economic history at the School starting in October 1921.

Power returned to London in September 1921, temporarily living in Belgravia, but in spring 1922 she moved to Mecklenburgh Square:

I am extremely jubilant at present, because I have, after much travail & tribulation, found a charming half-house in Mecklenburgh Square, looking on to an enormous garden of trees & I hope to move in at the end of term. I have found a convenient friend to share it, of the sort who is never there except on weekends, when I am often away. My idea of life is to have enormous quantities of friends but to live alone. And I do not know whether Girton or the study of medieval nunneries did more to convince me that I was not born to live in a community! (211)

The household, and Power’s freedom to work, was supported by the employment of a housekeeper.

Power shared the house with a teacher friend Marion Beard and later her sister Beryl, a pioneering children’s broadcaster at the BBC. Power is unusual amongst the book’s subjects in that she had regular employment, and in 1931 she was promoted to Professor of Economic History. Wade describes the move from the college community of Girton and Cambridge to the freedom of London and the unsegregated environment of LSE as giving Power a taste for freedom not easily relinquished.

Wade’s account of LSE and London life in the 1920s and 1930s is exuberant, busy and exciting – kitchen dances in Mecklenburgh Square, broadcasting on the radio, research into the medieval cloth industry, working with her colleague R. H. Tawney to develop joint courses on the rise of modern industry, campaigning for the League of Nations and in the 1930s working to support refugee scholars from Europe in coming to Britain. Wade argues that Power’s wide-ranging interests are reflected in her research and writing about global and social history – the lives of those who worked in fields and factories rather than ‘great men’. One can only hope that working and studying at LSE in those years was at least half as exciting as Wade makes it sound.

Alongside work, Strange Haunting also investigates its subjects’ successes and failures pursuing sustaining, satisfying and equal personal relationships while still living authentic and free lives. There were successes. Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s unconventional relationship was one which encouraged Virginia’s creativity. On 11 December 1937 Power married Munia Postan – she was 48, he was 39 and her former research assistant – having rigorously concealed their affair for several years. But in 1938 she decided not to apply for the chair in economic history at Cambridge and Postan was the successful candidate. ‘The P-P household is now commodiously furnished with two chairs!’ (324) Power returned to Cambridge when LSE was evacuated there in 1939 but it was in London that she died suddenly on 8 August 1940 following a heart attack.

Square Haunting is an absorbing and page-turning account of women’s lives between the wars. It is a strength and a weakness that all five women were writers, but in her notes Wade acknowledges four other women residents of Mecklenburgh Square who would be the fascinating subject of a book or article – I hope other writers take up the challenge. Wade also talks of the challenges of writing about individual women:

I’ve faced the difficulties of burned papers and vanished correspondences, which leave odd gaps in the record or retrospectively accord undue prominence to certain periods or friendships. (323)

As an archivist I can only agree – so often the record of a life well lived is lost after death. Eileen Power was a senior figure at LSE and a public intellectual through the 20s and 30s, yet her surviving archive is limited and a posthumous set of essays, Medieval People, was only published in 1974. Today no room or chair is named in honour of Professor Eileen Power. Francesca Wade is to be congratulated for bringing Power and her neighbours to a wider audience.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

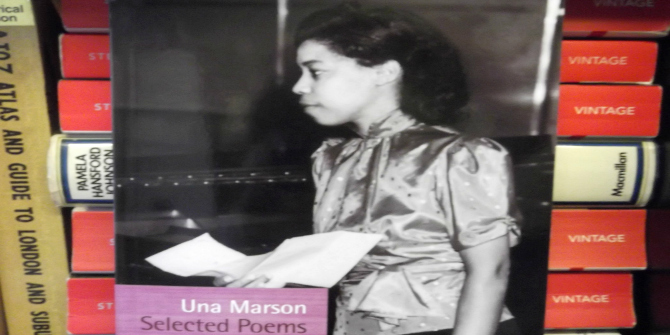

Image Credit: Eileen Power, 1922 (LSE Library No Known Copyright Restrictions).