We speak to Professor Clare Hemmings about her new book, Considering Emma Goldman: Feminist Political Ambivalence and the Imaginative Archive (Duke UP, 2018), which examines Goldman’s significance as an anarchist activist and thinker to the past and present of feminist theories and activism. Hemmings shows that the contradictions and tensions within Goldman’s approach to race, gender and sexuality speak to unresolved questions that continue to shape feminist practices and politics today.

This interview is published as part of a March 2018 endeavour, ‘A Month of Our Own: Amplifying Women’s Voices on LSE Review of Books’. If you are interested in this book, you can read the LSE RB review of it here.

Q: Could you introduce Emma Goldman to readers?

Q: Could you introduce Emma Goldman to readers?

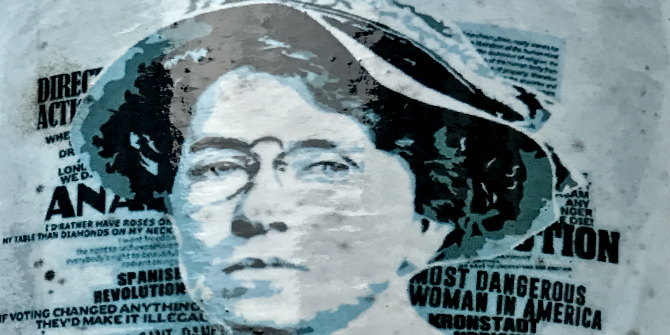

Emma Goldman (1869-1940) was an extraordinary character, an anarchist activist. She was born in what we would now call Russia, and moved to the United States when she was around 17/18 years old. Her life spanned that particular period of global transformation when socialist and anarchist movements were at their heights post-World War I.

Goldman was radicalised in the US through the Haymarket Martyrs, who were anarchists falsely accused of killing police officers. From that moment, she was committed to anarchist causes: challenging authority, strengthening labour resistance and working towards the idea of anarchist revolution. In the US in the late-1890s and early-1900s, many anarchists like Goldman genuinely thought revolution was imminent and were trying to work out the kind of life that would follow afterwards. At the time, the circulation of anarchist journals in the US was much higher than any other socialist journal. 4000-5000 people would routinely turn up to hear her speak, such that she would have to be put on a cart and driven through the streets repeating her words.

Goldman was exiled and moved multiple times during her lifetime. She was deported from the USA to Russia in 1919, due to Edgar Hoover’s obsession with her as part of the emerging FBI. Goldman was disappointed by the Bolshevik revolution and was forced to leave without papers, moving to Europe where she lived for most of the rest of her life.

Q: What drew you to explore Goldman within your work?

One of the things that is very particular about Goldman, though not unique to her, was her interest, as an anarchist, in the centrality of what she described as sexual freedom to the idea of revolution. On the one hand, she was a mainstream anarchist: she was very popular, there were lots of press reports about her. On the other, she absolutely believed that women’s sexual oppression was central to why women and men did not develop as revolutionary political subjects. For her, one of the reasons why there hadn’t already been a revolution was because of women’s labour: going along with the easy route to prevent poverty and violence in their lives, women’s dependence on men made of them, as she put it, ‘parasitical subjects’. For Goldman, the social institution of marriage is one of the key lynchpins through which capitalism and nationalism work. She viewed women as uniquely positioned as femininity reproduces capitalist dependencies, but also places women at the centre of revolutionary feeling due to their reproductive and unpaid domestic labour in the private sphere. So any account of revolution that doesn’t think you need to get rid of marriage and emancipate women sexually and emotionally cannot work. For her, you can’t wait until after revolution, because without women, there will be no revolution in any real way.

These themes of sexual freedom, the critique of femininity as both complicit but also the site of transformation and her commitments to anti-nationalism and transnational social movements are the key areas of Goldman’s thought that I’ve been interested in through my own work, because they resonate so strongly with contemporary problems within feminist activism and theory. For me, feminism still has yet to grapple adequately with the problem of femininity, and within my field of queer theory, we have yet to contend with the idea of sexual freedom as opposed to sexual rights. And in critical race studies, what we mean by race and racism as distinct from class and labour is still very much in process.

So these are three sites of political struggle contemporarily – very lithe, very present, but also very unresolved. There are a lot of ways in which Goldman is also ambivalent about these issues that can help us think about what it means for us to have not resolved them in the present.

Q: Ambivalence is in the title of the book. Could you talk more about how it is key to thinking not only about Goldman, but also about the oft-disavowed ‘history of uncertainty’ within feminism?

This is the second book in which I try to think about the histories of how we talk about the past and present of feminist theory and action. One of the things that has always seemed unsatisfactory is that we often talk about histories of feminist thought as though they were both teleological and resolved. As though questions of equality have got straightforwardly better for women, rather than going in cycles of moments of hope and of desperation. I have therefore been wary of telling a story of the past that would somehow clean it up as a way of highlighting how we’ve got to where we’ve come. If you do look at a figure from the past, why do we presume that you can’t tell a complex story that pulls through a range of different threads, that highlights contests over meaning that they may represent, embody, allow to survive and thrive?

I was very interested in how the secondary critical material on Goldman is keen to either reclaim her as a fabulous heroine we should emulate or else to position her as of her time, so that if you are disappointed with something she said or did, then you can leave that attached to her, rather than thinking of what that might mean for you. There’s a lot of work that states: ‘well, she’s a bit mean to women, so we need to be careful about claiming her for feminism.’ Or her sexual freedom is dependent on a very strong attachment to men that is her downfall. Or she’s interested in questions of nationalism and militarism, but not so great or sustained on race and racism. It’s as though our own contemporary preoccupations should have been anticipated by her and taken on board.

We therefore tend not to focus on what we might learn from what Goldman hasn’t resolved, or to see what’s tricky to read in her work as methodologically important for providing a way of thinking through how we also struggle with these questions. We expect her to carry our disappointment, rage and betrayal, or otherwise pop up shiny and clean and representative of our certainties in our own image, which prevents us from really grappling with the difficulties that feminists face about how they interpret the world and where they want to intervene in it.

I’m therefore interested, both academically and politically, in trying to tease out sets of procedures, practices and methods for starting from the presumption that things have not been resolved, and that ambivalence is likely to characterise struggle over political meaning more than certainty. What do you gain rather than lose when you start from ambivalence? What we lose is that marvellous creative opportunity of inhabiting not knowing.

Q: It’s a small example, but in the book you take that often-criticised phrase of ‘I’m not a feminist, but…’ and you open up a space for acknowledging its ambivalence.

Yes, staying with the difficulty. I identify very strongly as a feminist so I am likely to be on the side that hears that as a disappointment. If you were not a feminist and you heard that, you might be relieved. But when you listen to the grammar of it, it’s an ambivalent phrase. In other words, it could take you away from the feminism part, but it could return you to it in a way that highlights uncertainty about its precepts – it’s that hesitation of the political return that I’m interested in.

I’m also interested in it because a result of problematic certainties in feminist theories and politics is that it is easy to be overly concerned by how or to what extent people identify as feminist, rather than the work they do to ameliorate sexual and gendered inequalities. And that’s why I was interested in Goldman. Because she doesn’t identify as a feminist, but is an important figure for feminist histories exploring who and under what circumstances people have intervened in gendered and sexual politics. But I don’t resist people being feminist!

Q: Ambivalence also allows for disagreement and antagonism. LSE are focusing this year on the suffrage movement, but Goldman was very critical of their version of women’s emancipation.

Goldman was no fan of equality agendas of any kind, because her position was anti-authoritarian. She was also critical of early-twentieth-century reformist movements, liberalism in general, and certainly of suffrage. Because she saw all of them, and indeed any single-issue politics, as wanting to access the status quo through having a piece of the pie. For her, there was no value in having the vote because all it would allow you to do is feel like you had freedom to participate in democratic life, when the social structures that allow this are so hierarchical and authoritarian that they need to be challenged and transformed root and branch. So it’s not so surprising that she was anti-suffrage. What’s interesting is how vitriolic she was about suffrage particularly.

Q: Goldman was often in exile, a migrant and involved in transnational anarchist movements. But within the book, you also talk about her problematic approach to race and racism, and ensuing tussles over her intersectional importance.

One of the reasons that people find Goldman extremely attractive today is her perceived position as an intersectional thinker before her time. There is no question that Goldman linked sexual freedom with nationalism and militarism, had relationships of high intensity with men and women and covered thousands of miles within her lifetime. Yet, especially in the late-1990s and early-2000s, this is also vital for claiming her as an immensely important figure without questioning race and racism. Goldman talks about these in ways that are complicated, difficult, racist at points, transformative at others … Faced with the anxiety this produces, any grappling with race and racism in the critical archive of her work has been all but entirely displaced. Attention on her intersectionality, her migration, her anti-nationalism and her Jewishness can become one mechanism through which her extremely ambivalent, often egregious but sometimes important, attention to race becomes obscured. So instead of thinking intersectionally about how race and class and sexuality come together in Goldman, I became interested in whether the desire for her to be an intersectional heroine actually allows us to stop thinking about race. There can be a relief in citing intersectionality as a way of not having to do the difficult, messy work of engaging with race and racism as well as their difference and similarity to questions of labour and class. So I think that’s interesting: that questions of intersectionality are not always a way of dealing with race; they can be a way of deflecting it.

What we might therefore miss with Goldman are her ambivalent engagements with race and racism. For instance, she does begin to articulate a theory of sexual freedom beyond marriage and borders that challenges the race basis of familial attachments as they are linked to national attachments: a particular way of linking sexual and race politics. I like her idea that if we move past the family, we can think creatively of generating connections across borders. We might agree or disagree, but it shows that Goldman does address race, but perhaps not in ways we might like.

Q: On sexual freedom, at the end of the book, you include a partly imagined, at times feverishly intense correspondence between Goldman and one of her lovers and confidants, Almeda Sperry. Could you talk about the decision to include this chapter and the process of writing it?

We’ve got 60+ of Sperry’s letters, which were only discovered a few decades back, and which chart her desire for Goldman, her fervour and (later) violent attachment, as well as her precarious location as an activist, unionist, sex worker and alcoholic living in a small East coast town. We do not have Goldman’s replies. I thought about what it might mean to do interdisciplinary academic work that takes seriously the possibility that while we do not have Goldman’s responses, we could imagine them through the way that Sperry refers to letters she has received.

The letters we have are this mess, so one of the things that I did was order them. Sperry was an activist, a sex worker and an anarchist in a particular period whose own archive has been lost because it’s just this collection of letters. They have been reproduced in gay and lesbian anthologies before as examples of lesbian desire. But all the obsessive, violent stuff doesn’t make it into the reproductions; it’s only the nice ones that do.

I thought: what happens if you read the whole correspondence to make her more integral? And also, what if I use my vision of Goldman’s letters as part of this chapter to foreground the question of what you desire in your object? In this sense, I was positioning myself as a third-party voyeur of their relationship. They are my reading of Goldman’s likely letters, an imagined correspondence. This isn’t just about sexual identity, but about eroticism, about sexual freedom that doesn’t have to necessarily end up as happily-ever-after. And as a means to understand their exchange as generating possibilities in the world that otherwise aren’t registered: labour, their struggles, sickness are all key to this. The process was a way of trying to highlight what it might look like to cherish a correspondence that may not do what you might like it to.

Q: There’s one letter in which Sperry uses a racist slur and when you write back as Goldman, you imagine her speaking back to this. That was striking in light of the themes the book explores.

I didn’t include this letter because I wanted people to like Sperry and so expunged this part of her language, in much the same way as other critics have done with Goldman, as discussed earlier. But I caught myself in this process, too, and so used Sperry’s inclusion of a racial slur as a way of thinking through how Goldman might have responded. While she herself also relied on racist stereotypes at times, she did see racism as a problem of oppression, and consistently spoke out against violence directed towards the vulnerable in all contexts. So I imagined her both noting and challenging Sperry on the one hand, but not making it a central feature of their exchange on the other. It doesn’t interrupt their communication, in other words, in ways that use of anti-working-class representation might have. Class trumped race for her, and I wanted to find a way of representing that ambivalence in Goldman. So I left that in as a way of framing the encounter, showing where Goldman might have engaged without holding a line.

Q: Did the process of writing this imagined correspondence change your approach to the book or to Goldman herself?

It made me more sympathetic to her. It changed my sense of what her views on sexual freedom were: by the end, I was absolutely persuaded that it would be an outrage to think about sexual freedom only in terms of the question of whether Goldman was too interested in men. For us to be able to imagine how it would be to respond to those letters, to have this intense writing and sex with Sperry while being constantly incarcerated, poor, ill, and then to make a judgement about whether she acted appropriately enough to suit us … Because she’s so famous now, one forgets that she’s articulating things that didn’t even have a language and with such risks attached to doing so. So, I thought: she’s pretty incredible, and I want to be able to do justice to her in all her complexity.

This interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image One Credit: (Loz Pycock CC BY SA 2.0).

Image Two Credit: (Wikimedia Commons CC BY 2.0).

2 Comments